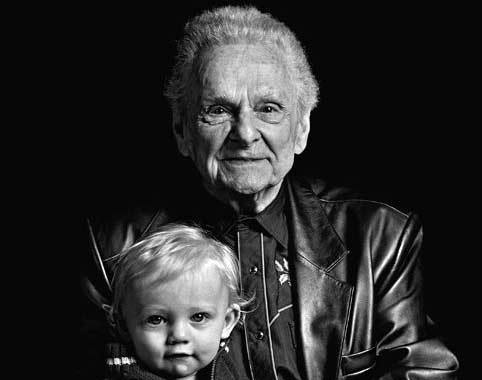

Bruce Molsky on stage in Norway.Knut Utler

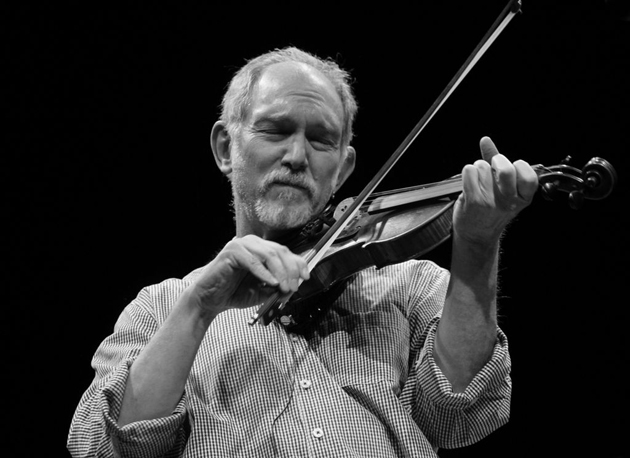

If you haven’t heard of Bruce Molsky, one of America’s premier fiddling talents (as well as an accomplished guitarist and banjo player), it’s probably because old-time musicians, like do-it-yourself punk rockers, are not given to self-promotion. “I was one of those people who should have had the bumper sticker that says, ‘Real Musicians Have Day Jobs,'” Molsky recalls.

Indeed, the Bronx-raised fiddler didn’t quit his day job until he was 40, married, and settled into a comfortable career as a mechanical engineer. Nowadays, when he’s not running fiddle workshops or teaching classes at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, he tours the world performing Appalachian gems mined from scratchy archival recordings, which he revives with his distinctive bowing and clear, droning voice. Some of the tunes are joyful, others hauntingly sorrowful—but all evoke stories of simpler times.

In addition to his solo work—he performs on all three instruments—Molsky always seems to have a few bands on the burners. His more than a dozen albums to date include genre-bending collaborations from the multinational Mozaik to the Grammy-nominated Fiddlers 4. This summer, he’ll unveil the debut CD from a new trio with the Swedish mandola virtuoso Ale Möller and fellow fiddler Aly Bain. I caught up with Molsky in advance of his recent solo effort, If It Ain’t Here When I Get Back, to talk old-time and old times. But first, check out this rousing rendition of the traditional tune “Chinquapin Hunting” at last year’s Pickathon in Portland.

Mother Jones: Is it true you didn’t even pick up a fiddle until you were 17?

Bruce Molsky: Well, I played guitar already, and I picked up the banjo about six months before I picked up the fiddle, and all the banjo did was to make me realize that what I wanted to play was the fiddle.

MJ: What are the biggest differences between playing classical violin and fiddle?

BM: The way you hold the bow, the way that violinists are trained to produce a note, is really different. I’m not an expert in classical music. I don’t want to say something that ends up in print and somebody comes running after me with a shovel, but they’re taught for each note to stand alone in a very deliberate kind of way, which is really different than how notes are strung together in old-time music to create rhythm.

MJ: You never had any classical training?

BM: No, I’m self-taught.

MJ: How long does it take to develop a unique style?

BM: I’m sure I played for 10 years at least before I started to realize I didn’t sound like any of my heroes. I tried to be Tommy Jarrell for a while, and I tried to be William Hamilton Stepp for a while. I tried to be a whole bunch of different people. And I woke up one morning a whole lot later and realized I didn’t sound like any of them; I sounded like me.

MJ: In what way would you say your playing is distinctive?

BM: I’ve kind of codified certain things for myself, rhythmic patterns and mechanical ways of using the bow to create layers of rhythm. What I’m trying to do is to create a complete piece of music on one instrument.

MJ: You’re one of relatively few fiddlers who sing while they play. What’s your secret?

