Ron English/George McGovern and the Democratic Insurgents

The campaign poster is typically more science than art. The final product, after rigorous vetting by focus groups and campaign bureaucrats, may send a clear political message, but it’s rarely worth hanging on your wall—let alone at the MoMA. But there are some striking exceptions, most of them from just a few campaigns.

Amid the Vietnam War, the battle for civil rights, and the waves of student rebellion, the 1968 anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy (not to be confused with the anti-Communist GOP Sen. Joe McCarthy) and 1972 candidate George McGovern inspired countless famous and not-so-famous artists to churn out a visual feast of bold and experimental posters. Historian Hal Elliott Wert has collected the best examples from this tumultuous era and assembled them in a new book, George McGovern and the Democratic Insurgents. McCarthy and McGovern both met their maker at the polls, however, and the subsequent years gave us a mere sprinkling of noteworthy posters.

The next great outpouring of campaign art didn’t come until some 40 years later, with the nomination of Barack Obama. “It is possible…that the great American political poster, like so much print media, is a thing of the past,” Wert writes. “If that is the case, the treasure trove of campaign posters created during the 2008 campaign will become known as a magnificent last hurrah in a history that began in the 1840s and continued for nearly 170 years.”

Most campaign posters from the last half-century are buried in landfills somewhere. But thanks to Wert and a few other campaign art connoisseurs, we can step back from the current tweet-fueled presidential race and revisit the artful ghosts of elections past. (For another side of that history, listen to Whistlestop, John Dickerson’s great podcast.)

Here are some examples from the new book. We’ll kick off with McCarthy, who began speaking out against American involvement in Vietnam as early as 1966. Two years later, he ran as the peace candidate in the Democratic primary against President Lyndon Johnson. And although he lost the nomination, McCarthy won the race for innovative posters. This one is considered among the best of the 1960s:

The 1968 race also included Black Panther spokesman Eldridge Cleaver, whom the radical leftist Peace and Freedom Party selected as its presidential nominee. Cleaver attracted few votes, but he became a symbol of African American rebellion—indeed, he was wounded in a shootout following an April 1968 ambush on a police station in Oakland, California. (At the other end of that year’s ballot was segregationist George Wallace, representing the American Independent Party.) This Cleaver for President poster may not cut it in an art museum, but it doubtless deserves a place in a history museum.

In 1972, Rep. Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman to run as a major party presidential candidate. The Brooklyn congresswoman, who described herself as “unbought and unbossed,” won the New Jersey Democratic primary but lost the nomination to George McGovern. She survived three assassination attempts during that campaign. This memorable poster, created by activist ex-nun Mary Corita Kent, is inscribed with a Langston Hughes poem.

By 1972, the year the accomplished pro-peace Sen. George McGovern became the Democratic nominee, the party was deeply fractured. “The civil rights movement was in turmoil, the counterculture was rapidly disintegrating, and the antiwar movement was in shambles,” Wert writes. Against all odds, McGovern secured the nomination and the left rejoiced. An explosion of bold images followed, including Robin McGovern, which circulated as a poster and button. Artists may have adored McGovern, but he lost to Richard Nixon by a landslide in the general election. Journalist and author Hunter S. Thompson, speaking with McGovern later about what could have led to such a decisive loss, asked, “Do you think you ran a ’68 campaign in ’72?” McGovern admitted that perhaps that was the case. Americans had simply moved too center-right in reaction to the turmoil of the 1960s.

After McGovern’s defeat, creative campaign posters went on a general hiatus. But every race had a few gems. In 1984, Democrat Geraldine Ferraro became the first woman named as a major party VP candidate. This poster, playing off the famous French painting (minus the boobs) depicts her as Lady Liberty leading the charge for the Equal Rights Amendment. Ultimately, she and nominee Walter Mondale lost to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush—almost as badly as McGovern lost to Nixon in 1972.

Running against Mondale in the 1984 primaries was the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the first viable black candidate. (Chisholm’s candidacy was so ahead of her time that even she admitted she had no chance.) Artist Jack Hammer created this colorful image to represent Jackson’s platform of inclusiveness—the so-called rainbow coalition. (Click here to read our piece on Jackson’s efforts to diversify Silicon Valley.) Though he ran again in 1988 and did well in the primaries, winning almost 30 percent of the total votes, he was outdone by Michael Dukakis, who garnered about 42 percent.

Dukakis’ 1988 bid was renowned artist Roy Lichtenstein’s first foray into presidential campaign posters—although Time magazine had previously commissioned him to do a Robert Kennedy cover during Kennedy’s 1968 run. Dukakis won the Democratic nomination, but Lichtenstein’s blessing wasn’t enough to save him from defeat at the hands of George H. W. Bush. The artist would later create an image of the Oval Office to benefit the Democratic National Committee during the successful 1992 Clinton/Gore campaign.

During his 1996 reelection effort, President Bill Clinton—always a man of the people—traveled to the Chicago Democratic convention in classic whistle-stop style—by train from West Virginia via Michigan. This art deco poster announced his arrival in the Great Lake State. It also captured his dazzling, contemporary campaign.

This modern poster for George W. Bush’s reelection bid exuded an elegant corporate simplicity. Bumper stickers with the silver “dubya” flooded the nation. At a time when terrorism and the Iraq War weighed heavily on voters’ minds, Bush used both television and print ads to tout himself as a steady leader during difficult times.

Hillary Clinton didn’t do much to win over the art crowd in 2008, and her campaign made little use of posters to secure the nomination. But her website did sell several eye-popping heavy stock posters to her fans. This one was created by Tony Puryear, a Los Angeles writer and artist.

Obama—then soon to be the nation’s first black president—inspired an artistic wave rivaling that of the McCarthy-McGovern era. Wert writes that Obama broke the so-called McGovern rule: “that cool innovative posters guaranteed a loss.” Obama not only had the support of artists; he had an adept marketing team that tightly controlled his image. Team Obama also created the iconic “O” logo and commissioned Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster—which would get the artist in trouble over photo copyright issues. In this lesser-known print, artist Ron English superimposed a map of the Midwest onto a hybrid image of Obama and Lincoln. The result: “Abraham Obama.”

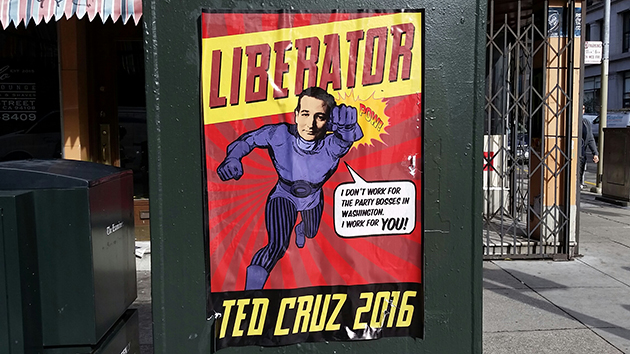

By 2012, the Obama art boom had largely petered out, but if Bernie Sanders proves a serious contender, all bets could be off. Apparently, a few artists even have an unlikely thing for Ted Cruz—although you won’t find ’em in the book…

Artist unknown.