Erik Pendzich/ZUMA

Football season is rapidly approaching and former San Francisco 49er Colin Kaepernick is still out of a job. Kaepernick, who made headlines last year with his refusal to stand for the National Anthem in protest of police brutality, has inspired a host of players—from Marshawn Lynch to various members of the Cleveland Browns to several of his old San Francisco teammates—to follow in his footsteps. But his stand is also almost certainly the reason he’s unemployed. The quarterback says he’s still working out daily in hopes of signing with a team, but, in the meantime, he’s not giving up on his activism—which, it seems, has been influenced by a legacy of black feminists.

This week, Ameer Hasan Loggins, a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley, published a column on The Athletic about his relationship with the former football star and what the public generally misunderstands about how he came into his politics. While still with the 49ers, Loggins met Kaepernick through the quarterback’s partner, New York City radio host and Cal alum Nessa Diab, and Kaepernick started auditing Loggins’ lectures at Berkeley on race and representation. “When I talk to my students about Colin, I always emphasize that when he audited my course, he (driving from San Jose to Berkeley) had his ass in class on time, everyday, taking notes, doing the readings and participating in class discussions,” Loggins writes.

Kaepernick and Loggins have also become friends, and Loggins has lectured across the country at Kaepernick’s day-long camps dubbed “Know Your Rights”—paid for entirely by Kaepernick—that bring black and brown youth together to learn financial planning, nutrition, team-building, and how to handle interactions with police. The camps so far have taken place in Oakland, Harlem (where I attended one), and Chicago.

One of the most interesting tidbits from Loggins’ piece is the reading list that he sent Kaepernick more than a year ago. There were the typical titles associated with black political thought, including Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Then, more surprisingly, there were a number of black feminist works more commonly associated with the emerging idea of “intersectionality” in contemporary black organizing, including Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment, by Patricia Hill Collins and Black Looks: Race and Representation, by bell hooks.

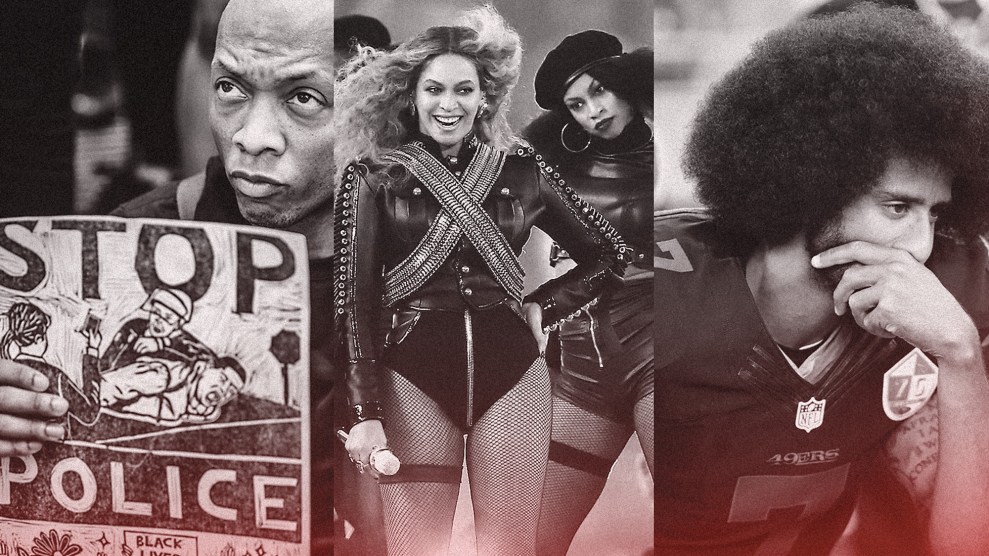

Both Collins and hooks are pioneering minds of black feminism, and their work has taken on renewed significance in recent years as a younger generation of black organizers associated with the Black Lives Matter National Network and #SayHerName have pushed back against the male-dominant tendencies of previous activist movements. The movement at large has based much of its activism around the idea that women’s labor is important, and often unrecognized. While these theoretical contributions aren’t directly linked to the activism that’s popped up in recent years, they’re definitely strong influences. The significance of this shift was articulated early on in the emergence of Black Lives Matter movement. For instance, back in 2014, Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza wrote for the Feminist Wire, “Straight men, unintentionally or intentionally, have taken the work of queer Black women and erased our contributions.”

So, is Kaepernick an avowed black feminist? It’s not totally clear from Loggins’ column or Kaepernick’s statements. But the importance of just his engagement with black feminist work can’t be understated. Not too long ago, Kaepernick was one of the NFL’s most marketable players, with high-profile endorsements from the likes of Nike and Beats by Dre. His jersey is still among the league’s bestselling. Quarterback gig or no, Kaepernick is still one of the most well-known football players in the world—and he’s still breaking barriers in a league that is arguably one of the penultimate expressions of brute American masculinity.