Participants hold signs with the Puerto Rico's flag painted in black and white as symbol of resistance and civil disobedience during the NYC's 60th annual Puerto Rico Day parade on June 11, 2017 in New York City. Maite H. Mateo/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images)

Just past 2:00 a.m. on July 4, 2016, four women arrived in front of a rustic wooden door in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. For years, the door located at 55 Calle San José displayed a mural depicting the Puerto Rican flag: a bright sky blue triangle hugging a white star layered over bands of red and white. It had become one of the most recognizable and visible sites in San Juan, serving as a popular backdrop for vacation photos and selfies for tourists and locals alike.

But the women felt the door needed an update. It was the United States’ Independence Day, but the artists were in no mood to celebrate. Four days prior, then-President Barack Obama had signed into law the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which imposed a seven-member fiscal control board responsible for managing the island’s $123 billion debt. The board, which is comprised of people who were neither elected nor living in Puerto Rico, was given supremacy over the island’s laws and decision making—a move many condemned as an act of colonialism.

The four women, who are part of an anonymous artist collective that came to be known as La Puerta, identified with a movement calling for Puerto Rico’s independence from the United States. Armed with cans of spray paint and rolls of tape, lit only by the glow of streetlights, they blackened the flag’s blue triangle and red stripes.

Pintaron bandera negra de la puerta Calle San Jose en Viejo San Juan ¿algún voluntario? Para devolver el color 🇵🇷 pic.twitter.com/jufOKvvFVw

— VR (@vincentrivera) July 5, 2016

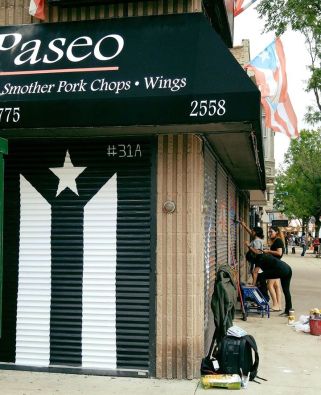

Three years later, the image of Puerto Rico’s black and white Resistance flag, as it’s come to be known, has spread far outside the confines of Old San Juan. Activists fly it at protests around the United States. Murals of it can be seen on the streets of Chicago. Replicas can be found on T-shirts and coffee mugs at souvenir shops throughout the island. When season 2 of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It premiered on Netflix last May, you could see the flag on the wall behind the characters in a scene depicting a Hurricane Maria benefit performance.

The black-and-white banner is especially noticeable given that Puerto Ricans are notorious in Latinx circles for being extra proud of their flag. Memes that circulate during the National Puerto Rican Day Parade in New York City every June often poke fun at this admiration; a popular one shows a Puerto Rican man dressed in flags with the caption “How did you know I was Puerto Rican?” written across the top. On the West Side of Chicago, the steel Puerto Rican flags that welcome visitors at each entrance of Paseo Boricua, the city’s historic Puerto Rican district, are a full 59-feet tall.

Absolutely no one:

Puerto Ricans: pic.twitter.com/Fa9ev7rhrn

— pollito🐣 (@rubydrummr) June 14, 2019

While it’s easy to dismiss this love as braggadocious nationalism, a quick look into the history of flags in Puerto Rico reveals a much more complicated story. The flag is not only a symbol of affirmation, “it is used as a symbol of resistance to colonialism,” explains Jorell A. Melendez-Badillo, a historian of Latin America and the Caribbean at Dartmouth College. He points to the island’s first flag, the Revolutionary Flag of Lares, which was designed ahead of a major uprising in Lares, Puerto Rico, in 1868 against the island’s first colonizer, Spain.

The Revolutionary Flag of Lares.

Wikimedia Commons

What would later become the territory’s official flag was created in the 1890s by pro-independence Puerto Ricans in New York City and took inspiration from Cuba’s banner. In a sense, Melendez-Badillo says, this flag symbolized a future where Puerto Rico would one day become a sovereign nation, free from colonial rule. While Puerto Rico would indeed break free from Spanish rule, its independence would never materialize. In 1898, the US invaded, passing the island from one imperial ruler to another.

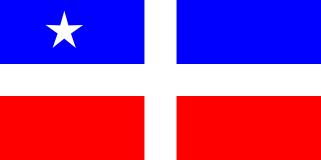

The original design of the Puerto Rican flag.

Wikimedia Commons

In the mid-1900s, another pro-independence movement was gaining steam, this time against US control of the island. The red, white, and sky-blue flag became one of the coalition’s unifying symbols. In an effort to diminish the movement, Puerto Rico’s US-appointed legislature passed La Ley de la Mordaza, or the Gag Law, in 1948, which made displaying a Puerto Rican flag punishable by up to 10 years in prison. By making the flag illegal*, Melendez-Badillo says, the state also inadvertently radicalized it, positioning the flag in the Puerto Rican imagination as a symbol that represents the people’s constant fight for freedom.

While the Gag Law would eventually be deemed unconstitutional, the insular government found a way to successfully strip the flag of its radical meaning. In 1952, the commonwealth government adopted the pro-independence flag as the official flag of Puerto Rico, changing its sky blue to navy blue so that it resembled the United States’ flag, and stripping it of its revolutionary past.

When La Puerta repainted the flag black and white, Melendez-Badillo says, it was “a way of re-radicalizing the concept of the Puerto Rican flag.” After the women repainted the door, they released a letter explaining that the flag was meant to represent resistance to US-imposed austerity measures and colonialism. Soon, the Resistance flag moved from the door on 55 Calle San José to the streets of Puerto Rico and the United States. Versions of the flag began popping up in murals throughout the country. Student groups incorporated it into their protests of budget cuts to the island’s public institutions.

A mural in Chicago’s Paseo Boricua displays Puerto Rico’s black-and-white Resistance flag.

Miguel Alvelo / Chicago Boricua Resistance

On May Day 2018, people gathered in San Juan to protest the fiscal control board’s strict austerity measures. The demonstration quickly turned violent. Amid the chaos, the black-and-white flag could be seen waving high in a cloud of tear gas and painted on the long wooden shields people used to protect themselves.

Today, many Puerto Ricans feel suffocated by the island’s social and economic crisis. The population is rapidly dwindling, schools are closing en masse, entire communities have no access to hospitals, and 44 percent of people live in poverty.

“We gave young people who don’t identify at all with any political party and who don’t see a bright future for Puerto Rico a symbol of hope,” one of the La Puerta artists, who asked to remain anonymous, told me. “It is a symbol that unifies us no matter what.”

Melendez-Badillo thinks the flag will continue to have a special currency. “In Puerto Rico, we’re always imagining this potential nation,” he said. “Flags come to represent other things. They come to represent a potential future that has not been attained.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the period of time that the flag was considered illegal.