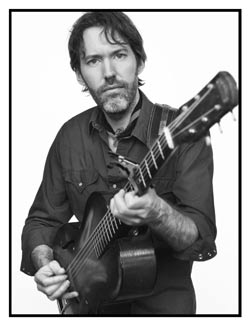

Photo: Mark Seliger

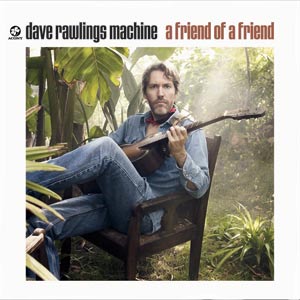

“We’re insane,” says Gillian Welch with a laugh. She’s in Los Angeles, taking a break from finalizing the cover art for The Harrow & The Harvest, her first album in eight years—out June 28. She’s decided to have the package letter-pressed, so she’s taking meetings with printers before driving (yes, driving) all the way home to Nashville. “I don’t know many people who take the album more seriously as a piece of art than we do,” she adds. Such a craftsman-like attitude is hardly a surprise coming from Welch, who has established herself as one of the leading figures in American roots music. She was adopted and raised in L.A. by a husband-wife comedy-and-music team, and met Dave Rawlings, her musical soulmate, at Boston’s Berklee College of Music. Over the course of four acclaimed albums and collaborations with artists ranging from The Decemberists (she features prominently on the band’s hit album, The King is Dead) to soul legend Solomon Burke, Welch came to be celebrated for her stripped-down style and plainspoken lyrics. “Acoustic music is alive and well,” she says. “As it mutates, it helps define our place in the pantheon.”

Mother Jones: So what took you so long with the new CD?

Gillian Welch: It’s not as if I had writers block, I just didn’t write anything I liked, and I know enough at this point to trust myself: If I don’t like ’em, it’s hard to believe that anybody else will. Then, about a year ago, something clicked. I’d been working diligently and this set of songs got written in a pretty condensed chunk of time that sat together, that clearly were a record—I really do think in terms of albums. We probably wrote at least three records worth of material, and I’m okay with that. But the songs weren’t cherry picked over time; they really reflect the last year.

MJ: What was the difference between these songs and the ones that you didn’t like?

GW: We were coming out to L.A. a lot, and the very act of leaving made us think more about Nashville and about the South. At this point, I’ve lived in Nashville longer than I’ve ever lived anywhere, and this certain Southern-ness was coming through. The new songs all seemed to circle around ideas of place and time, things having to do with the passing of time and its effect on friendship, the people in your life—when things don’t go the way you want them to. Which is a great way of summarizing why so much time went by [since the last CD]. At one point there was talk of a double record, but as you focus the vision, it kind of draws its own boundaries.

MJ: The lyrics are full of classic images—Gatling guns and beefsteak and women named Bessie. But you grew up in L.A. Why does this kind of language resonate so strongly with you?

GW: At this point, I’ve assimilated this vocabulary so deeply, I don’t even see it that way. It comes from folk and traditional music, and they’re so alive and not in any way back in time at all. It’s how we are, and the stories that move us. It’s the best way for me to express what’s going on in my world and in my head. This record was also the most intertwined that Dave and I have ever been. Normally, I would begin the narrative and then Dave would get involved. But these songs came out of both of our brains from the beginning. We’ve been working together long enough now that the narrator really is not him or me, but a complete intermingling. The ideas were actually mingled before the songs ever started. We both realize it as a new creative step.

MJ: Is that why you’ve kept it just the two of you—no other musicians?

GW: I think it is. Ever since Time (The Revelator), in 2001, when we started our own record label and started producing ourselves, I’d be hard-pressed to find any more self-sufficient artists out there. That strain of independence, verging on isolationism, always runs through our work. We didn’t even talk about it; it had to be strictly a duet record. That’s our band. We didn’t need any further ornamentation. Once we got these songs together and got into the studio, things went really quickly and intuitively. Most are take one or two—everything is live, just sitting in front of each other playing. It’s just funny to realize that not many people still do that now. I’m really proud of how it sounds, and that’s really saying something, because all we’re trying to do is simply to like the stuff we’re doing. That’s the bar we try to get over.

MJ: You’ve recently decided to do your touring exclusively by car. How come?

GW: There was something we were finding increasingly dislocating about airplane travel, the lack of acknowledgment of space and miles and movement. It’s really grounding to do all the travel in the car—Dave said he feels our thoughts and our selves gathering weight. The topography, culture, and language of this country figure prominently in our work. I mostly read American authors for this same reason. We even stopped taking I-40, which is the fastest way, and started spending more time on I-70, I-10, just moving around. I know it’s part of this record, that we dispensed with the fastest route.

MJ: That sounds a little academic. In fact, haven’t you always had to deal with roots-music purists asking, “but is she authentic”?

GW: I think part of the maturity and comfort of this record is that now the question doesn’t make me a bit uncomfortable. I’m happy that the world has come to the same conclusion. But that’s kind of incidental—the main thing is that I don’t worry about it any more.

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.