Photos by Mads Nissen/Panos Pictures

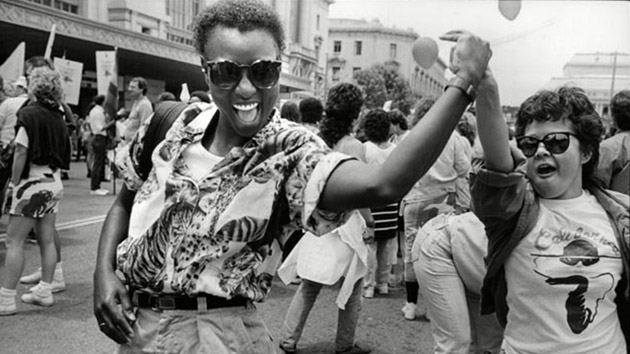

On June 28, 2013, five couples in wedding finery piled into a white limo and pulled up to a municipal office in St. Petersburg, Russia. The same-sex pairs had come to apply for marriage licenses they knew they were unlikely to get, but they wanted to make a statement. A video of the day shows confounded clerks unsuccessfully trying to keep the beaming lovers out as they head to a waiting room where they kiss in protest. “They didn’t even want to give us the blank applications,” says Yana Petrova, who tried to marry her partner, Elena Davydova. “But there wasn’t much they could do—we’d already downloaded them.”

Just two days earlier, the nation’s upper house of parliament had unanimously passed a bill banning “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations among minors” and imposing fines between $120 and $30,000 for offenders. The bill was understood to prohibit all open expression of gay identity, from parades and rainbow flags to same-sex couples holding hands in public. President Vladimir Putin signed the bill into law on June 30.

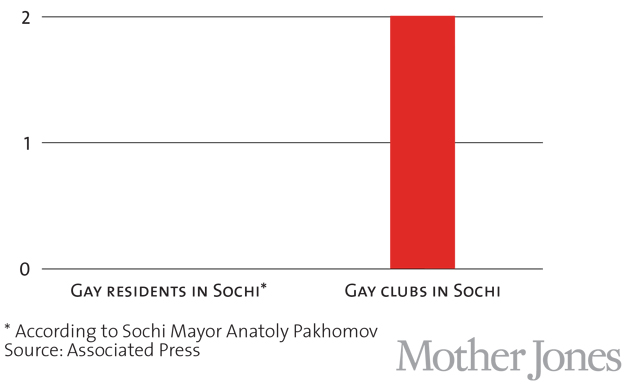

The new law, which has drawn worldwide criticism and inspired calls to boycott the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, further codified Russia’s widespread homophobia: 12 cities, including St. Petersburg, had already passed similar measures, and surveys suggest more than 70 percent of Russians believe LGBT people should remain closeted. Last year, Moscow enacted a century-long ban on gay-pride events.

Since the gay-propaganda law passed, activists have noted a sharp uptick in anti-gay violence. Yet some also say the law has bolstered their cause. “Before, it wasn’t accepted to talk about this,” Petrova says. “Now, there are no neutral people left. Everyone wants to express their opinion. That’s good. Debate is the only thing that can lead to any battle or change.”

Danish photographer Mads Nissen was in Russia teaching a photography workshop when Article 6.21 passed. A student tipped him off to the wedding registry attempt. The activists he met were suspicious at first, asking him to share his website and other information to test his intentions. (Anti-gay activists have attempted to infiltrate Russia’s LGBT community.) But soon, they were bringing him to underground clubs and spaces where the community gathers, and sharing their stories of being assaulted and arrested. At one gay-pride rally, Nissen witnessed a brutal attack on Kirill Fedorov, a young gay man and activist he’d been following for several days. “An anti-gay activist just came up to him and punched him in the face,” Nissen recalls. “In that moment, this wasn’t a theoretical thing anymore. It was real. It was happening. It was worse than I imagined.”

“Sometimes you do a story—you think it’s a big topic, and then when you get into it, it doesn’t seem so bad,” Nissen says. “This was absolutely the opposite. The more I got into it, the worse it was.”