The artist in 2014Timothy Palmer

Back in 2013, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco invited me to contribute to a show about yoga co-organized by the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. The exhibition, Yoga: The Art of Transformation, was the first major show ever mounted about the 2,500-year history of yoga. It featured over a hundred paintings, photographs, and sculptures. Curators, seeking a contemporary perspective, invited me to contribute to an educational exhibit for the show after having met me at a previous event. At the same time, I had another project up, at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, documenting the Indian American motel community across this country. It was an exciting time for me. But I didn’t expect the absurdities that would soon follow—a parade of condescension, passive aggressiveness, and white fragility in which the Asian Art Museum revealed itself to be in a losing struggle with the whiteness at the core of its identity.

My run-in with the museum is the subject of new work I’m showing this month at the Human Resources gallery in Los Angeles. It’s taken me this long to tell the story because it was such a jarring experience. This was the Asian Art Museum, the largest museum dedicated exclusively to the Asian arts in the United States—one of the largest platforms out there for an artist like me.

When I was asked to contribute, I took the invitation at face value: The Asian Art Museum wanted to give space to an Indian American artist. Much of my work focuses on first-generation Indian American experiences with appropriation and assimilation. The museum provided a first-floor wall—a big platform and a big honor.

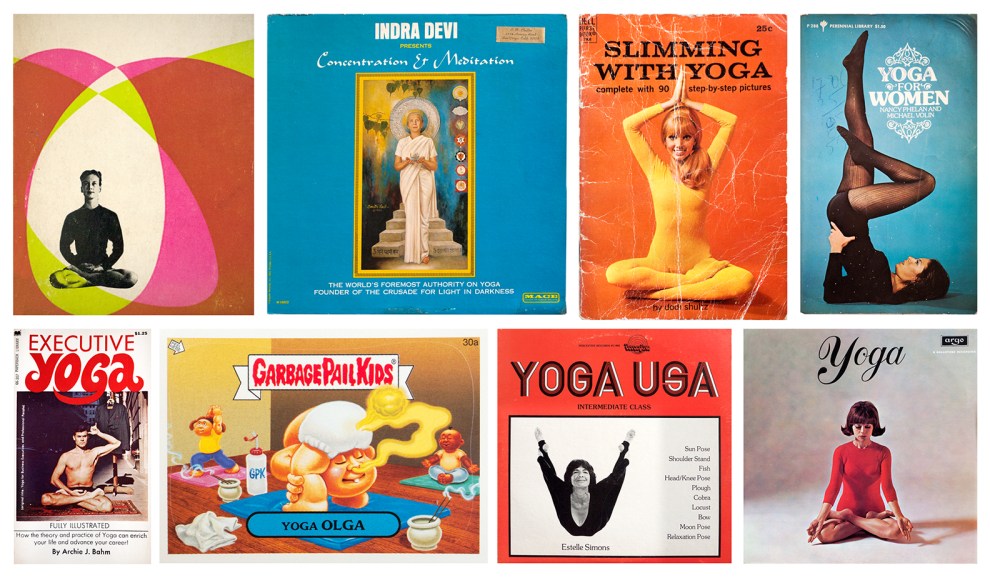

Our agreement for the installation included my assemblage of yoga ephemera that I’d collected in the form of magazines, books, posters, and album covers. Together they told the story of how the $16 billion yoga industry in this country had rebranded a South Asian discipline to sell yoga as a line of products—how yoga became Yoga™. It’s no coincidence that you rarely see a South Asian person on the cover of Yoga Journal magazine. Yoga has been put in an ironic position: Colonized and commodified, a tradition rooted in detachment and equanimity has been hijacked by a grasping possessiveness. I titled my work #WhitePeopleDoingYoga.

I knew the title #WhitePeopleDoingYoga would be provocative, but I chose it for a reason: For this installation, yoga was a case study in how culture gets colonized, a pattern that holds across industries, from fashion to food to music. The installation was meant to show how overwhelming and suffocating appropriation becomes under a capitalist structure. Every piece in the installation was either selling something or was itself once for sale.