BM: There are things about how a note sounds on a violin that are really analogous to the human voice—you have a frequency and the air, and then you have a timbre which really is overtones—and making those things work together is one thing. The other thing is mechanical: If you can use your hands and arms to create sound on a fiddle, then learning to sing with it is like adding a third body part. And it’s all training. I wanted to sing with the fiddle ever since I started to play, and when I first started to do it, I had very set ways of moving the bow—the arrangements to the songs were really specific because I was trying to make everything operate all at once. Over a period of time you get stuff more into your muscle memory and it enables you to think ahead. If you can think a few bars ahead then you can see the light of the path in front of you—you can see your choices. [In the clip below, Molsky plays and sings “Lazy John,” followed by “Rebels Raid,” a tune William Hamilton Stepp recorded with Alan Lomax in 1937.]

MJ: I would describe your voice as unadorned. It’s actually kind of like a fiddle. There’s a drone aspect.

BM: [Laughs.] I like to think that the fiddle has taught me to sing, in some way.

MJ: You’re also a bit of an ethnomusicologist. What do you look for in these old recordings of guys like John Salyer? [Below, Molsky performs the Salyer tune “Jeff Sturgeon” to accompany clogger Nic Gareiss at a music camp performance.]

BM: I’m really just looking to be moved by music. All my kind of hero fiddlers, their playing is beautiful to me for different reasons. I spend way more time listening than I do playing. I always have. And sometimes I’m listening for right-brain kinds of things, sometimes I’m listening for left-brain kinds of things. The great Kentucky fiddlers like Salyer and Bill Stepp and Luther Strong and those guys, to me what they do on the instrument is just the language. It’s the story they tell—how they speak. You can always tell when somebody is more fixated on their virtuosity than on using it to tell a story. Me, I’m way happier with something simple, played with great expression.

MJ: Which can sometimes be more challenging to play.

BM: In a way it is. Sometimes when I teach a student something that I think is really simple, I realize I’m teaching them something they can do 90 percent of really easily and the last 10 percent is going to take them 10 years.

MJ: The Bronx seems like an unlikely provenance for a guy whom your friend Darol Anger calls the “Rembrandt of Appalachian fiddling.” Tell me about your upbringing.

BM: I grew up in very much a middle-class family. My father was a building contractor, a mechanical engineer. He worked for a company that built air conditioning duct work for office buildings. My mother never graduated high school, and she was a housewife most of the time that she was raising my sister and me. I’m the younger of the two. My mother was a very family-oriented, very loving person who died way too young.

MJ: How old was she?

BM: She was 52 when she died. And she was the youngest of four sisters and they all went in opposite order. I’m Jewish, but not deeply religious. We were active in a very liberal synagogue, and I was conscripted to go to Hebrew school and do all that stuff when I was growing up and I got away from it as quick as I could when I was done. But it was all more a matter of, you know, I’m second-generation American, so a lot of those things are cultural things that stay. So culturally I was very much that. I grew up in a fairly diverse neighborhood and I went to city schools. I was just a street urchin like everybody.

MJ: Was there much music in your household?

BM: There were no music freaks or aficionados in our immediate family. Only my mother singing around the house. She loved Carole King. She sang Yiddish folk songs, because my parents spoke Yiddish. We had a lot of show music. My interest in music started really early, so I drove them crazy with AM radio, because that’s all there was.

MJ: What inspired you to pick up an instrument?

BM: We had a program in the New York City schools called Jazzmobile, where they brought well-known jazz artists and educators into the public schools. And Dr. Billy Taylor, the guy that started it, he came to my school. I guess I must have been like 11, and it just hooked me. He played piano and talked about music in terms that the kids could understand and he handed out these cool 45 rpm records. One of the songs was “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free,” which was one of the things he played. And he described it as something he wrote to teach his niece how to play the piano. And I thought, “Man, I could do that.” I went home and I asked my mom for guitar lessons. And that was it. I took lessons for like nine months from a guy around the corner.

MJ: You obviously kept it up.

BM: Yeah, I was dug in so deep. He was just teaching kids to sing, “Black, Black, Black Was the Color of My True Love’s Hair” and doing the first five pages of the Carcassi Classical Method, and here comes me, and he couldn’t deal with me.

MJ: Did you learn after that by playing along with records?

BM: Yeah. I loved rock. I mean, it wasn’t any one particular thing. My sister bought me Doc Watson’s first LP when I was like 12 and I heard “Black Mountain Rag” and it just sent me over the moon. And I loved Jimi Hendrix. I still love Jimi Hendrix.

MJ: Did you play with other people?

BM: I was in a string of terrible rock bands. There were concerts in New York, too, that I kind of hooked into. I got to see Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys, and Ralph Stanley, and Curly Ray Cline, and Tex Logan.

MJ: After high school you studied architecture and engineering at Cornell.

BM: For two years. I didn’t finish. My grandfather and my dad’s brothers and my dad all worked in construction. It’s the whole cultural thing, you know, your parents want you to go to the next level of whatever, and I decided that I ought to be an architect. I can’t tell you why. And I tried, and I had no aptitude for it.

