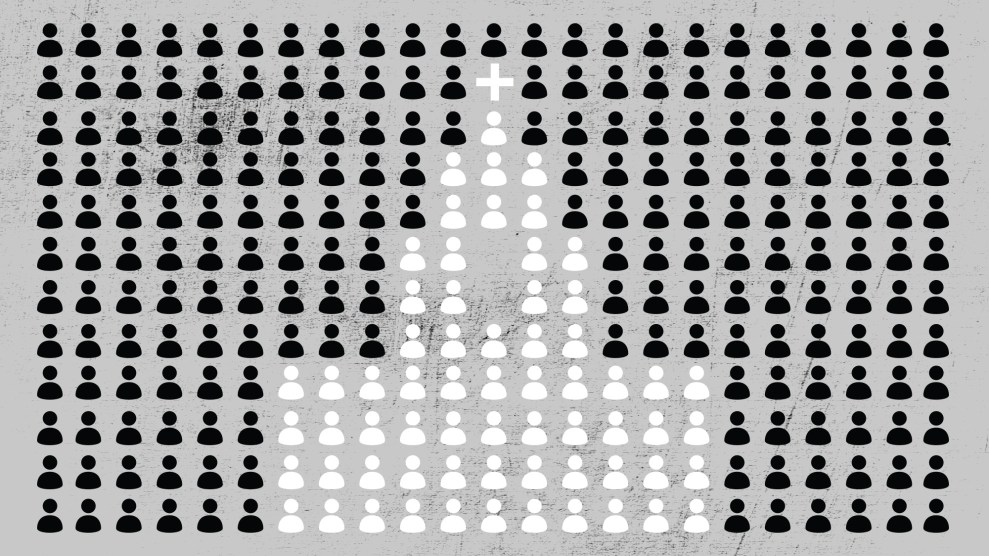

Mother Jones illustration

A month before her church’s vacation bible school started, Kristen Koger, a pastor at First Baptist Church in the Atlanta-adjacent city of Decatur, Georgia, found herself scrambling to change the lesson plans. The curriculum her church had recently purchased was the target of an onslaught of criticism over an exercise instructing students to role-play as “Israelite slaves” while the teacher acted as a “mean Egyptian guard.”

The Africa-themed curriculum, titled “Roar,” also had students mimic the Xhosa language; students were told to try adding clicks to their names to mimic the language. In one instance, Africa was referred to as a country.

During the role-playing exercise, the curriculum instructed students to build bricks using mud and straw included in the program kit while the teacher walked around the room pressuring students to work harder. The script instructed the teacher to refer to the kids as “a bunch of lazy slaves.”

In this lesson, the teacher is supposed to set up a pretend scenario in which the kids play being slaves while the adult berates them. pic.twitter.com/ytMgeBEcPh

— Shannon Dingle (@ShannonDingle) June 7, 2019

The curriculum was created by Group Publishing, one of the biggest Christian publishing companies in the country. The company has since updated the lesson plan and got rid of the controversial role-playing exercise, which they said was meant to engage with the story of Moses and the Israelites’ escape from Egypt. They also changed the lesson on the Xhosa language. A few days after the criticism, Group posted an apology on its Facebook page with a link to download the revised exercises.

“The intent was for children to experience the biblical story and appreciate how horribly the captive Israelites were treated under the Pharaoh,” Group president Thom Schultz said in a statement. “We understand the concern, and we apologize for the insensitivities.”

The revisions excluded the exercise mimicking the Xhosa language; instead the students watch a video about it. It also includes changes to the role-playing exercise: Instead of explicitly instructing the students to pretend to be slaves and build mud bricks, the new lesson walks students through a series of physical exercises like jumping jacks, running in place, and carrying heavy books to highlight hard work.

Despite these revisions, the incident has sparked conversation among church leaders about the lack of diversity both within the publishing company and among those writing and editing youth programs. According to Schultz, the Group’s staff reflects the community of Loveland, Colorado, where the company is based. The company is roughly 84 percent white, he said.

