Peter DiCampo

ON A BRISK JULY morning, hundreds of miles from his art studio near Vancouver, Robert Davidson hikes toward the ruins of a village on Haida Gwaii, a remote rainforest archipelago off the coast of British Columbia. Along the hushed trail to sGang gwaay Ilnagaay, stands of old-growth cedar and Sitka spruce jut into a gray sky, some with trunks so thick it would require 10 people to encircle them. A large raven takes off from the foggy canopy in a whoosh of black.

“When I was a kid, we played in forest like this,” Davidson says, recalling his village of Massett at the north end of the islands. “We had forest spirits who took the form of small humans. They were quite shy. We would try to catch glimpses of them and they would be gone.”

Davidson isn’t recounting a fairy tale—he’s casually explaining the regular presence of supernatural beings in Haida life. “I have a cousin who had lots of them around recently,” he continues. “She has lots of junk in her house, so she said, ‘Okay, if you’re all going to be here then you can help out.'”

Davidson, who at age 67 has silver-gray hair and deep-set dark eyes, has a way of shifting from laconic understatement to dry hilarity in a heartbeat. “She meant they could help clean up,” he says, cracking a wide grin. “After that, they were gone.”

The trail approaches a rocky shore, and then we see them: a cluster of ash-gray poles, fractured and drizzled with moss, bearing the ghostly outlines of their carved figures—the raven, the grizzly, the killer whale. These are the remnants of 32 totems that fronted the village before its inhabitants fled a smallpox outbreak more than a century ago. “The legacy they left behind is astounding,” Davidson muses.

As recently as 60 years ago, Haida culture—once among the most sophisticated and powerful in North America—was on the brink of vanishing. Davidson has been pivotal not only in reviving it, but also in elevating it among the world’s art curators and collectors. His pieces reside in major museums, and he’s done commissions for everyone from Pope John Paul II to Damien Hirst to Diana Krall and Elvis Costello. In mid-November, Davidson’s first major solo exhibition in the United States opens at the Seattle Art Museum, and it will travel from there to the National Museum of the American Indian in Manhattan in spring 2014.

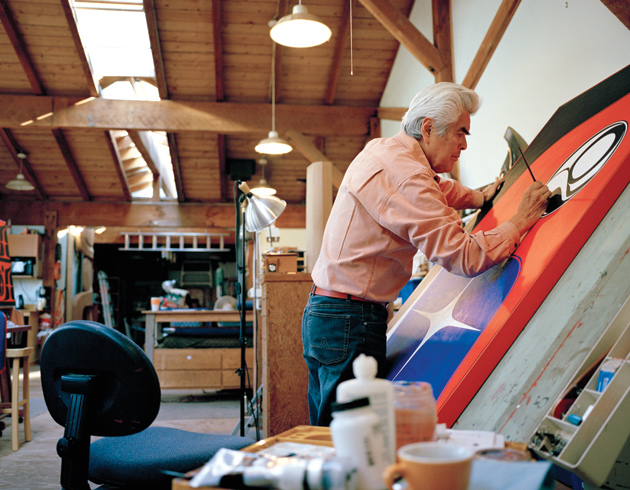

Rare is the visual artist whose work spans such a wide range of media. Davidson is renowned not only for his carved totem poles and masks, but for his printmaking, painting, and sculpture, which transform Haida imagery using inventive shapes and vivid colors. Wrought in aluminum and housed at the National Gallery of Canada, his 10-foot-tall Supernatural Eye twists traditional Haida iconography into three dimensions. Southeast Wind, a five-foot-tall canvas, flows with thick shapes in deep black and a signature brilliant red—Robert Red, as it’s known among his collectors. The story of his art is “the story of a remarkable recovery of the Haida artistic vocabulary and…an expansion of that vocabulary,” Ian Thom, a top Canadian curator, has written. It includes “a vigor and visual boldness which is startling to those who are more familiar with traditional forms.”

For Davidson, it’s about making the old ideas accessible. “I want my images to have their own strength,” he says, “so that a person does not have to have any knowledge about Northwest Coast art to appreciate them.” Nor does he view his creations as objects simply to be appreciated in a gallery or museum—their purpose is nothing less than to help rebuild a culture known, before it was decimated, for being replete with art in every aspect of daily life. Some of his pieces even figured in a government hearing pitting the Haida Nation against the oil industry.

It all began more than 40 years ago when Davidson first dreamed of creating a massive totem pole, not unlike the haunting relics that stand before us on this summer day. It would be the first one raised in his homeland in nearly a century.

