Inside a serene natural grocery store in Mill Valley, California, Dr. Jen Gunter is scowling at the women’s health aisle. “What’s wrong with the way the vagina smells?” she scoffs, looking over the topical wipes, creams, and washes promising to resolve undesired aromas. “There are no products here to make balls smell better.”

Gunter whips out a pair of tortoiseshell glasses to read the fine print on a tube labeled Good Clean Love pH Balancing & Moisturizing Vaginal Gel ($18.19), which promises to “naturally eliminate feminine odors.” “You don’t need any special wash,” she says. And don’t waste your money on cleansing wipes—“totally scammy.”

“All these things are designed to tell you that your crotch stinks,” she says. “I hate it.”

As an OB-GYN with nearly three decades of experience, Gunter knows from crotches. And today she is angry about how certain products—“vaginal offenders”—are pitched at women. “Since the beginning of time, women have been told that they are dirty,” she says. “They want us to be ‘pure,’ they want us to be ‘clean.’ These words have been weaponized.” And shaky assertions made by natural health products serve only to misdirect women, Gunter argues in her new book, The Vagina Bible: The Vulva and the Vagina—Separating the Myth From the Medicine, a sassy manual of anatomy and self-care tips. If a topical product claims it can regulate pH, she writes, “I always wonder: What other false claims are they making?”

We wander toward the soap aisle. At 5 feet 10 inches—even if you don’t count her 2.5-inch blue leather heels—Gunter towers above me, her honey-blond curls spilling out over the collar of a puffy jacket. She eyes a bar made with activated charcoal, a trendy ingredient she deems pointless. “Why get upset about a useless product?” Gunter says. “Because it makes everybody stupider—facts matter.”

As the global wellness industry tops $4.2 trillion, Gunter, 53, is on a mission to arm women with science-based advice in hopes of stanching the spread of health misinformation. Increasingly, she’s been sounding the alarm about how confusion surrounding women’s bodies fuels larger efforts to control them. In recent months, conservative lawmakers in states like Alabama and Missouri have passed harsh restrictions on abortion based on flawed understandings of the female reproductive system. “I’ve been swatting at pseudoscience for so many years, I have the language to tackle it,” Gunter says. “People are listening now, so I have a duty to step up.”

Raised in Winnipeg, Gunter now lives and practices medicine in the Bay Area. You may recognize her name from her eponymous blog (tagline: “Wielding the lasso of truth”); her New York Times column The Cycle; or her extremely active Twitter presence (pinned tweet: “Come for the sex, stay for the science”). She also has a new TV series, Jensplaining, on the Canadian streaming service Gem, devoted to demystifying misperceptions around health trends. She’s probably best known, though, as a fierce critic of Gwyneth Paltrow’s $250 million wellness empire, Goop.

Back in 2015, a friend of Gunter sent her an article published by a doctor on Goop’s website that suggested women who wear underwire bras should be concerned about getting breast cancer, in part because bras supposedly impede lymphatic flow. “You’re a site that’s supposed to empower women, and you’re spreading this myth?” Gunter thought at the time. She quickly posted a critique on her own blog, pointing to the fact (echoed by the American Cancer Society) that no credible studies have ever established such a link, “never mind that the mechanism is biologically implausible.”

A few months later, Paltrow made national headlines after touting the benefits of an LA spa’s “V Steam” in a Goop review: “You sit on what is essentially a mini-throne, and a combination of infrared and mugwort steam cleanses your uterus, et al. It is an energetic release—not just a steam douche—that balances female hormone levels.” Gunter spotted the story at 6 a.m. The review was offensive to her on many levels, including the way it played into so many “patriarchal myths of women being dirty.” She fired off a post in response, pointing out that the vagina and uterus are “self-cleaning ovens,” and that steam may actually do more harm than good. The post took off. (Goop’s review no longer makes mention of the uterus or hormones.)

Soon Gunter’s Goop criticism became a regular feature. Sometimes the posts went viral, as with a scathing takedown of Goop’s $66 jade “yoni” eggs, said to increase “vaginal muscle tone” and “hormonal balance.” The critiques gave Gunter a chance to poke holes in a celebrity’s bubble of influence. Paltrow “mentions a trend, and a lot of people might try it at home,” she told Kara Swisher in an interview on the podcast Recode Decode.

In May 2017, Gunter wrote a more sweeping condemnation of Paltrow’s site, calling it a “scare factory.” The post seemed to hit a nerve. For the first time, Goop’s editorial board responded with a post of their own, alluding to Gunter as one of the “third parties who critique goop to…bring attention to themselves.” The article goes on to call Gunter “strangely confident,” and then hands the microphone over to a physician who defends his own clinical expertise while also devoting a large amount of real estate to Gunter’s use of the “F-Bomb.”

Gunter responded, calling herself “appropriately confident, because I am the expert,” and several scientists and doctors chimed in to defend her. Goop’s diatribe “is the equivalent of the Trump administration trying to point fingers at the [leakers] in order to divert attention from the information contained in the leaks,” wrote Dr. Steven Novella, author of The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe.

Gwyneth Paltrow’s empire now includes a wellness summit, “In Goop Health.”

