“It begins with the subject,” Dawoud Bey has said of his photography. “A deep interest in wanting to describe the Black subject in a way that’s as complex as the experiences of anyone else. It’s meant to kind of reshape the world one person at a time.”

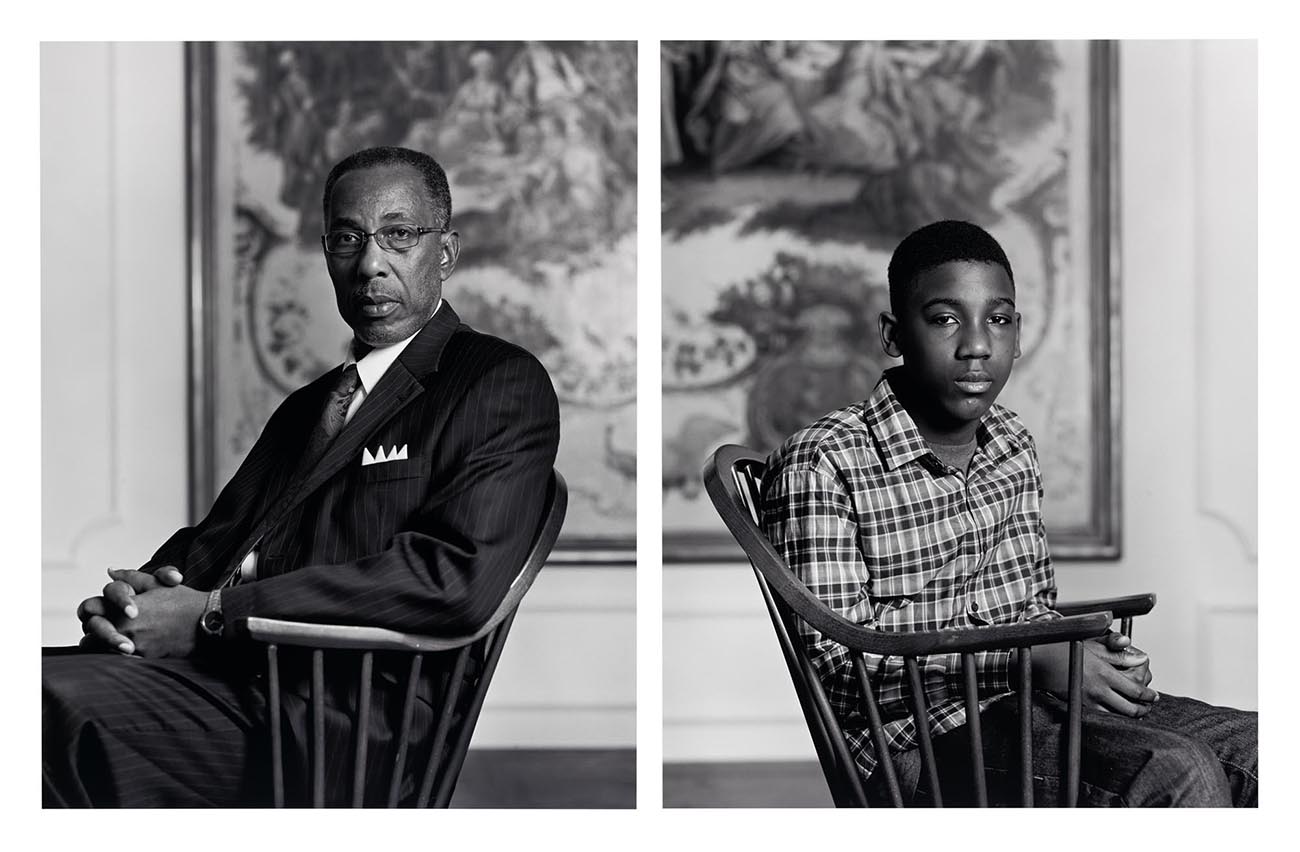

It is an audacious mission, but Bey’s work—now the subject of a career retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art—lives up to this ambition. The diptychs above are part of The Birmingham Project, which wasn’t so much a commemoration of the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 as a kind of seance. Each pairing in the series features two Birminghamians photographed in 2013: One is a child the same age as the boys and girls who died in the bombing; the other is an adult as old as the victims would have been had they lived. With these portraits, Bey wanted to bring the bombing out of the attics of the mind, to confront viewers not just with the youth of the murdered children but with the hollow of the lives that went unlived. This was history brought to life.

