MacKaye shows off his Minor Threat-era skateboard.

I’m drinking green tea with Ian MacKaye in the modest Arlington, Virginia, house where it all began—where Dischord, MacKaye’s legendary do-it-yourself record label, took root more than 30 years ago. Back then, MacKaye was a pissed-off teenager whose straight-edge punk band, the Teen Idles, operated amid the musical wasteland of the nation’s capital, a city too obsessed with dark money and happy hour to care about DIY ethics and $5 punk shows. But MacKaye cared, and he still does, even if Dischord’s flagship acts have long since disbanded. This “is exactly how we started,” he tells me. “For the first few years it was just all of us out of this house. We wanted to make records. Literally, make records. We would fold and cut and glue all the sleeves because that’s what we needed to do to get it done.”

MacKaye cofounded Dischord in 1980 with bandmate Jeff Nelson to put out the Teen Idles’ album Minor Disturbance. And though the Idles split up the same year, MacKaye and Nelson went on to form Minor Threat, whose furious blasts of punk-rock energy influenced a generation of teenage rockers. With proceeds from its founders’ records, Dischord started releasing albums by other local punk acts, including State of Alert (SOA), Faith, Government Issue, and Youth Brigade. By the mid-1980s, most of the early Dischord bands were kaput and the label was struggling financially, but it roared back in the late-’80s as MacKaye’s new band, Fugazi, exploded onto the scene.

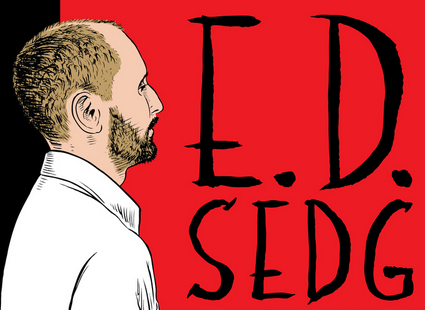

MacKaye at Dischord HQ

A visceral, passionate, politically astute post-punk band that spurned music industry conventions, capping ticket prices at around $5 and insisting on playing for all-ages crowds, Fugazi won over hordes of loyal fans and helped kick off a nationwide movement of DIY bands and record labels. Fugazi and Dischord were living proof that starting your own band, making your own records, and booking your own shows worked. “It was the label that was very exciting at the time,” says Ian Svenonius, whose former bands the Nation of Ulysses and the Make-Up released several albums on Dischord in the ’80s and ’90s. “It had a staunchly anti-commercial outlook and it was explicitly independent and local.”

Not only did being on Dischord make people take notice of his bands, Svenonius says, but the label “gave us a philosophical and ethical framework which we could align ourselves with—or refute—it was an enviable situation.”

In a unpublished interview with Mother Jones senior editor Michael Mechanic, MacKaye recalled a late-1980s visit to Dischord HQ by Dead Kennedys’ frontman Jello Biafra, who noticed MacKaye’s massive collection of hundreds of tapes of DC bands: “He saw that shelf, and he said, ‘What sets Washington apart from the rest of the country is that you guys documented everything.'”

Biafra went on to explain that a lot of the bands in the late ’70s San Francisco punk scene were looking to get signed, so rather than put out a whole album they would make a two-song demo to shop to labels. Most wouldn’t get signed and they’d eventually break up, so it was as though they’d never existed. “But in Washington, from the very beginning, there was a really strong ethic of documentation, where we would just record our bands—all the songs the band knew. And that creates a legacy of something here in DC,” MacKaye said. “There was literally nothing here before that time. There was no notable rock or punk scene.”

Dischord “was a resource which sought to document a scene’s creativity rather than exploit it or launch it towards mainstream commerical acceptance or success,” says J. Robbins, who has known MacKaye since the late 1980s and has released records on Dischord as a member of Jawbox and three other bands. The label, he adds, “was one of the initial inspirations that got me into punk rock in the first place.”