Goop

But sweeter revenge came in September 2018, when Goop was forced to pay $145,000 in civil penalties to settle a consumer protection lawsuit brought by prosecutors in 10 California counties over three of its products, including its jade and rose quartz vaginal eggs. “People have been selling snake oil for a long time. This is just another type of snake oil,” then–Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas told CBS News. Goop denied any wrongdoing, and the products remained on the site, though their descriptions were changed. (The company now employs a fact-checker.) Still, Canadian health law and policy professor Timothy Caulfield, author of the book Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything?, said the settlement sent “a powerful message” about the type of information found on sites like Goop, calling it “a little victory for science.”

A month later, Gunter published a study in the journal Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery taking aim at a different Goop claim made about the jade eggs: that they were used in ancient Chinese culture by queens and concubines to “stay in shape for emperors.” For the study, Gunter and archaeologist Sarah Parcak analyzed online archives of 5,000 objects in four major Chinese art and archaeology collections and found no evidence of vaginal eggs ever being used or recommended.

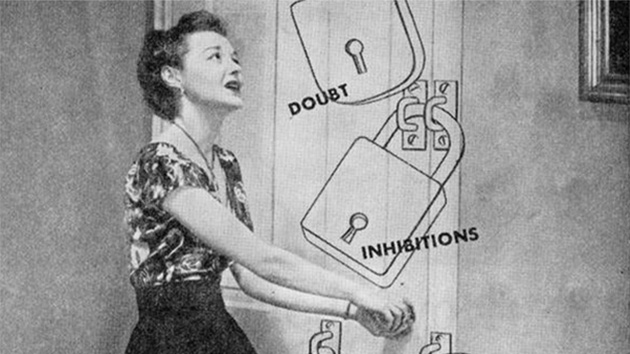

Gunter isn’t just hunting bunkum for personal satisfaction. As she sees it, steam douches and cleansing wipes and quartz eggs have roots in the dominion that’s long been extended over women’s bodies. In the era of Hippocrates, perfumes and scents were applied to control the uterus, which was thought to wander. In 1950s America, Lysol scolded women for “intimate neglect” and faulted them for cooling marriages. “One most effective way to safeguard her dainty feminine allure is by practicing complete feminine hygiene” with Lysol douches, promised one advertisement.

According to Chris Bobel, a professor of women’s and sexuality studies at University of Massachusetts–Boston, women are viewed as dirty and impure from the day they first get their periods. “We begin with very early messages about how your body is a problem to be solved,” Bobel says, “and that sets up a constant quest to fix it.” They’re also told to stay pure in a sexual sense. In a world where men are in charge, these notions help dissociate women from their bodies, which are seen as valuable only to the extent they can serve as instruments for the larger good.

Many of our elected leaders would prefer to keep things that way. In the first six months of 2019, US legislators introduced 378 new abortion restrictions across the country. Many of them ban abortion after six weeks, or before many women know they are pregnant. Gunter sees parallels in how the wellness industry and conservative legislators capitalize on stigma and confusion to try to control women. “It’s all the same tactics, it’s all the same shell game,” she says. As she sees it, the wellness industry is using pseudoscience against women to take their money, and the anti-abortion set is using pseudoscience against women to take their power. And Gunter considers herself uniquely qualified to tackle the lies of either group.

In 2017, more than half of US women of childbearing age lived in states with abortion restrictions that conflict with scientific evidence. This misuse of science “isn’t something that’s going away,” says Elizabeth Nash, the Guttmacher Institute’s senior state issues manager.

Gunter has increasingly drawn on her expertise as an OB-GYN to speak out against “medically illiterate” laws. Activity in the fetal pole, a thickening at the edge of an embryonic egg sac, should not be described as a “heartbeat,” she argues in one post, addressing the flurry of “heartbeat bills” that seek to ban abortion as early as six weeks into pregnancy. In early June, the Guardian updated its style guide to no longer refer to the bills in such a manner; its post announcing the decision quoted Gunter and her “influential blog.”

In an op-ed published in the New York Times on May 20, Gunter invoked her experience performing abortions to argue that Alabama’s abortion law—now the strictest in the country—used vague terms to try to make medically necessary abortions harder to obtain. The law states that it allows doctors to “deliver the unborn child prematurely” to avoid a “serious health risk” to the mother, such as the risk of death or “substantial physical impairment of a major bodily function.” But the law never explicitly defines how “serious” a risk must be, nor does it clarify whether “deliver” means only an induction of labor or also a surgical abortion.

Two days after the op-ed went viral, Gunter strutted onto the stage of San Francisco’s Sydney Goldstein Theater in a red leather jacket and sequin-encrusted bell-bottoms. She was there for a live interview by the writer Ayelet Waldman as part of the popular City Arts and Lectures series. The packed audience included women of all ages, a sprinkling of men, and at least one of Gunter’s patients. After a few jokes about vaginal weightlifting, the interview took on a more somber tone. A conversation about the body in its funny particulars had become a conversation about bodily freedom. “No woman has benefited from learning less about her body,” Gunter told the audience, slowing her voice to let each word sink in. “People are writing laws that are going to affect women and gender minorities. We have to put a line in the sand and say: The truth matters.”