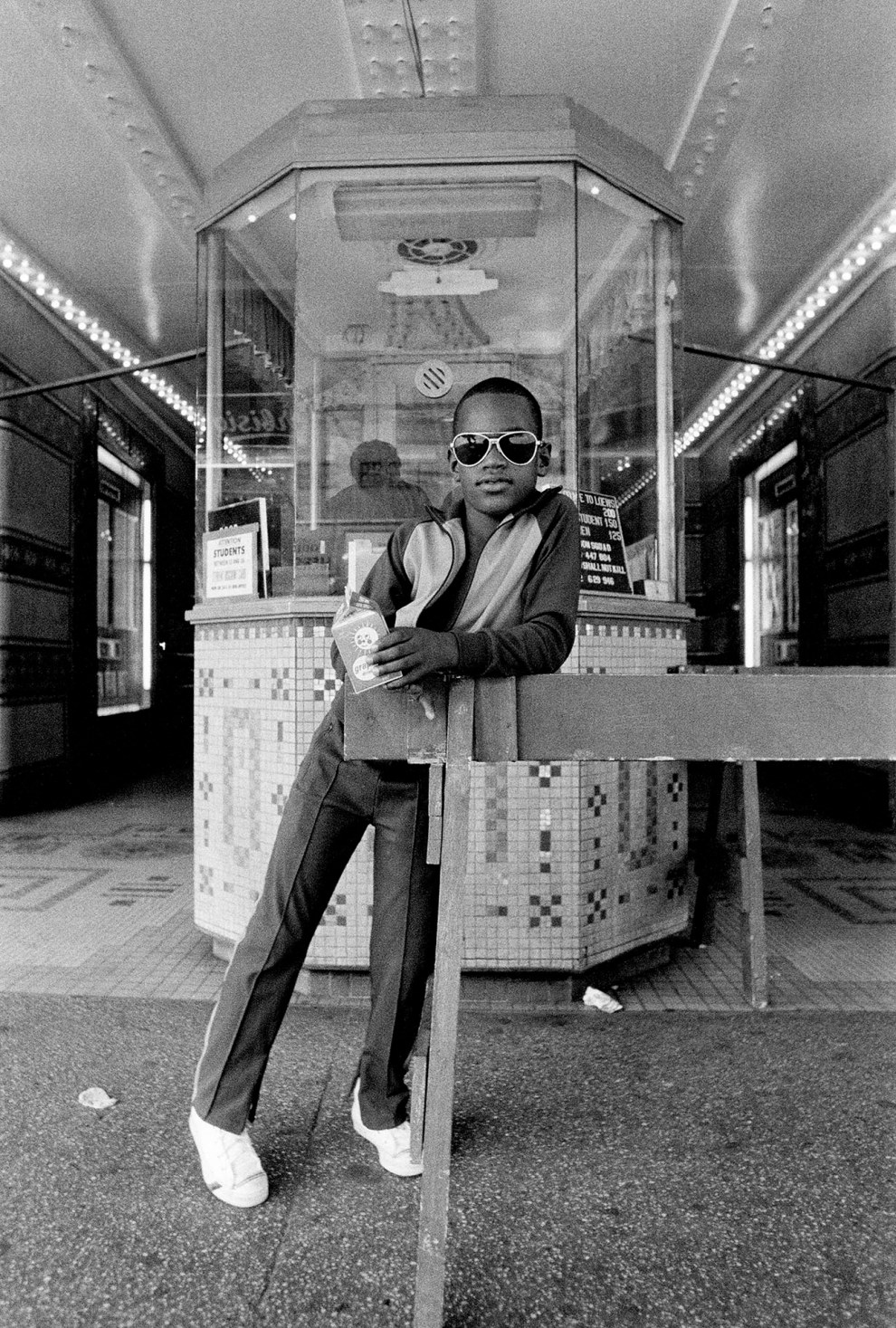

Bey began his career as a street photographer in the 1970s, focusing on African American communities and Harlem in particular. Unlike the snatch-and-grab style of noted street photographer Garry Winogrand, Bey made considered portraits of people he met. This documentation of everyday life in a largely overlooked (if not harshly stereotyped) part of New York City was part of Bey’s mission to refocus how African American communities were photographed, and thus, seen.