Dischord hasn’t changed much in 30 years—its contracts are still informal, sealed with a handshake—but it no longer has a stable of artists that can draw thousands of people to a show or headline major music festivals. With only a handful of active bands remaining on the label, it might be tempting to question whether it still plays an important role, but the musicians say that’s missing the point. “I think an awareness of Dischord’s DIY, grass-roots origin provides some encouragement for people to move forward on their own terms,” says Robbins. “So energetically it’s still contributing a lot even if the release schedule is not as full.”

Svenonius points out that Dischord is still a key distributor for local bands and labels. And Melissa Quinley, who worked at Dischord from 1997 to 2005, and whose band, Soccer Team, is on the label, says that “it seems silly to pontificate” on the question of Dischord’s continuing relevance. “I’ve got complete trust in Ian and Jeff,” she says. “I never had any lofty Soccer Team goals. I was fine with all the regular promo systems that Dischord had in place.”

MacKaye, of course, isn’t one to worry about what other people think of his label. He just wants to keep putting out mindful music that jibes with one of his personal philosophies, namely “caring…but not giving a fuck.”

Last year, hewing to its role as a documentarian, Dischord began releasing its extensive archive of live Fugazi shows in a pay-what-you-want format. MacKaye wanted to get the material out there, but without compromising the value of the art by giving it away: “There’s a very good chance we’ll never break even on it, but I don’t care. It seemed crazy to have boxes and boxes of recordings that no one would ever hear,” MacKaye says. He talks more about the archive in this video clip:

As it happens, Dischord had two new releases this month. The first is E.D. Sedgwick’s We Wear White, which I un-review here. Sedgwick makes melancholic dance-punk with an acidic aftertaste. Cofounder Justin Moyer used to perform in drag as the eponymous Andy Warhol starlet, but told me he got “tired of wearing a dress all the time.”

Moyer first got involved with Dischord in the early naughties when his former band, El Guapo, figured out how to burn a CD and sent its demo to MacKaye. Moyer has now worked with Dischord on several albums, and says MacKaye’s personal involvement has ranged from “a lot, to just a thumbs up.”

Dischord’s other new record is from MacKaye’s latest band, the Evens. Formed in 2001 with Amy Farina, now the mother of MacKaye’s four-year-old son, the Evens are a kid-friendly indie-rock mashup—albeit with some serious post-hardcore weight behind it. (Farina used to play drums for another Dischord band, the Warmers.) “Part of the Fugazi process was that we really struggled. Everyone had ideas, everyone was an artist, we didn’t always agree. I found working with Amy almost effortless, and that was a real shock,” MacKaye says.

The Evens allow MacKaye to sidestep what he calls the painful paradox of Fugazi—as the band got bigger, it could no longer play in “strange, rebel spaces” and instead was sometimes limited to playing 21-and-over venues where the “alcohol trumped the music.” (MacKaye doesn’t drink or use other drugs.)

By contrast, the Evens tend to fly under the radar. They play unusual venues like art galleries and DC’s St. Stephen and the Incarnation Episcopal Church—places where there are no barriers to entry and the band doesn’t have to max out its volume to be heard. In one song, Farina and MacKaye croon, “The capitol it is your proving ground, your centering. You and yours can keep your scores. But Washington is our city.”

It’s fitting that MacKaye, at age 50, now finds himself settled in his hometown and playing at St. Stephen’s. After all, the church, which his family attended (he no longer does), helped nudge him towards punk rock in the first place. He was only six years old when race riots erupted in DC following the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. On that Palm Sunday, the liberal St. Stephen’s decided to hold its service outside, on 16th Street, in the middle of a riot. “I saw the city basically under martial law. The buildings were still smoldering; there were police and soldiers and firemen everywhere,” MacKaye recalls.

The other thing that shaped his destiny, MacKays says, was going through the DC public school system, where he learned that “if you ask for permission, the answer is always no. So I developed a practice of just doing things.”

And that’s why it’s hard to predict what Dischord will do next: MacKaye doesn’t really think about the future: “My sense is if you’re driving on a curvy road, and you’re staring at point far off in the distance, you’re going to be more likely to run off the road.”

Click here for more music coverage from Mother Jones.

This post has been updated.