Killing standards for tailpipe emissions in cars and trucks may seem easy, but you can only do it if you can show there's an actual reason for it. A stroke of a pen won't do the job.Kevin Drum

Presidential candidates often talk about what they’d do on “Day One.” This is dumb. There’s very little of any substance that presidents can do by executive order on their first day. Take Donald Trump. On his first day he signed an order aimed at “minimizing the economic burden” of Obamacare. It was meaningless. Two days later he pulled out of the TPP trade deal. This was not meaningless at all, but Trump could only do it because we were never part of TPP in the first place.

A better question to ask candidates is: What executive actions would you begin on Day One? You see, it’s not just a stroke of a pen for most things. Back in 1946, after FDR had vastly expanded the federal government with an alphabet soup of new agencies, Congress passed the Administrative Procedures Act. The basic idea behind the APA was this: after the New Deal and World War II it was obvious that big government was here to stay, and this meant that only executive agencies had the manpower and knowledge to keep rules and regulations up to date in a world that changed relentlessly. But if that was the case, then Congress wanted to make sure that presidents couldn’t just arbitrarily change those rules whenever they felt like it. So the APA put in place specific procedures that had to be followed. In particular, agencies were not allowed to change rules “arbitrarily or capriciously.”

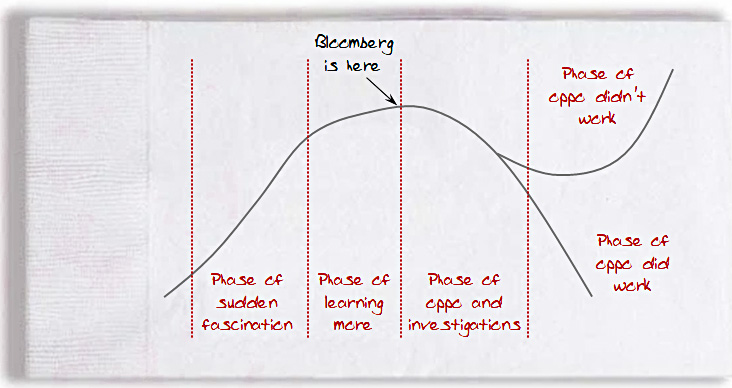

Long story short, this means that most regulations of any real importance take 3-4 years to get through the stages of research, drafting, public comment, and publication of the final text. If you want to make sure that something takes effect during a term of office, you’d better start the wheels turning within your first year. President Obama’s new fuel economy standards, for example, were announced in May 2009 but weren’t finalized until August 2012. Lawsuits can drag things out even further. Obama announced the Clean Power Plan in June 2014, but it was still waiting for a ruling in the DC Circuit Court in 2017, at which time Trump’s EPA asked for and received a stay pending its own review. At that point it was effectively dead. Obama had waited too long to get it solidly in place.

Over at the Atlantic, Robinson Meyer has a good piece about how this all works—or doesn’t. When Trump took office, he immediately decided to weaken Obama’s fuel economy standards. The problem was that those standards had been finalized years before and were not the target of lawsuits. The only way to change them was to go through the entire regulatory process as defined by the APA.

Luckily for us, Trump is an idiot. Or, more precisely, he likes to hire idiots who are eager to feed him happy talk about how easy it will be to do what he wants. As a result, no one bothered to perform the kind of rigorous analysis that’s required to finalize this kind of thing:

To change a federal rule, the executive branch must do its homework and publish an economic study arguing why the update is necessary. But Trump’s official justification for SAFE is honeycombed with errors. The most dramatic is that NHTSA’s model mixed up supply and demand: The agency calculated that as cars got more expensive, millions more people would drive them, and the number of traffic accidents would increase, my reporting shows. This error—later dubbed the “phantom vehicles” problem—accounted for the majority of incorrect costs in the SAFE study that the Trump administration released in 2018….Once this and other major mistakes are fixed, all of SAFE’s safety benefits vanish, according to a recent peer-reviewed analysis in Science.

….The errors they and other independent analysts found are staggering in their scale. At one point, the NHTSA team forgot to divide by four. Elsewhere, it used bad data, claiming that, in the future, there will be fewer of certain types of fuel-saving engines than there are on the road already. But these errors pale in comparison to NHTSA’s insertion of millions of “phantom vehicles” onto American roads.

….Last month, [Tom] Carper, the Democratic senator from Delaware, alleged that a new version of the NHTSA study admits that SAFE will impose $34 billion of costs on the American economy. (NHTSA had once promised $230 billion in net benefits.) The new study also admits that SAFE will cost consumers an extra $1,400 at the pump on average—and that SAFE will not save hundreds of lives a year, as it once claimed, Carper said.

If, in fact, the Trump administration performed a shoddy analysis that, when corrected, shows that his proposal has no actual benefits, it’s unlikely to pass judicial review. That pesky Administrative Procedures Act doesn’t allow Trump to arbitrarily change published regulations just because he wants to thumb his nose at Obama. But that’s what he did, and his appointees were happy to whomp up a draft proposal that used made-up numbers to justify whatever the boss wanted. Apparently they didn’t realize that this isn’t allowed.

Trump’s rules are in limbo right now. It’s possible that some kind of compromise will be reached that both California and the big carmakers will accept. If that happens, and there are no lawsuits, then judicial review won’t matter. If not, it will end up in court. And it will probably lose.