But once my proposal made the rounds among curators, educators, and PR folks, cracks started to show in the museum’s support for the installation. The show’s lead curators and education staffers I’d met—all but one of whom were white—didn’t feel completely comfortable with the title. They wanted something innocuous like #PeopleDoingYoga, without the word “white,” because the term “white people” could be “offensive” to museumgoers, donors, and staff. During our initial meetings at the museum, they told me to “turn down the volume” of my critique. They also insisted I remove a section of the installation—a Hindu-inspired shrine featuring photographs of a white couple as South Asian gurus. “This might be offensive to Indian people,” staffers said—white authorities telling me what Indian people might find offensive. They gave me an ultimatum: Either I take down the shrine, or they don’t include my installation. Museum leaders were diluting my installation, going well beyond the standard curatorial role.

[In an email to a Mother Jones fact-checker, museum reps acknowledge that there had been misgivings over the title and the installation in general, which they emphasize was intended to be “educational” rather than artistic. But they dispute that there was any ultimatum. According to a museum spokesperson, Bhakta was told that the phrase “white people” could be “offensive or puzzling” to some. As examples, the spokesperson pointed to “Anglo practitioners of yoga unfamiliar with the concepts of cultural appropriation/appreciation, and K-12 students who haven’t had the proper exposure to understand the statement implied in ‘White People Doing Yoga.'” Additionally, in the same email to Mother Jones, Qamar Adamjee, one of the exhibit’s curators, writes that the museum objected to the shrine on the grounds that “as an object type [it] did not align with the rest of the display,” but that the installation was not contingent on its removal: “We had invited him to do the display and revoking that invitation was not a consideration at any point.”]

Over the years, I’ve heard many shocking accounts from friends—artists of color from New York to Bombay, Los Angeles to London—about their experiences with institutional racism in its various forms. The numbers alone tell some of the story: A recent Williams College study found that 75 percent of artists in major US museums are white men, and the Association of Art Museum Directors reports that 72 percent of staff at its member institutions are white. These are the people who shape and reshape the canon, who have the power to decide and dismiss.

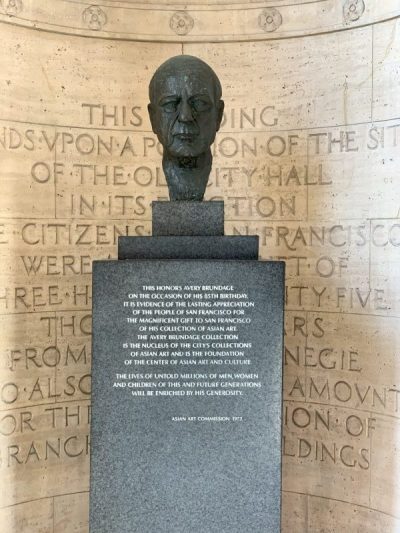

A bust of Avery Brundage at the entrance of the Asian Art Museum

Chiraag Bhakta

Consider the Asian Art Museum’s own history: It was founded on the collection of Avery Brundage, a Chicago businessman and the fifth president of the International Olympic Committee. Brundage’s portrait still hangs proudly in the museum library; a bust of him greets you at the entrance of the museum. In 1959, Brundage began donating his Asian artwork to the city of San Francisco—a collection that would amount to nearly 8,000 pieces. What the museum leaves out of its public narrative is that its founder was “the preeminent American apologist for Nazi Germany,” in the words of author Jeremy Schaap. In the ’60s, the Olympic Committee for Human Rights, a group protesting racism in sports, demanded Brundage’s removal as the Olympics president. The committee had exposed his ownership of a country club in California that excluded Jewish and black people from its membership. In response to a potential boycott by black athletes of the 1968 Olympics, Brundage notoriously said, “They won’t be missed.” (He had been instrumental in preventing a US boycott of the so-called Nazi games in 1936.) Brundage was “a racist down to his toes,” said Lee Evans, an American sprinter on the 1968 Olympic team. “A brutal, racist pig,” said a teammate, Marty Liquori. A “Jew hater and a Jew baiter,” was the verdict of Gustavus Town Kirby, delivered in a 1936 letter to Brundage himself. Now think about how a man like this actually acquired his art collection. Don’t fool yourself.