“Three Women at a Parade, Harlem, NY,” from the Series Harlem U.S.A., 1978.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

“A Boy in Front of Lowe’s 125th Street Movie Theater, Harlem, NY,” from the series Harlem U.S.A., 1976.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

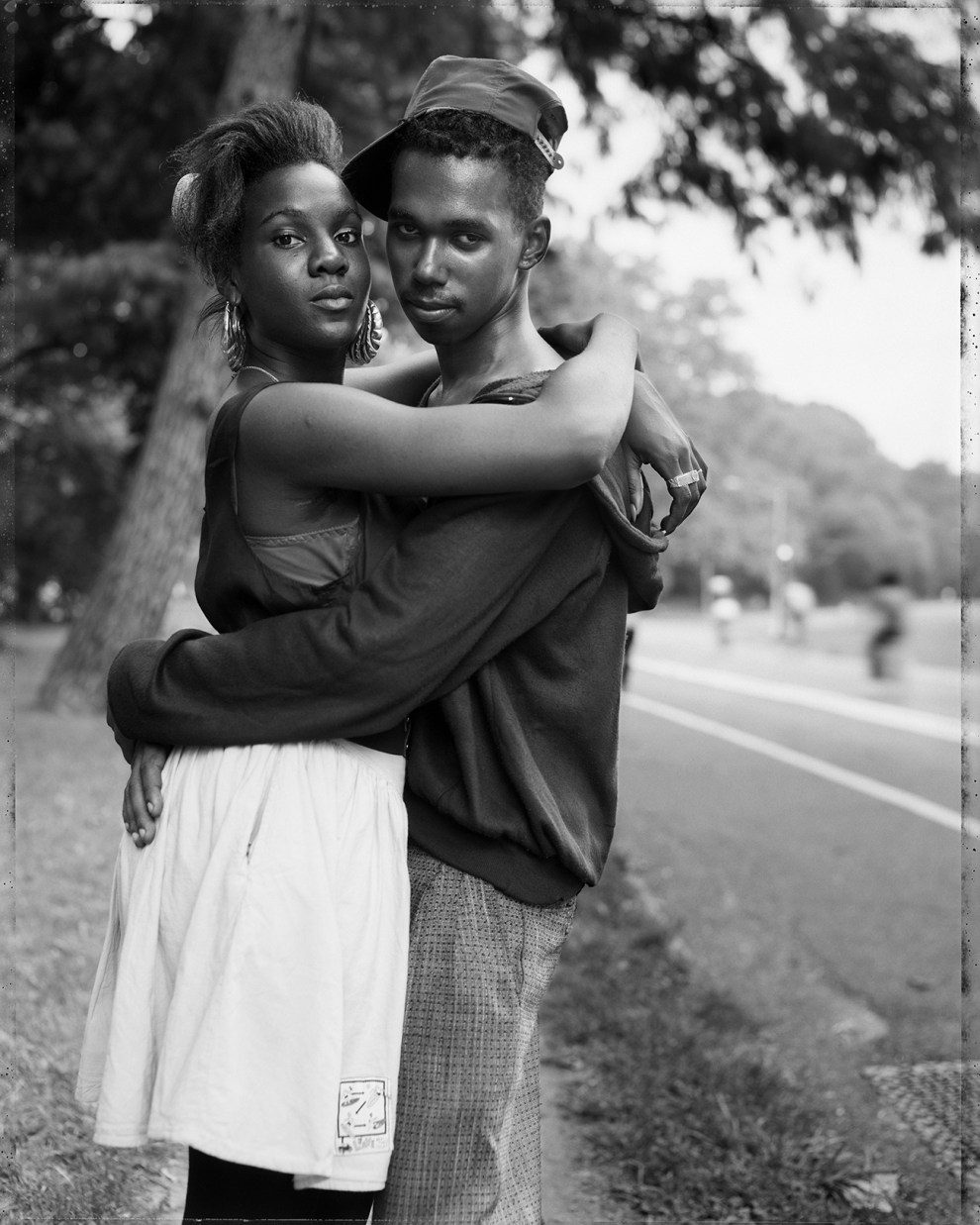

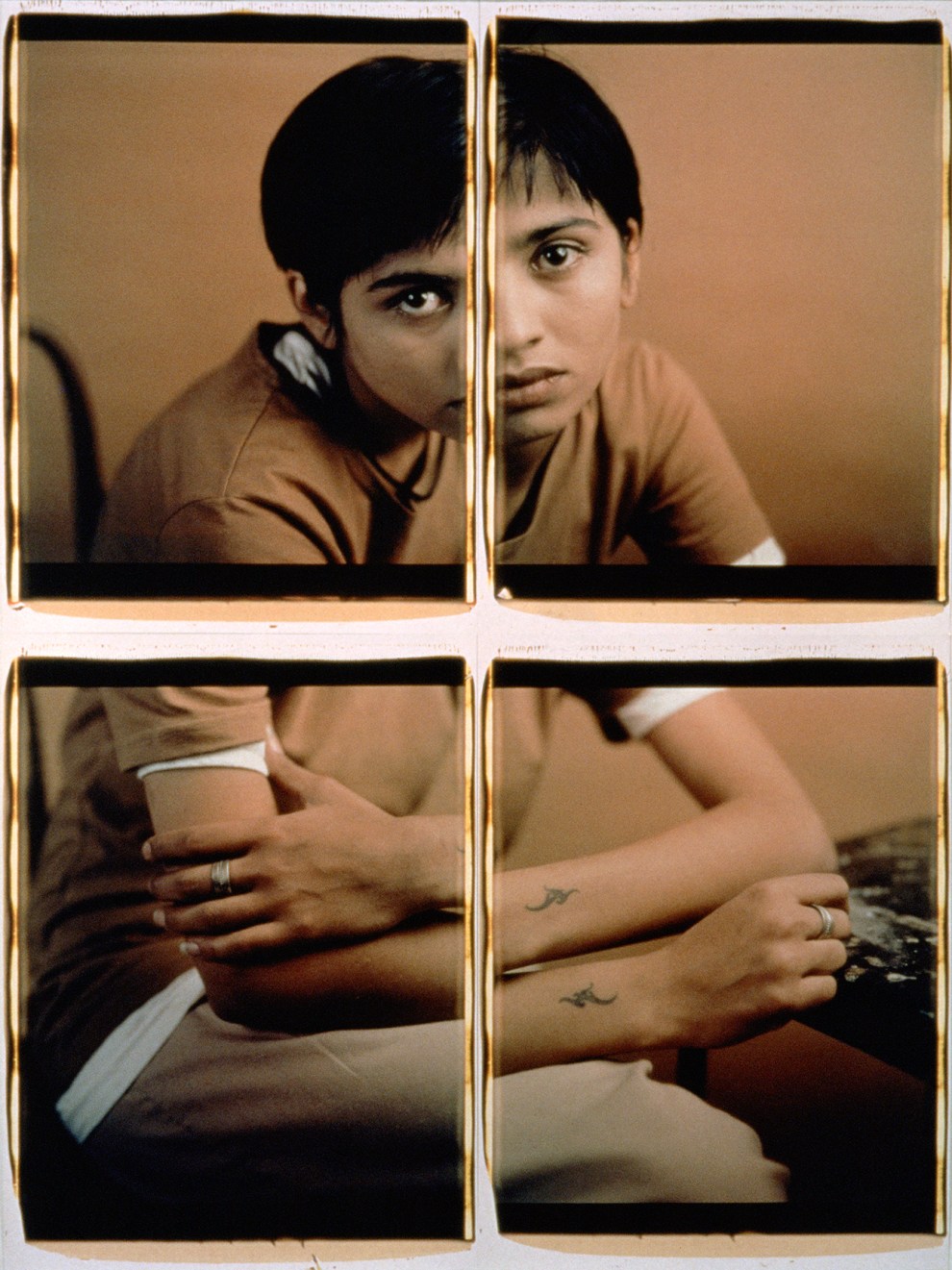

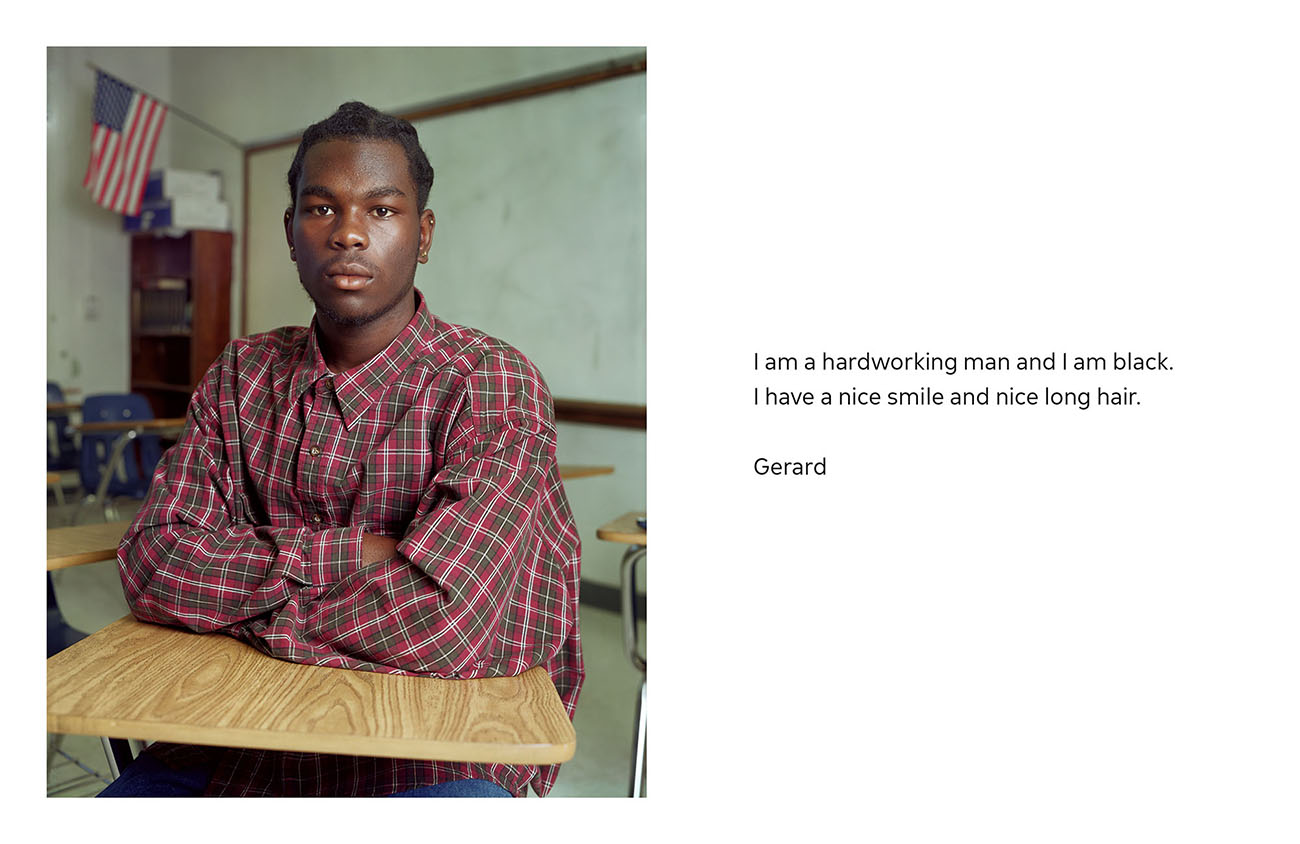

In the late 1980s through the 90s, Bey continued using portraiture to explore identity and community. Those efforts culminated in three outstanding projects: his Black-and-White Type 55 Polaroid Street Portraits series, a collection of large color Polaroid collage portraits, and a sequence of collaborative portraits of early 2000s high school students across the country.

“A Couple in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY,” 1990.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

“A Boy Eating a Foxy Pop, Brooklyn, NY,” 1988.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

“Alva, New York, NY,” 1992.

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy

“Amishi, Chicago, IL,” 1993.

Los Angele County Museum of Art, Ralph M Parsons Fund

“Gerard, Edgewater High School, Orlando, FL,” from the series Class Pictures, 2003.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