“There’s such a distinct chasm between people who make curriculums and the actual churches that they will be serving,” said Sunny Brown, founder and CEO of Church Youth Matters, a training program for youth pastors in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Brown stopped using Group’s VBS curriculum while working as a youth pastor in Brooklyn. She said there were cultural references throughout the lesson plans that weren’t connecting with her students. She remembers going through lessons that referenced visiting a summer vacation house, a boating trip, or other cultural touchstones that weren’t resonating with her students in New York.

“Once we normalize diversity, that’s real reconciliation,” she said. “We’re just not seeing yet. Group brought that to the forefront.”

Reaching more than three million kids every summer, Group publishes everything from VBS and Sunday school lessons to bibles and sermons. Brown remembers growing up with Group’s lesson plans in her church. For VBS, the options are limited, she said, leaving church leaders with only a few options for their students. Often, those options aren’t sensitive to the needs of different groups.

“If I want my curriculum to go to a particular group or area, then I need to make some adjustments because I don’t want to traumatize them,” she said. Brown no longer uses Group’s programs. She praises the work of Urban Ministries, Inc., an African American Christian publishing company that she said more explicitly highlights a diverse group of kids in their lesson plans and promotional materials.

VBS programs are often free or cheap—Koger’s church in Decatur charges $25 per student for the program—childcare during the summer months. Often, this attracts a more diverse group of kids who may not necessarily be part of the church community.

“Vacation bible school is probably the most diverse thing we have all year,” said Tandy Adams, director of family ministries at Castleton United Methodist Church in Indianapolis.

Adams has been using Group’s curriculums for years. In her 30 years in the ministry, she’s seen Group become a trusted source for youth programs because their lesson plans are often easy to adapt to different sects of Christianity. Group also provides decorations and supplies. But since the Roar curriculum has come out, she doesn’t know if she’ll use Group’s lesson plans again. She and her team rewrote parts of the program days before their VBS was set to start. They also left out several of the videos included in the program. But she acknowledges that many churches don’t have the resources or the capacity to rework the lesson plans.

The basic “Roar” curriculum kit starts at $184.99, and churches can buy separate supplies for each exercise, which cost from $52.99 to $589.99 depending on the size of the classroom. There’s no way to know exactly what the lesson plans look like before purchase. Group offers a brief overview of the program, but the scripts, exercises and videos are off limits.

“These VBS programs aren’t cheap,” Adams said. “When you buy them, you’re really buying them on good faith.” She said she and her team are working on compiling their revisions and sharing them with other churches that need them.

Koger said she thinks about who’s attending her VBS programs when she prepares for the summer. Even if they’re not church-goers, Koger’s goal is to ensure that every student in their VBS program feels safe in the church. A month before VBS started, Koger decided to not use the “Roar” curriculum losing thousand of dollars that had been invested into preparing for the summer.

“We didn’t want to be connected or associated with a curriculum that may or may not be racist,” Koger said. She doesn’t plan on using Group’s curricula in the future. “They broke my trust as a pastor,” she said.

Adams was one of the first to contact Group via a private message on Facebook. The company responded with a “stock answer,” she said, that tried to justify the lessons: “Experiential learning helps kids develop empathy,” they wrote. After screenshots of those messages were shared on Twitter, Group published an updated version of the curriculum without those two lessons and issued an apology.

Schultz said the program was created by a group of three staff members, none of whom were black. The staffers traveled to Africa and consulted with teachers before writing the curriculum. It was also tested with thousands of religious groups, and children who gave them feedback on the curriculum. “After all that, unfortunately, we all missed some problems,” he wrote in an email to Mother Jones.

“In these days of divisiveness, we are increasingly aware of the need for cultural sensitivity and racial reconciliation,” Schultz said. “We are committed to redouble our efforts in future programs to create and vet materials that are inclusive, respectful, loving, and focused on Jesus.”

Moving forward, the company is planning on diversifying its writing team and creating “an additional advisory group to help with cultural sensitivities,” Schutz wrote.

Brown, Adams, and other clergy didn’t think Group’s revisions went far enough. Ultimately, Brown said, the problem lies in Group’s mostly-white team writing an Africa-themed curriculum. For her, the problem won’t be fully solved until Group makes the effort to intentionally include people of color.

“This is the exact reason why Sundays are the most segregated day of the week,” she said.