FOR THOUSANDS OF years Haida Gwaii was a place of unimaginable bounty. The wing-shaped stretch of some 150 islands blanketed by mountains, forests, and rivers was a kind of Eden in the North Pacific, crepuscular and rain-soaked much of the year. A wealth of shellfish, halibut, and salmon sustained the locals, who stocked their post-and-beam longhouses during the mild summers and concentrated on communal and political matters through the dark, wet winters.

The Haida had no written language, and no word for “art,” yet their villages were suffused with it. They used the giant cedars not only to build homes and oceangoing dugout canoes, but also to create elaborate masks, drums, rattles, bentwood boxes, hats of woven bark, and totem poles—all “mediums for transferring knowledge,” as Davidson describes them. The lofty totems displayed family lineage and rich histories in which the Haida commingled with supernatural beings.

After Europeans arrived in the late 1700s and established a trade in sea otter furs, the Haida gained metal tools, making their esteemed carvers all the more prolific. One visiting Frenchman marveled at the “painting everywhere, everywhere sculpture, among a nation of hunters.” “Their genius,” the scholar Marius Barbeau observed two centuries later, “has produced monumental works of art on par with the most original the world has ever known.”

Sporadic waves of disease also arrived with the Europeans, and in 1862 a devastating smallpox plague struck, wiping out dozens of Haida villages. Most of the survivors took refuge in the two main enclaves that remain today: Skidegate, in the central region, and Massett in the north. Of a people who once numbered an estimated 10,000 or more, fewer than 600 remained by the 1920s. The Canadian government, intent on purging indigenous populations of “primitive” ways, outlawed their customs. Haida children were hauled off to abusive Christian residential schools from which they would eventually return as strangers in their own land, and unable to speak their native language.

The period that followed is known among some Haida as “the silent time”—Davidson calls it “the void.” He recounts how he and his childhood buddies loved watching cowboy-and-Indian movies: “We would cheer on the cowboys because we knew the Indians lost 99 percent of the time,” he says. “When my uncle pulled me aside and told me that I was Indian, I just cried in disbelief.”

Davidson, whose Haida name is Guud San Glans (Eagle of the Dawn), was born in 1946, in Hydaburg, Alaska, where a small diaspora had settled. The family soon relocated to his father’s native Massett. The region’s old-growth forests had lured a thriving timber industry, and some Haida made a living in logging or fishing, but poverty and alcoholism spread along with the boom-and-bust cycles. The Haida language was slipping away, and the few Haida who continued to carve mostly made tourist curios. The elders rarely spoke of what had befallen them.

Davidson learned the basics of carving from his father, and after relocating to Vancouver in 1965 to finish high school, which stopped at 10th grade in Massett, he had an epiphany when he came across some of his ancestors’ carvings in the city museum. The experience was a leap into the spirit world, he recalls, like being in “dreamland.” He soon began working under other carvers, including Bill Reid, a former Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio announcer whose interest in his own Haida heritage had propelled him into a second career. Reid’s creations, including the large-scale sculptures that would become his most famous, were profoundly influenced by the work of the legendary 19th-century Haida carver Charles Edenshaw—Davidson’s great-grandfather. Reid brought renewed attention to the art form, collaborating with anthropologists and writing eloquent essays about his ancestral culture.

But the ways the Haida breathed life into their creations through ceremony remained a puzzle of fading memories. The potlatch, the paramount gathering where clans debuted valuable carvings and distributed names, crests, and property, had been banned for more than 60 years. On a trip back home, hungry for knowledge of the old ways, Davidson knocked on every single door in Massett, trying to hunt down any remaining ceremonial works. He found nothing but a carved box and a bowl.

Davidson was just 22, but he knew what he had to do: He would carve a totem pole. Some of the elders, now devout Christians, frowned on the idea—why dwell on the past? But others encouraged him, including his father, Claude, who spent two weeks searching the forest for a suitable cedar. “Holy shit, what did I get myself into?” Davidson remembers thinking when he laid eyes on the massive log. The pole—carved with the help of his younger brother, Reg, who also would become an accomplished artist—took four months to complete. For the ceremony, Davidson consulted his grandmother, Florence. With no traditional masks to be found, she called for a brown paper bag, cut eyeholes in it, and pulled it over her head to help her recollect the appropriate spirit dance.

Hundreds gathered on August 22, 1969, for the raising of the Bear Mother pole. “No one living has ever witnessed the raising of a totem pole for the Haida,” William Mathews, then the 84-year-old hereditary chief of Massett, told a reporter in attendance. Its red-and-black figures soared 40 feet into the sky, just a few yards from the whitewashed town church. Some elders found themselves recalling songs, and the community sang, danced, and drummed deep into the night. “The totem pole caused an incredible change in my life,” Davidson recalled years later, “in my understanding of ceremony, of what art means to the people.”