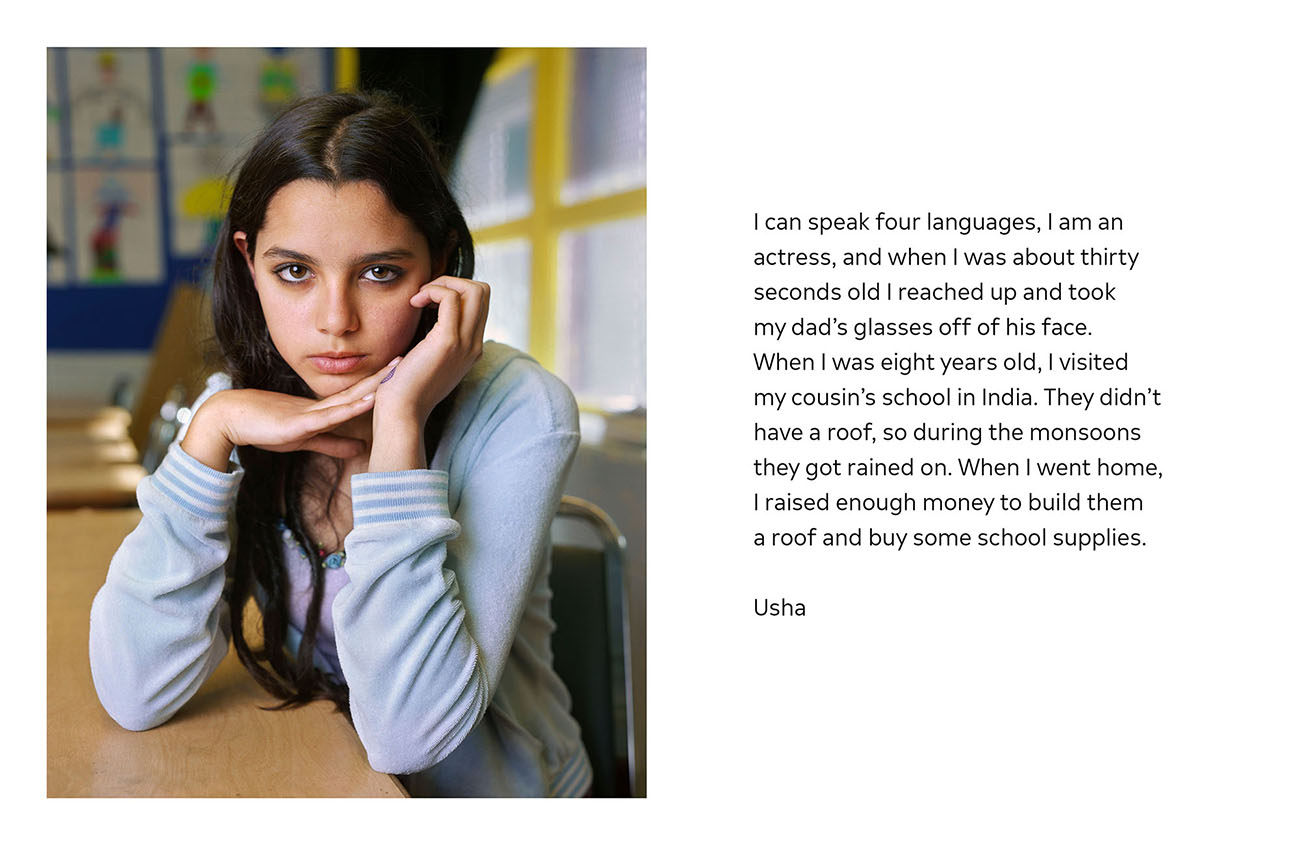

“Usha, Gateway High School, San Francisco, CA,” from the series Class Pictures, 2006.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

Then, almost forty years after his original project, Bey returned to Harlem. He photographed the same neighborhood. This time using gorgeous, large format color images that noted drastic changes. Harlem Redux is mostly landscapes and streetscape, made between 2014–2017, in which gentrification and displacement lurk. The city streets and buildings are the subjects. It is more subtle, yet more critical than most of Bey’s other work.

“Girls, Ornaments, and Vacant Lot, Harlem, NY,” from the series Harlem Redux, 2016.

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery

In more recent years, Bey shifted his work to a reimaging of history. Night Coming Tenderly shows large black and white landscape images—printed dark, as if shot at night—to imagine what fugitive slaves on the underground railroad saw on their journey north. It was mostly photographed in Ohio, near former safe houses.

“Mary Park and Caela Cowan, Birmingham, AL,” from the series The Birmingham Project, 2012

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

“Don Sledge and Moses Austin, Birmingham, AL,” from the series The Birmingham Project, 2012

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

“Untitled #20 (Farmhouse and Picket Fence I),” from the series Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017

San Francisco Museum of Art

“Untitled #25 (Lake Erie and Sky),” from the series Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017

San Francisco Museum of Art

The retrospective, An American Project, forces the viewer to consider (or reconsider) what constitutes a body of “American” photography. Nearly every collection representing American photography—going back to Walker Evans’ landmark 1938 project American Photographs—has focused on, featured and been made by white men. This retrospect, co-curated with the Whitney, shows Bey’s long experience attempting to represent a different story.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project is on display at the San Francisco Museum of Art from February 15 – May 25, 2020.