Mara Altman

“I am a bearded lady,” writer Mara Altman confesses in her new illustrated essay collection Gross Anatomy: Dispatches From the Front (and Back). That may elicit snickers, but Altman’s aim is to upend stigmas around our bodily realities: “It is my hope that by holding up a magnifying glass to our beliefs, practices, and nipples, this book might serve as a small step toward replacing self-flagellation with awe.”

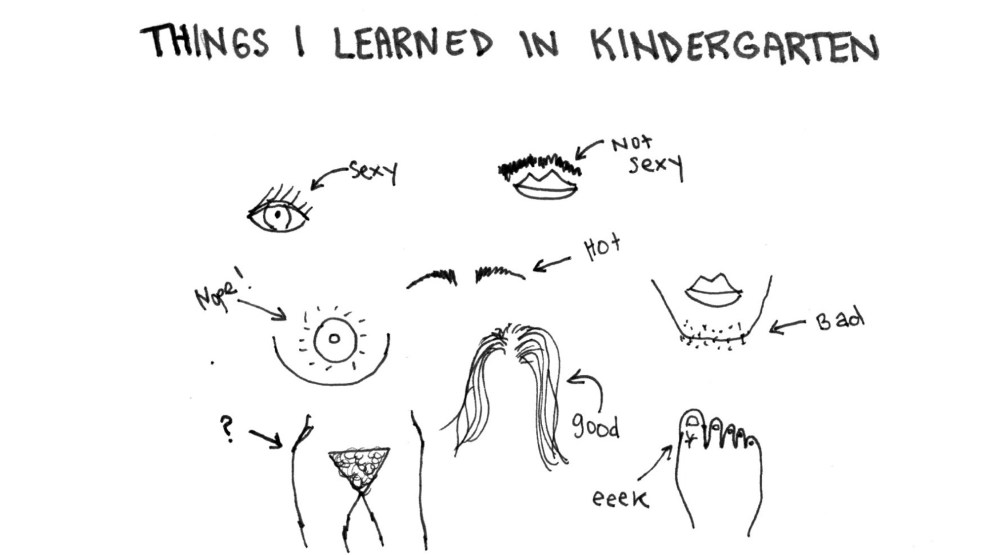

Author of the 2009 memoir Thanks for Coming, which followed a 26-year-old Altman’s quest for an orgasm, Altman attributes her fascination with bodies to her very not body-conscious hippie parents: “Growing up, I had a different concept of femininity,” she writes. “I came to think that artificially enhancing my appearance in any way showed a lack of self-acceptance, that it meant I wasn’t strong enough to be who I really was.”

In Gross Anatomy, out August 21, she traverses the body part by part, weaving together memoir, science, and psychology with self-deprecating humor in an attempt to challenge our negative connotations with our body parts and functions. As it turns out, Altman discovers, many of these associations make even less sense when you learn about their historical roots:

Body hair

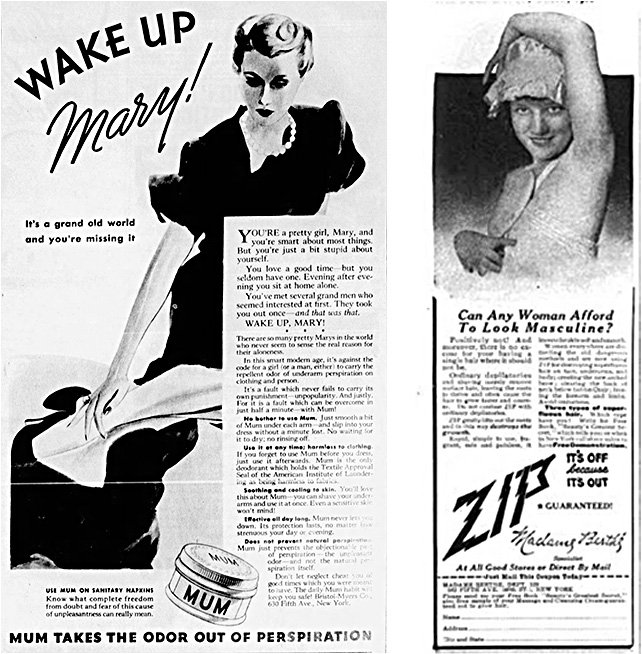

Women’s hair removal became a thing in America in the early 1900s, when women’s fashion started to show more skin—and hair. Advertisers targeted underarms first, and then legs, portraying body hair as unfeminine. A 1922 ad for a depilatory asked, “Can any woman afford to look masculine? Positively not!” Some women even exposed themselves to harmful X-rays to remove unwanted hair, a level of dedication Altman admits she “kind of admired.” Penn State anthropology professor Nina Jablonski told Altman that hairlessness has been viewed as desirable since ancient times because of its association with youth, and thus with fertility.