The Asian Art Museum is far from the only institution negotiating its own white supremacist foundations. Just a few years ago, the British Museum’s Twitter account revealed as much when it shared how it decides to label artwork, tweeting: “We aim to be understandable by 16 year olds. Sometimes Asian names can be confusing, so we have to be careful about using too many.” (Dang, sorry to all those 16-year-old Asian kids with funny names.)

My installation went up after rounds of hard-fought revisions. I stood firm on the title #WhitePeopleDoingYoga, but I caved on the museum’s ultimatum: I took down the shrine depicting a white couple as South Asian gurus.

The installation as it appeared at the Asian Art Museum

Chiraag Bhakta

Let’s break this shit down: Here were white elites exerting power over Brown critique that was explicitly about white elites exerting power over Brown culture. The irony is comical now, but it was painful and unnerving then. After taking parts down, I thought the worst was over, but it was only the beginning. People across the operation, from the marketing department to the education team to the curatorial staff, continued to sterilize my perspective, tiptoeing around me to make themselves feel more comfortable and spare the museum further controversy. Brown critique had to be sanitized for white consumption.

Throughout my meetings with curators and educators, there was one person whose name they kept mentioning as an authority calling the shots—the chief curator, also white, an unseen figure in the forest who seemed to be deliberately keeping a distance. At first, I wouldn’t have expected the chief curator to get involved, but it was a bit alarming that he never did, given all that went down. Some of the staffers under him were maneuvering through tense conversations with me, like messengers nervously doing their boss’s bidding to keep their jobs. I completely sympathize, but it left me wondering: Was I seeing the museum’s disorganization or something more malicious, a deliberate mixing of messages? It felt as if I’d hit a sore spot with several white staffers. Some of them had dedicated their entire lives to Asian arts, and now they had been implicated in my critique of appropriation. Why were they being criticized, they seemed to wonder. Weren’t they the ones giving nonwhite artists like me a platform?

I’d soon caught wind that senior staffers, without telling me, had decided to withhold my work’s title from marketing material. This was enraging. The title #WhitePeopleDoingYoga was my observation—my statement as an Indian American. It was the core of my piece; the ephemera was just the vehicle, and the museum knew that. This battle over a title became a proxy for something bigger: a struggle over whose sensitivities needed to be protected and whose could be ignored.