MJ: But I gather those two years were sort of your musical awakening?

BM: They really were. And it was not an easy awakening because it was not the set path for somebody like me. I went to college, I failed at it a few times, and the last time I realized it just wasn’t going to work. I kept insisting on studying engineering because I thought that was what I was supposed to do. A few years after Cornell, I got a job working in a carpet mill in Virginia.

MJ: What did you do in the interim?

BM: I kind of kicked around. I went to a couple of different schools. I worked at a couple of tobacco shops in New York. I sold pipes and cigarettes and blended people’s personal tobacco blends and I just really wasn’t sure what the hell I was doing. [Laughs.]

MJ: What about music?

BM: That actually was a very strong developing time for my music because that was when there were music sessions going on in Manhattan and I’d go every week. Before they restored the whole South Street Seaport neighborhood, it used to be just a bunch of piers and stuff, and they had a fiddlers’ convention there every year. That’s really when I started playing old-time music. I’d first heard it at Cornell because the Highwood String Band was really active at that time and they lived just outside of there and they were a force.

MJ: Did you get to know those guys?

BM: Yeah. [Highwood banjo player] Walt Koken gave me my first banjo lesson. I was just this punk kid, you know.

MJ: You moved to Virginia for the old-time music scene?

BM: Yeah. My mother passed away in ’75 and I was really kind of at wits end. I really didn’t know what to do. School wasn’t going well and my dad was having a tough time.

MJ: Was he freaking out about your prospects?

BM: Oh God, yeah. It was only out of love that he was trying to push me in what he thought was the right direction. It was his generation. He was a Depression kid, you know.

MJ: So you got a job in a carpet mill. That doesn’t sound pleasant.

BM: Well, I moved to Rockbridge County, Virginia, and I lived on some friends’ couch for a while—all great old-time musicians. They all came from other places and they were renting this dilapidated house. I eventually got a little place to live and ran out of money. So I went to Burlington Mills, a huge carpet factory, just to fill out an application. At the bottom there was a little check box that said, “Check here if you can read mechanical drawings.” I’d seen mechanical drawings all my life because my dad would always bring them home. They called me the next day and said, “Nobody in Rockbridge can read mechanical drawings. You’re hired!” And so I got a factory job laying out carpet manufacturing machinery.

MJ: What were you seeking, music-wise?

BM: I just wanted to be where the action was and learn and play with people and be part of the community. In Lexington, at Washington and Lee University, there was a geology professor named Odell McGuire who was a really good banjo player. He was kind of like the Pied Piper for everybody in the old-time scene. He knew all the old guys that lived in the mountains all around West Virginia and Virginia and we’d take these caravan road trips to visit all these old players. You’ll find a high percentage of people that played old-time music in Rockbridge County were geology majors!

MJ: You also met Tommy Jarrell. [See clip below.] Did he become a mentor to you?

BM: In my own mind, yes. In truth, I didn’t spend enough time with him to really consider myself a student of his. But he was my hero. I visited him a bunch of times.

MJ: What appeals to you about old-time culture?

BM: I’m a city kid. I know it now, but at the time I wanted to be somebody else. You had the back-to-the-landers, which I never was—I could kill an air fern; I never could grow anything. But I think just the attraction of something different and something that appears to be simpler. Even maybe a little bit the rigidity of the culture; it’s not very open-minded, but there was something about it that was attractive. You know, I worked at a factory. I hooked up with all the old guys. I joined a Mason’s Lodge—what was I thinking? And I married a girl from down there for a very short time.

MJ: You went all in!

BM: Yeah, that’s how I do. [Laughs.]

MJ: But you could never fully assimilate?

BM: Uh, yeah. I never felt unwelcome, but I never felt like one of them. And I have tremendous respect for those older people who grew up before radio and TV made everything kind of the same for everybody. They had a really strong sense of their roots.

MJ: Why did you leave Virginia?

BM: [Pauses.] I guess I just decided I wanted to try and have a career again. I had another college try, and soon after that I met my current wife, Audrey. We’ve been together for 32 years. And she had a similar background—a New Yorker who moved south for the same sort of attraction. She danced with the Green Grass Cloggers, a real well-known group. But she’d been doing it for awhile and she was looking for something else, so we moved to Atlanta because I had a job down there and we ended up being professional people. She went to work for IBM.

MJ: But you were still pursuing your music pretty seriously?

BM: Oh God, yeah. Audrey is a great guitar player and we played music all the time. There was enough community of that down there to keep us happy. I was teaching at a lot of music camps and wherever the music was, we would go there. There was a road trip every weekend.

