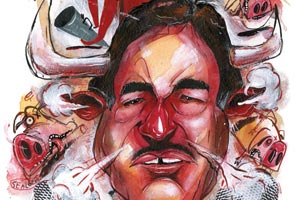

Illustration: Rick Sealock

“I’m battered. I’m dead.” Oliver Stone, the provocative, prolific, and now-mustachioed film director, is tired and eating a late breakfast at a Washington, DC, hotel. Stone is a busy man. He’s in town frenetically promoting South of the Border, his documentary that sympathetically examines Hugo Chavez, Venezuela’s socialist president, and seven other left-of-center South American leaders. Stone, 63, has also recently finished Wall Street: Money Never Sleep, the sequel to his 1987 film that encapsulated the financial excesses of that era in one character and his mantra: Gordon “Greed is Good” Gekko. And he’s wrapping up a 10-part documentary for Showtime, The Secret History of the United States. As Stone, a mash-up of Hitchcock and Chomsky, is about to talk to a group of well-dressed Georgetown ladies about South American populism, he chats with me about his latest works:

Mother Jones: When did you first say to yourself, Gordon Gekko must return?

Oliver Stone: [Laughs.] I didn’t. Gekko was like Scarface‘s Tony Montana, proverbially dead. I thought ’87 marked the end of an era. I was not in touch with Wall Street after the movie because I was burned out on it. I thought there’d be a recognition that the greed, the ugliness, was enough. But in 2006, 20th Century Fox asked me to revisit it. I said, “No, I don’t want to do this. How do you glorify a bunch of pigs?” They came back to me after the crash in early 2009 with a decent script. But it was all about hedge funds, not the right tone. But I said ,”Yeah, I’m very interested,” and went to work with [writer] Allan Loeb. We went to Wall Street quite a bit and talked to everybody who would talk to us, One of the most interesting of the interviews was with Eliot Spitzer. He said, “Check out the AIG-Goldman connection.” He hinted that Goldman might be shorting the market.

MJ: In the original Wall Street, the villain was a corporate raider who bought companies broke them up, sold off the pieces, and people were thrown out of work—it was very concrete. In the new one, who’s the villain, and how do you make the shenanigans—derivative and algorithms—concrete?

OS: It’s a different story. The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act unified investment banks and deposit banks. It really is a disaster. In the movie, you’ll see the bankers are playing every end. They’re bookies. They play long and short—like any good gambler. Their profits are going to come from trading for themselves. What interest do they have in society? The big theme is that the real banks have disappeared. There are no banks. That’s not a drama in itself. It’s the background.

MJ: So what’s the essence of the deal?

OS: Gekko comes out of prison. He’s got nothing. We see a game that involves him—Frank Langella and Josh Brolin and the young Shia LaBeouf. Shia’s character is a good kid, trying to do things the right way traditionally, by using an investment bank for the right reasons: building an alternative energy company. He tries to use the banking system—like I’m trying to use the film business—to make things better. And he runs up against the essential roadblock, which is: Is the bank interested in itself, or is the bank interested in society? Gekko plays an ambiguous role in this—because Shia uses Gekko to try to break the lock on the bank. But Gekko’s using the kid to try to make his money back. [Laughs.] It’s more complex than the original. There are no working-class people except for Susan Sarandon, who’s Shia’s mother. Interesting character: She’s an ex-nurse who became a realtor and is trying to make a quick buck by rolling over houses. She’s the only working-class person you see who gets hurt.

MJ: Did you find it hard to make this abstract stuff linear and cinematic?

OS: What you see is not a bunch of individual guys running around and making money, although there are characters like that. You see banks, you see the Federal Reserve Board. You didn’t see that in the original movie because Gekko never got so high. You see that the essence of our system is pretty fragile. But it comes back essentially to the question: Are you going to be a human being, or are you going to be a pig? [Laughs.] I’m putting it into simple terms.

MJ: In the first movie, the mantra was, “Greed is good.” Is there a tagline for this one?

OS: “More.”

MJ: Donald Trump had a part in this movie—though I hear that scene was edited out. What was it like to direct him?

OS: He couldn’t believe I asked him to do retakes. [Laughs.] I said, “Donald, you know, I want this and this,” and he said, “Why?” He’s not exactly a trained actor. Because he’s used to telling directors what to do, it’s not that easy for him to be told what to do. But we enjoyed each other,

MJ: After the movie W came out, did you hear from any of the real-life characters about how you had portrayed them in the film?

OS: No, but Bill Clinton told me that he gave a copy of it to Bush [Laughs]. Clinton liked the movie. He knows the father, he knows the son. He basically said, “I think you got it”—the father-son connection. And I heard from a friend who was at a dinner with Nancy Reagan that she loved the movie.

MJ: Having directed Platoon and other Vietnam movies, have you considered a film on the Afghanistan or Iraq wars?

OS: All the war movies are always about our soldiers—you never see any Iraqis or Afghans. There’s a flaw in that. I don’t like this new tendency is to glorify our soldiers and say, “Well, they may be in the wrong war, but they’re wonderful men, they’re honorable men, blah blah blah.” We’ve heard this to death. I mean, Hurt Locker shows at least the tensions that the men go through. But still there’s not [an Iraqi in it.] Green Zone was one of the more sensitive films because it really summed up some of the issues that showed the Iraqi side better. I did three movies on Vietnam, one on El Salvador. You have to be inspired to make a movie. I guess it’s not inspiring. Also there are veterans who actually were [in Iraq and Afghanistan] and they can tell this story.

MJ: We live in an era of hyper-media. There’s so much information coming at people. Can you cut through that clutter with big feature films?

OS: That’s a valid question, and there’s a lot of stuff out there littering the landscape. I’m working on The Secret History of the United States. Why did I want to do it? I want my children to have access to something that looks beyond what I call the tyranny of now. You read the paper, everyone talks about that thing [in the news] that day, and all the subconscious really important stuff that’s going on is being neglected. The beauty of history is that historians have the ability to find patterns, the big picture. When you make a movie, you try to find that. I’m doing in the cinema what historians try to do in their own media.

MJ: Do you think a movie can punch through?

OS: If you get it right. Avatar worked for large audiences and inspired people. It is harder. But you have to go deeper.