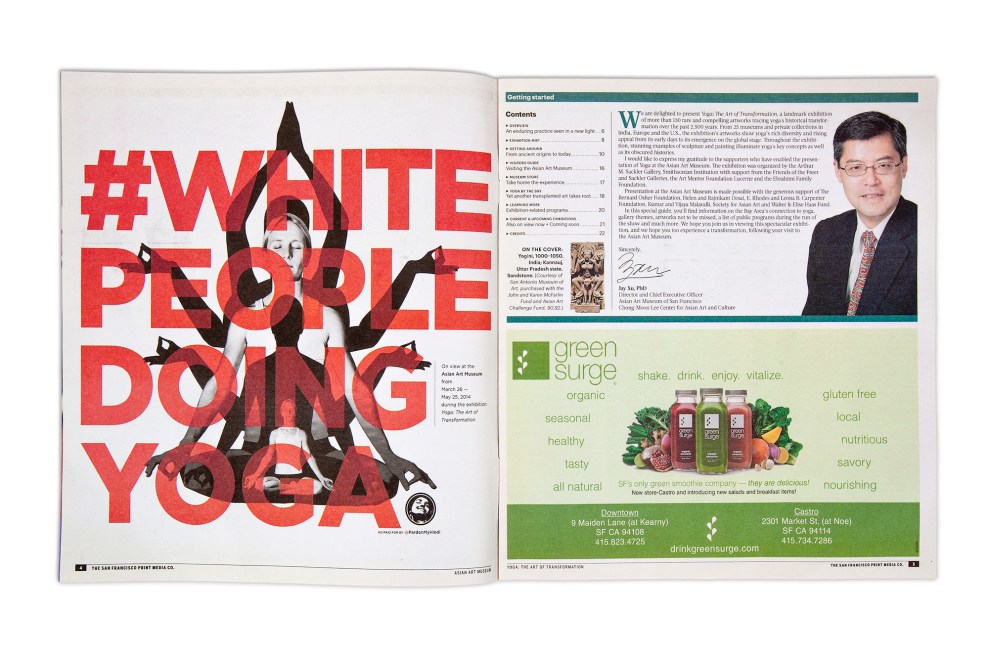

As part of the marketing rollout for the yoga show, the museum planned to publish a 12-by-12-inch, 24-page advertising supplement in the San Francisco Examiner, the SF Weekly, and the SF Bay Guardian. In all, 250,000 copies were being printed. The museum had decided behind my back that it was not going to promote my work in an honest way—not just by excluding the title but also by dumbing down the description of my work. At one point, a draft of the marketing material referred to my work as an “amusing” and “lighthearted” collection.

And of course my title was nowhere to be found in the supplement. I decided to insert it myself: I contacted the supplement’s ad team, without consulting the museum, and took out my own full-page ad:

I paid out of pocket, negotiating a reduced rate that was equal to what the museum had paid me for my installation: $1,500. Straight into my hands for my work and straight out of my hands for my ad, all to retain my voice. Symmetry at its finest.

By this point, the museum store had already agreed to sell merch that I would create: T-shirts, tote bags, and postcards. (Ah, the irony of selling products for an installation critiquing capitalism.) When it came time to display my merch in the store, the marketing chief found out that my stuff bore the title #WhitePeopleDoingYoga and froze: In a meeting with two PR leaders, the marketer told me in a chipper, condescending voice that they weren’t sure where they stood on my merch. They needed a few days to think it through while keeping all the products in the basement.

I called a meeting, inviting all 11 staffers who’d been involved in the process, nine of whom were white. What an awkward meeting. I met them in this grand, lavish, colonial-style boardroom, and from across a formal table, I listened to the marketing chief declare that the words “white people” are “offensive” and appear “out of context” on the merch. (Isn’t all merch out of context?) Remember, this was an approved title. If a museum is going to approve an artwork’s title, either stand by it or don’t. The push-and-pull was infuriating and exhausting. Getting a clear position from the museum was like trying to play catch with a balloon.

One of the museum’s staff members, who was white, came to my defense in that boardroom. He exposed the museum’s hypocrisy by holding up its own branded tote bag that bore only the word “Asian” on it, and as I remember it he said, “I’m a white man walking around San Francisco with this bag that just says ‘Asian’ on it, without ‘museum,’ and it’s completely ‘out of context.’ Why is our bag okay but Chiraag’s is not?” The marketing chief’s response: “Well, that’s our brand, so it’s okay.”

And what to do with all those stacks of merch that they weren’t going to sell anymore? I joked that they should ship them to India—put some shirts on kids’ backs and create some interesting conversation. My other suggestion: Give the merch back to me. The museum eventually pulled all my bags and shirts from the store and sold them to me for a total of $1, to acknowledge the transaction.

The opening parties featured Indian classical music performed by white people, acro-yoga performed by white people, a chanting group mostly comprising white people, and a white couple from Marin teaching yoga for an hour. There was a sprinkle of Brown acts, but the headliner—wait for it—was a white rapper named MC Yogi, who spit about yoga and Indian culture over a beat dropped by DJ Drez, a white DJ with dreads. (Reminder: the largest institution of Asian art in the United States.)