BY THE EARLY 1980s, commissions were rolling in, yet Davidson felt his art was incomplete. The void remained present in his work—often expressed as negative space—and in his life. One of his most ambitious early projects, an ornate longhouse honoring his great-grandfather that took two years to complete, was destroyed by arson in 1981. To help mourn the loss, he asked his brother Reg to carve a mask depicting his personal “helper spirit”—a frog—which had been a key figure in the structure’s design. After using the mask in a ceremonial dance, they burned it.

But the void would not be easily overcome. Davidson’s parents, part of a generation brought up in the residential schools, “numbed their pain” with alcohol. “I don’t even know if they knew it was pain,” Davidson says. He feels it acutely himself.

“There was an incredible break in the link,” he tells me one afternoon in his studio. Despite his tranquil optimism, Davidson worries that his efforts are inadequate to meet the challenges his people face. “I feel like we’ve lost our thinkers in this holocaust,” he says. “I’m willing to put my neck out there and say, ‘Okay, we haven’t dealt with the decimation of our population down to 5 percent.’ When I do bring it up, people kind of look at me as if I’m crazy. My generation, I feel, has the biggest responsibility to relearn as much as we can if we are to carry on reclaiming our Haida-ness.”

Over the decades, this sense of duty has driven Davidson to pursue activities he sees as inseparable from his art: hosting feasts and potlatches, creating ceremonial clothing and masks, teaching free design workshops, mentoring young apprentices, and cofounding the Rainbow Creek Dancers, a group that has revived the practice of dancing art into being. His mission is rooted in his relationship with the beings he depicts, says photographer Ulli Steltzer, who documented Davidson at work for two decades: “This is why his figures are so powerful. For him they are alive.”

At a performance by the Rainbow Creek Dancers in Bellingham, Washington, a chorus of voices and throbbing of drums gives way to applause as Davidson and other troupe members prepare to showcase his cedar mask, Eagle Transforming Into Itself. Modeled after an Edenshaw work from the 1880s, the imposing visage, painted black with deep green, is hoisted atop a dancer’s head. Using a built-in lever, the dancer splays open the mask’s broad beak to reveal a second face, a spirit within.

Davidson, dressed in a three-piece ceremonial outfit bearing his designs, sets down his drum and picks up a microphone, beaming. “What’s exciting for me and my generation,” he tells the crowd, “is that we showed up in the nick of time.” As the drums and voices resume, the eagle’s profile begins to undulate and take flight.

THERE IS AN OLD Haida expression: “The world is as sharp as the edge of a knife.” Traditionally it refers to moving through life with balance. Davidson says for him the knife’s edge is the border between ancient cultural knowledge and its expansion in the present. He and other Haida leaders have cited their connection to the natural and spirit worlds in political struggles over the nation’s territory—the site of a tense 1985 standoff over clearcutting. Years of negotiations eventually led to joint federal and tribal stewardship of the now-protected southern region, but in the broader fight over land rights, the government argues that the Haida must prove in court that their claim to the land predates the founding of Canada.

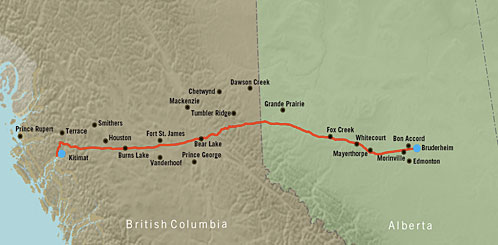

A couple of years back, Davidson spoke at a government hearing on a proposed transcontinental pipeline project that would route oil tankers through Haida waters. His wife and artistic collaborator, Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson, who is the lead attorney for the Haida Nation, assembled a dozen cultural leaders and entered 10 of Davidson’s works into the record to exemplify Haida traditions predating Europeans. “Haida art is derived from the land and waters,” Davidson testified. “Every prominent landmark and many places in the ocean are dwelling places for supernatural beings, which are deeply meaningful in Haida culture.”

A few days after the hearing, I met Davidson for dinner at Bishop’s, an upscale Vancouver eatery whose walls often display his work. Indigenous art holds high cultural status in Vancouver these days: It’s found in galleries around town, in the city’s landmark Stanley Park, and at the international airport, home to a large aerial Davidson sculpture called Hugging the World. But artistic recognition does not necessarily equate with political currency, and sovereignty over Haida Gwaii remains a contentious issue. I asked Davidson what the government officials thought of his talk of spirits. “They listened,” he said, pausing. “I think they were open to it. They said they’d never heard anything like it before.”