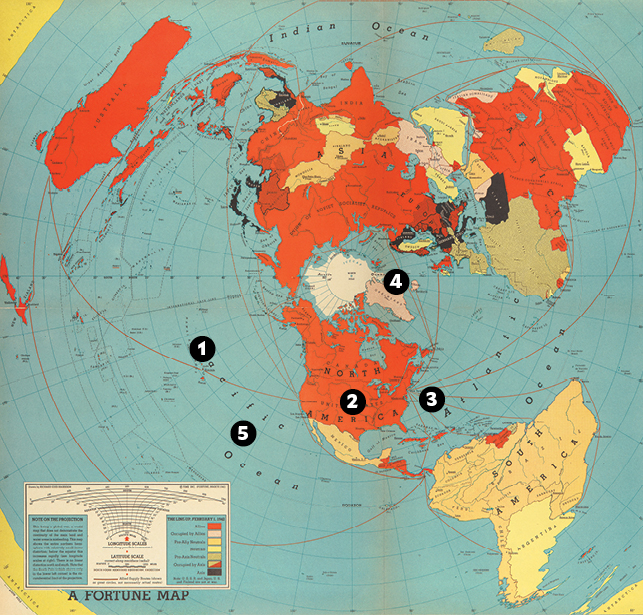

For the world to be made anew, it would have to be seen anew. Richard Edes Harrison’s influential pilot’s-eye-view map, first published in 1941, both reflected and facilitated a changing vision of the United States’ place in the international order. The map put the country in the middle of a portrait of global mutual obligation and threat—not a conqueror so much as the pivot around which the world would be organized. Look closely and you can begin to see the outlines of a different kind of empire.

1) Pearl Harbor was not just a military crisis for the United States. It was a cartographic one, too. Strategists decried Mercator projection maps, which made the country seem insulated from both fronts of World War II and encouraged aloofness. Harrison, the dean of wartime mapping, offered this projection instead. What you see here is a 1942 version. It shows Axis-riddled Eurasia and North America huddled around the North Pole. In the age of sail, the Arctic had been impassable, but in the air age it was the bridge to the fronts—and it appears here as the center of the world. Rather than separating the Old World from the New World, Harrison’s map highlights their connection. It was an enormous hit, reprinted and copied frequently. Joseph Goebbels waved it in reporters’ faces as proof of the United States’ world-conquering ambitions. The war had made the country a global presence—to use a word that came into vogue in the 1940s—and nothing showed it better than Harrison’s map.

2) The map, known as a polar azimuthal equidistant projection, is jarring to anyone used to Mercator. But the map’s challenging novelty was part of its allure at a time when the United States was reimagining its place in the world. There is one familiar locale, however: North America. Harrison shows it in its customary north-is-up orientation, with its shape easily recognizable. The US-centricity of this map would later become an issue when the United Nations, founded at the war’s end, adapted it for the organization’s logo. The UN decided to tilt the map 90 degrees clockwise so that the United States would not so obviously be the center of the world.

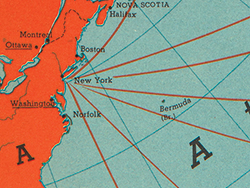

3) Thin lines representing “Allied Supply Routes” connect the ports of New York and San Francisco to war fronts as far as Suez, Egypt; and Chongqing, China. The United States served as quartermaster to the world, flooding its allies with supplies via a vast system of ports and air bases. This inaugurated a new model of global power—one based less on seizing large swaths of land than on controlling small areas. Today, the Pentagon claims about 800 bases in more than 70 foreign countries—a pointillist empire.

4) Greenland, usually a distended mass on the upper margin of Mercator maps, here appears the right size and central to the proceedings. The United States took control of Greenland during the war (which is why it is marked as “Allied-occupied”), long before President Donald Trump mused about buying the place. The US has maintained a military presence there ever since, and this map shows why: Greenland is the stepping stone to Western Europe and Russia. During the Cold War, the military ran an airborne alert program through Greenland, flying armed nuclear weapons over the territory so it could quickly strike the Soviet Union if ordered.

5) Concentric latitude circles—different from the parallel latitude lines of the Mercator projection—vividly emphasize the roundness of the planet. For wartime map readers, a round world meant one universally touched by the common conflict, with no room to sit things out—hence Harrison’s title, “One World, One War.” “If we win this war,” wrote the Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, “the image of the age which is now opening will be this image of a global earth, a completed sphere.” Champions of the azimuthal equidistant projection argued that the security of the United States was now a world matter, not just a regional one. With this map in hand, they won that argument. A new way of seeing the world was essential to the new ways of dominating it. Harrison would go on to consult for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

Adapted from How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)