<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/soonerpa/5926046676/in/photostream/">Soonerpa</a>/Flickr

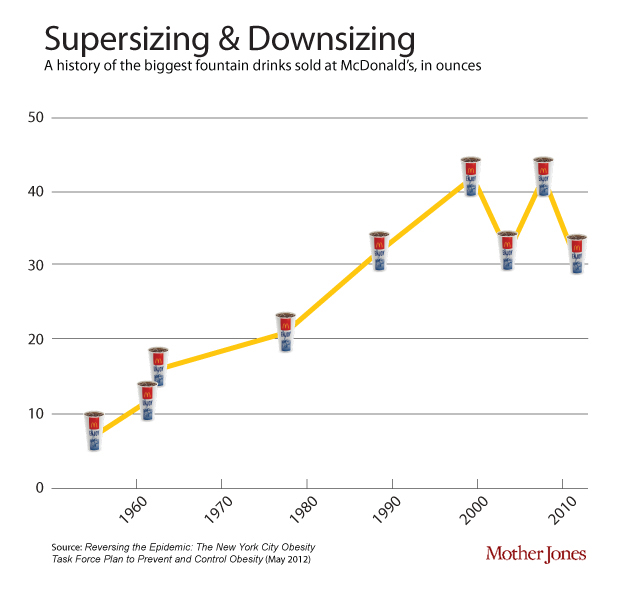

When McDonald’s execs first struck up their lucrative business partnership with the Coca-Cola Company in 1955, they were thinking small—literally. At the time, the only size of the beverage available for purchase was a measly 7-ounce cup. But by 1994, America’s classic burger joint was offering a fountain drink size six times bigger.

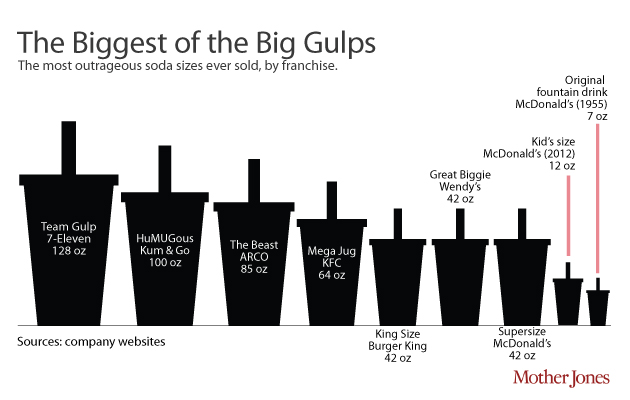

And that’s not even the worst of it. Franchises like 7-Eleven, Arco, and the unfortunately named Midwestern chain Kum & Go have all offered drinks upwards of 85 ounces. (To put this in perspective, this is around three times the capacity of a normal human stomach.) Studies have shown that consumers have a hard time gauging sizes properly, so as fountain drinks continue to get bigger and bigger, it’s less and less likely that we’re able to make informed choices. But how did this problem get so big in the first place? Here’s a look at how super sizes became the status quo.

- 1767: Joseph Priestley invents carbonated water after suspending a bowl of water above a beer vat. In 1772 Priestley publishes a paper on his findings entitled “Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air.”

-

1819: Samuel Fahnenstock files a patent for the first ever soda fountain.

- 1886: John S. Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta, invents Coca-Cola. That year, he sells an average of nine drinks a day—today, the Coca-Cola Company sells around 1.7 billion beverages daily.

- 1955: McDonald’s forms an official partnership with Coca-Cola, offering just a single 7-ounce size fountain drink (PDF).

- 1955: The Coca-Cola Company introduces the first king-size bottles in the United States. In addition to the standard 6.5-ounce bottles, shoppers can now buy Coke in 10-, 12-, 16-, and 26-ounce bottles.

- 1980: 7-Eleven starts selling the 32-ounce Big Gulp. Ads run the slogan, “7-Eleven’s Big Gulp gives you another kind of freedom: freedom of choice.”

- 1986: 7-Eleven follows up its success with a 44-ounce Super Big Gulp fountain drink.

- 1988: McDonald’s launches its Super Summer Size meals, available for a limited time only.

- 1989: 7-Eleven rolls out the Double Gulp, a staggering 64 ounces of soda.

- 1993: McDonald’s launches another summer Super Size exclusive, this time called Dino Size as a tie-in to the film release of Jurassic Park. “Catch ’em quick—before they’re extinct!”

- 1994: Mickey D’s gives Super Size meals a permanent spot on its menu. The fries are three times the size of the original 1950s serving, while the drink is six times bigger than its predecessor.

- 1995: Wendy’s introduces its version of super sizing with the 42-ounce Great Biggie, described as a “river of icy cold enjoyment.”

- 2001: Burger King introduces “King size” fries and 42-ounce sodas as part of its new Value Meals.

- 2003: In the first suit of its kind, Pelman vs. McDonald’s Corp. alleges that the fast-food chain knowingly failed to warn consumers that its products lead to obesity, and that it deceptively marketed food products “that were physically and psychologically addictive.” The plaintiffs are two girls aged 19 and 14, who weigh 270 and 170 pounds, respectively. The Manhattan District Court judge tosses the case, citing individual responsibility. This spurs a new class of litigation dubbed “McLawsuits.”

- 2004: Spurred by the Pelman case, Morgan Spurlock films Super Size Me. Spurlock eats and drinks at McDonald’s three times a day for a 30-day period, making sure to order everything on the menu at least once. He gains 25 pounds and develops serious health issues.

- 2004: Due to intensifying public scrutiny over fast food chains, McDonald’s drops the 42-ounce Super Size fountain drink as part of its new “healthy lifestyle initiative.”

Okinawa Soba/Flickr

Okinawa Soba/Flickr

- 2006: Wendy’s does away with its Biggie and Great Biggie portions, but in name only—instead, the 32 and 42 ounce drinks are the new medium and large.

- 2006: 7-Eleven releases its Team Gulp, a gallon jug for soda.

- 2007: After a huge public-relations sweep (and a resulting quadrupling of stock prices), McDonald’s again offers a summertime-only promotional jumbo drink. Staying away from the Super Size trademark, the new 42-ounce drink is called the Hugo.

- 2011: KFC introduces a drink so big that it has a bucket handle to carry it. In what can only be a cruel joke on humankind, for every Mega Jug purchased, KFC promises it will donate $1 to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

- May 2012: Michael Bloomberg, the mayor of New York City, proposes a ban on sugary drinks exceeding 16 ounces. Days later, the Center for Consumer Freedom, a nonprofit backed by the fast-food industry, buys a full page ad in the Sunday New York Times: “New Yorkers need a Mayor, not a Nanny.”

- September 2012: A second group, heavily bankrolled by the food and beverage industry, says it has collected some 240,000 pledges of support for its campaign to defeat Bloomberg’s proposed ban on oversize sodas. Nevertheless, the New York City board of health votes 8-0 (with one abstention) to uphold it. “NYC’s new sugary drink policy is the single biggest step any gov’t has taken to curb obesity,” Bloomberg tweeted after the vote. “It will help save lives.”