Onstage behind the musicians was a massive projection of MC Yogi’s name, an Om symbol, and a crown—the very symbol of British oppression over India for hundreds of years. Here was a white artist mashing symbols and cultures—Indian and hip-hop—to root his identity in the fetishization of Brown and cool purely for his own benefit, disregarding communities of color.

Musicians perform at a 2014 gala celebrating the Asian Art Museum’s Yoga: The Art of Transformation.

Claudine Gossett for Drew Altizer Photography

To a certain kind of liberal-minded white person, perspectives like MC Yogi’s are commonly viewed as positive. He is “sharing” and “celebrating” cultures, not raiding them for his own benefit. In these contexts, positivity acts as a sort of Trojan horse; it’s how you smuggle white supremacy into the gates. Perspectives like mine, on the other hand, are widely seen as negative, divisive. The title of my upcoming show in Los Angeles plays on this concept: Why You So Negative?

The yoga show in 2013–2014 was scheduled to make one last stop after San Francisco, in Cleveland. I spoke with the Cleveland Art Museum to see if its curators wanted to include my installation. The lead curator said the idea was “hugely interesting” and “there is a lot of enthusiasm for your project here at CMA.” The curator flew to San Francisco and met me in person. Enthusiasm kept building. The conversation progressed far enough that we began talking costs, which didn’t seem like a sticking point. The curator even emailed me an internal floorplan of the show to finalize gallery placement.

After more than a month of fine-tuning our plans, the curator said there was one last “hurdle” to clear before approval: The Cleveland museum planned to invite the city’s commercial yoga studios to teach classes and had to make sure the studios felt comfortable in the same space as an installation titled #WhitePeopleDoingYoga. That’s when the plans fell apart. Out of nowhere, the curator—the uneasy messenger—emailed me to say the museum felt that my installation would be “ad hoc” (odd, given that we’d spent a month planning it). And, wait, what had happened to that last “hurdle”? It’s not surprising that local businesses could mute a museum’s platform; that’s what happens when you trade curatorial integrity for financial obligations. (Mother Jones couldn’t reach the curator for comment.)

The whole ordeal left me exhausted. My own community was a source of comfort, though. My friend Vijay Iyer, the jazz composer, MacArthur “genius” grant winner, and Harvard arts professor, gave me reassurance that I was not alone. In a talk he delivered in 2014 at Yale, he mentioned my installation in San Francisco, saying it was part of a “problematic exhibit,” and called out “Northern California culture’s imperial relationship to all things Indian.” Vijay was speaking as a South Asian American who’d spent plenty of time “navigating and resisting the exoticizing, incorporating tendencies of white American cultural omnivores”:

Because of the circles I traveled in as an artist, I noticed a similar tendency in the way that whites in the Bay Area dealt with jazz, hip-hop, and all things Black: not as a defiant assertion of Black identity and community, but as the fetishized trappings of cool—something white people could wear, collect, or otherwise incorporate into white subjectivity.

That was it: My experience with the Asian Art Museum was an exercise in watching white people work out their identity on the back of mine. The platform they seemed to give me, it turned out, wasn’t actually for me—it was for them, a way to fashion my Brownness into something they could wear. White supremacy works that way, for all “minorities”; it censors any critique contained in nonwhite expression and commodifies and tokenizes whatever’s left, forcing people like me into the posture of the model minority.

But I’m the negative one, right?

You can find more about Chiraag Bhakta’s work on PardonMyHindi.com. His solo show, Why You So Negative?, opens Friday and runs through October 27 at Human Resources in Los Angeles, at 410 Cottage Home Street, HumanResourcesLA.com. The show’s programming includes a performance by artist Nikhil Chopra, who recently performed and has work up at the Met and SFMOMA. A yoga class will also take place the following weekend.

Chiraag is advised by Dr. Roger Neesh.