In fact: There’s no benefit to removing body hair unless, perhaps, you’re an Olympic swimmer. In fact, keeping it actually has its advantages: Des Tobin, a cell biology professor at the University of Bradford, told the Daily Mail that body hair can help skin heal from a wound—as hair follicles are full of stem cells—and also provides a modicum of warmth and sun protection.

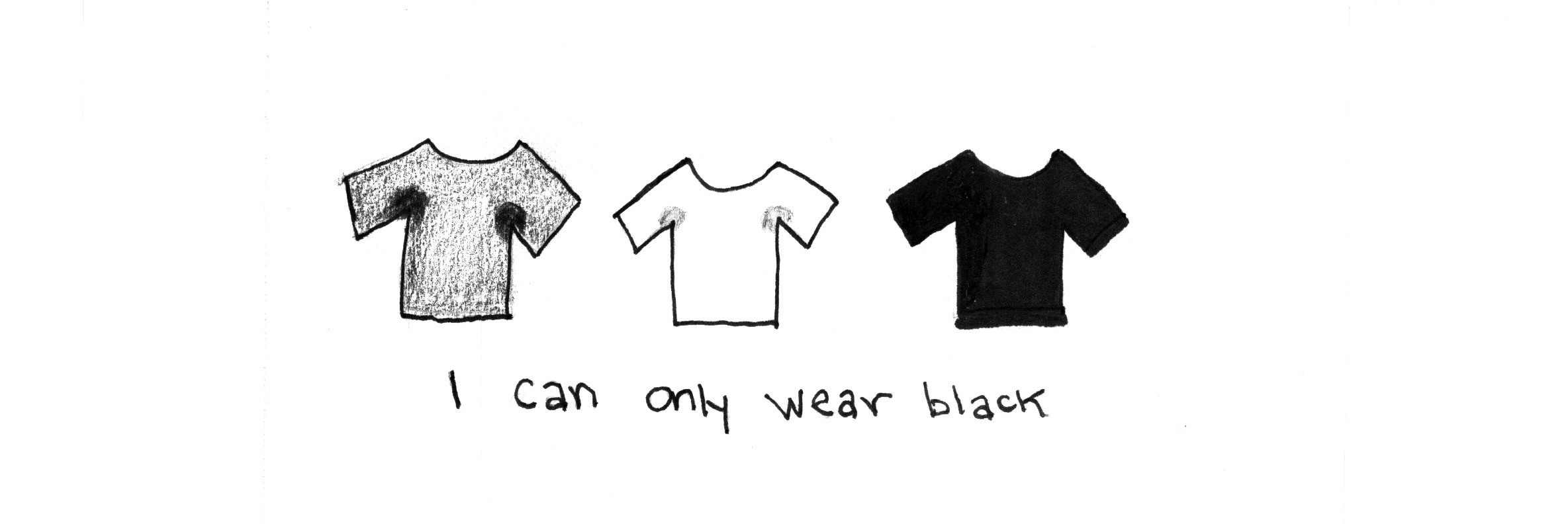

Sweat

From 1500 to 1800, Altman writes, people believed clogged sweat glands could kill you. They also thought sweat was a conduit for releasing gunk from the body—a dangerous, disease-ridden fluid. By the early 1900s, advertisers were exploiting this fear to sell antiperspirant. “You’re a pretty girl, Mary, and you’re smart about most things. But you’re just a bit stupid about yourself,” reads an ad showing a despondent young woman. “You’ve met several grand men who seemed interested at first. They took you out once—and that was that. WAKE UP, MARY!”

In fact: Daniel Lieberman, a sweat expert at Harvard University, tells Altman that mammals first started to sweat from their paws millions of years ago to help them survive: Sweat created traction so the creatures could climb and escape from predators. Eventually, its purpose evolved to regulate body temperature. And contrary to popular belief, sweat doesn’t purge the body of toxins. So much for hot yoga sessions.

Vaginal odor

This was not a big concern for women in the Middle Ages: “They had bigger things to worry about, like the plague,” Altman writes. And although women douched with a variety of substances (often wine), they did so hoping to ward off disease. It wasn’t until the 19th century that douching was promoted by a physician named Charles Knowlton as birth control. After Congress passed a strict law regulating dissemination of information about contraceptives in 1873, douching was rebranded as “feminine hygiene,” and marketers set about making women self-conscious about their scents, with ad copy like, “Unfortunately, the trickiest deodorant problem a girl has isn’t under her pretty little arms” and, “The world’s costliest perfumes are worthless—unless you’re sure of your own natural fragrance.”

In fact: Brown University professor Rachel Herz points out to Altman that humans are born with a blank sense of smell, thus negative connotation with vaginal scent is nurture, not nature. Gordon Gallup, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Albany, even draws an evolutionary connection, citing studies that say men are likely more attracted to a woman’s scent when she’s ovulating, and therefore more game to get it on.

Illustrations by Mara Altman