MJ: Why did you wait until you were you were 40 and your dad had passed away before having a go as a professional?

BM: Because, honestly, it would have broken his heart. I just couldn’t do that to him, as weird as that sounds. The last engineering job I held I was a foreman. I stayed there for 10 years and I was getting tired of it. I was playing more and more music and I guess I was saving for my retirement to play full-time music, and I just had this wake-up call one day—what am I waiting for? Audrey and I didn’t have kids, we had no encumbrances. I went home and I asked her about it one day and she says, “I can’t believe you didn’t do this 10 years ago.” So I left my job and I never went back.

MJ: So was it scary for you to make that leap to pro musician?

BM: I was nervous about, you know, my security blanket, and I learned some pretty big lessons from that: Strength doesn’t come from what you do, strength is from who you are. The day that I went in and gave my notice, I felt great. I felt like I had given myself the gift of being able to do anything I wanted to do. And being the way I am, I had booked quite a few months of gigs in advance. I wasn’t just throwing myself into an open hole or anything. I always took it seriously from that end.

MJ: You tour extensively in the UK. How is that different in terms of your reception and the crowd demographic?

BM: The demographic, like here, is getting older. But there’s also a young group that’s kind of coming in underneath. When I play music here in the US people are generally culturally close in some way to where it comes from. They have some notion that the music is from the South and what Southern people are like and this and that. When you play it in another country, people don’t have that sense. I really get the feeling they hear the music more for what it is, just as an expression, and that’s led me to a lot of collaborative things, going-outside-the-box kind of things. I think people in the States also want to hear something new. But in Britain, I’m the something new, if that makes any sense.

MJ: Do you sell a lot of records?

BM: I don’t know what “a lot” is. I’m not Alison Krauss. I certainly sell enough to where it’s worthwhile.

MJ: Your albums are distributed by Rounder and Compass, but you also have your own little Tree Frog label. What’s that about?

BM: Tree Frog Music has been the name of my little company since my very first solo recording, Warring Cats. Rounder or Compass distribute the CDs that I made under their license and sell me CDs wholesale that I sell at my shows. The new recording is a self-produced thing because I just wanted to go through that process again. I’m a hardcore do-it-yourselfer, and this recording is all unaccompanied stuff.

MJ: What would you say makes old-time music distinctive from other folk and country genres?

BM: I think just the kind of rhythmic sense. There’s so many regional styles. I don’t want to generalize, but a lot of the stuff I like, the melodies are very rhythm-based, and so you don’t have long strings of eighth notes. Midwestern American fiddling is a lot more melody based, but the Southern mountain stuff, like the stuff that Tommy Jarrell played, and all the way down to North Carolina and Georgia and Alabama, that stuff, the rhythm in the bow is totally locked in with what’s happening on the melody. Neither of them is anything without the other. I think that’s why I like Scandinavian music so much—because it kind of does the same thing.

MJ: The internet has made old-time culture and music far more accessible. Is that a good thing, or does it sort of spell the end of regional flavor in American folk music?

BM: The regional flavor went away a long time ago. If you want to pursue that, you know, as a point of interest, it’s out there, and the internet really helps with that. It’s just different now. When we were first getting into the music, the community was tight-knit in a different way. When somebody would discover something, you would make a cassette copy of a cassette and send it to your friends, and so we had this kind of postal mail network of sending tunes around and talking on the telephone about them. The internet brings more people together, but not in a more personal way. But I think it’s really great that you can Google Luther Strong and find out everything that he ever did. And in a way it doesn’t matter whether I think it’s good or not: It’s inevitable. [Below, Molsky plays “Last of Callahan,” a tune Luther Strong recorded with Alan Lomax in 1937.]

MJ: Do you feel like the old-time scene is too hung up on the notion of authenticity?

BM: That’s nothing new. There are people that appreciate the music for its musical value and there are people that will always think that it should be reserved as an expression for people who grew up with it.

MJ: Or that it has to be played in this very specific way.

BM: Yeah. And some people ascribe a right and a wrong to it. I don’t. I think if you’re respectful of it, and know how it goes and really study it, then I have no problem with you using it as your own free expression.

MJ: The old-time scene seems pretty old, by and large. When I go to a jam, I don’t see many people under 40. As someone who tours around a lot, do you feel like enough young people are gravitating to this music to keep the tradition alive?

BM: I think it goes through cycles and kind of waves of interest. I think it was just kind of getting older with the older generation for the last few years, but I think that’s changing now. If you came to Clifftop [Appalachian String Band Festival] in West Virginia in August you’d see there’s a whole lot of young people—flats of beer and fiddles playing all night, and kind of going back to the old masters and all that stuff. It’s happening again, it’s totally happening again! I don’t think it can go away for too long, it’s too good!