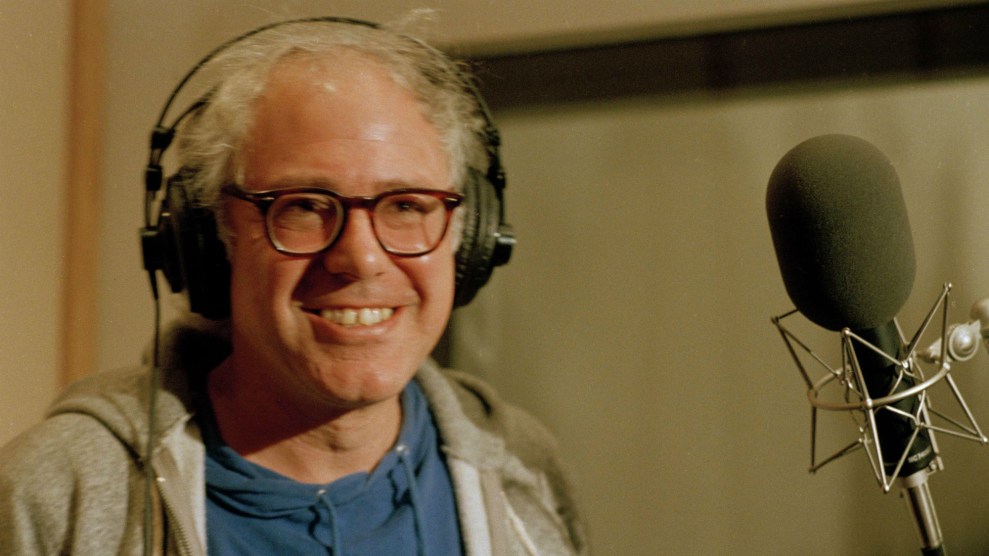

In 1987, Mayor Bernie Sanders pauses at a recording session.Toby Talbot/AP

On January 3, after U.S. military drones assassinated Iranian General Qassem Soleimani and Donald Trump began fumbling toward war with Iran, Sen. Bernie Sanders posted an anti-war video on Twitter. It shows the Democratic presidential candidate striding down a hallway, admonishing the camera. “I was right about Vietnam. I was right about Iraq. I will do everything in my power to prevent a war with Iran,” the caption reads. “I apologize to no one.”

A standard Bernie riff, and an urgent one. Nothing surprising there. What was weird was the music running beneath it: syncopation, bursts of double-time synth hi-hats, a touch of EDM. As one Twitter user wondered:

Why the fuck Bernie Sanders drop a trap beat mid video https://t.co/CEj0VGEwCH

— _riq (@mvnza) January 3, 2020

It turns out that Bernie loves a trap beat. Developed by hip-hop producers in Atlanta and across the South in the aughts, trap has risen to prominence and at times even melded into pop music’s genre-amorphous production palate. By 2017, it found Bernie. Flittering hi-hats, 808 drum sounds, and bouncing spectral synths began accompanying videos on textbook issues: the myth of trickle-down economics, Amazon not paying living wages, immigration reform. But the anti-war video was different. The unapologetic real talk about a manifestly grave issue, the rap braggadocio from a guy who once put out an album of lefty folk classics, the low-budget music video aesthetic—all of it led to the birth of a sort of meme. Trap Beat Bernie.

To discuss the beats, their thematic connections to Sanders’ core issues, and how his team thinks about its use of music, Mother Jones spoke to Ansel Herz and Katie Downey, respectively digital director and deputy digital director for Sanders’ press office.

Where do the beats come from? I presume you’re not making the beats in house for the videos.

Ansel Herz: It’s a paid database of licensed music that we’re accessing. It has a big range of producers, and there are lots of different kinds of music on there. We do often use trap beats, but we sometimes mix it up and use other kinds of music too.

Do you know the names of any of the beats or producers you have used?

AH: A producer that we’ve had we’ve relied on fairly heavily goes by Cushy. [His songs] tend to have pretty basic names: one of them is called “Bouncing.” One of them is called “Goodness.” There’s another producer who goes by Damma Beatz, and one of his tracks [that we’ve used] is called “Yes to That.”

Who chooses the beats for the videos?

Katie Downey: Whoever the producer is on that particular video gets to choose the vibe and the track that’s way down underneath it. I like to lay down kind of an aggressive beat to keep it moving.

Trap is often irreverent, cartoonish, and fun, but has also frequently addressed the realities of poverty and the war on drugs—with beats to match. Do you see a thematic connection the subjects Bernie is discussing in these videos? For example, when his anti-Iran War video came out last May, I saw people tweeting things like “why is this so hard?” as if he were spitting bars over the beat.

KD: I chose that track because the senator was very passionate about what he was saying. He really wanted to convey the importance of his message surrounding the current foreign policy of our country and the administration that we’re currently under. And he really wanted to express his deep concern around some of the decisions that are being made surrounding foreign policy.

Keeping in mind how passionate he is about this—that’s really why I chose that track. Foreign policy is not a dry issue; it’s very important to many people for good reason. Just laying that track underneath was kind of like the cherry on top that just. It propelled his momentum of the words he was saying and, like you said, it kind of sounds like he’s spitting bars. His rhythm and the trap beat are meant to go hand in hand, and it’s meant to be a unified sound for the viewer, and also to resonate the message.

It seems like that message has, unfortunately, become hyper relevant again lately.

AH: The video of Bernie walking through the hallway talking about his opposition to war—that went out in May when the Trump administration was doing a lot of saber-rattling around Iran. When this attack took place, most recently, the message really hasn’t changed very much in terms of the senator’s complete opposition to starting a new war in Iran.

And so we made the decision to put [the video] out again, and it had attracted about 2 million views the first time we posted it. And then today now, it’s added another 4.5 million views. And if you look at the statistics on that particular tweet, it outperformed virtually every tweet from the president himself, the @realDonaldTrump account, that had been trying to make the case for war, or for attacking Iran.

How does your office use and think about music beyond trap beats and these policy videos?

AH: In general, looking for things that are going to help energize people and resonate with the tone of whatever given video we’re putting out. We’re working on one now that has to do with fires in the Amazon rainforest and global warming. For that video, I don’t think we’re going to use a trap beat. It’s a little bit more slow and a little bit more somber because we just decided that that kind of fits the mood of the video. It’s talking about how critical the rain forest is to the future of the planet and thematically it just made it better.

Back in 2016, there was a perhaps unfounded but persistent narrative that the Sanders campaign with not doing enough outreach to communities of color. Does the Senator’s press office factor those past perceived concerns into the decision-making about using trap beats—music that came out of the black community?

AH: We’re pulling from the music that’s available to us, and our focus is on producing videos that we know are going to resonate with both communities of color and other communities around the country. And, like I said, we adjust the musical choice based on the theme, the mood of the video, and sometimes the subject matter as well.