David Attie/Getty

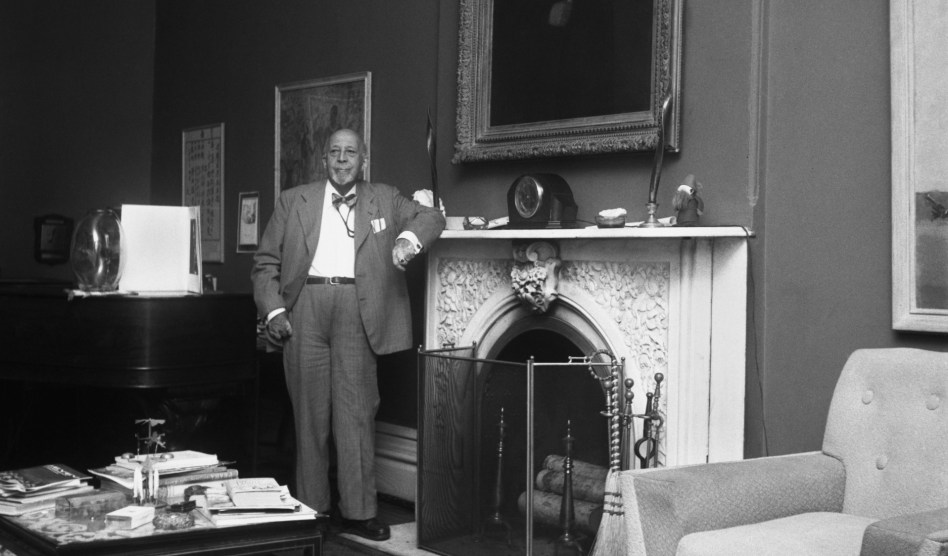

Around the time Wesley Lowery described in the New York Times a “reckoning over objectivity” in journalism, I was reading an introduction to W.E.B. Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction in America by Dr. David Levering Lewis.

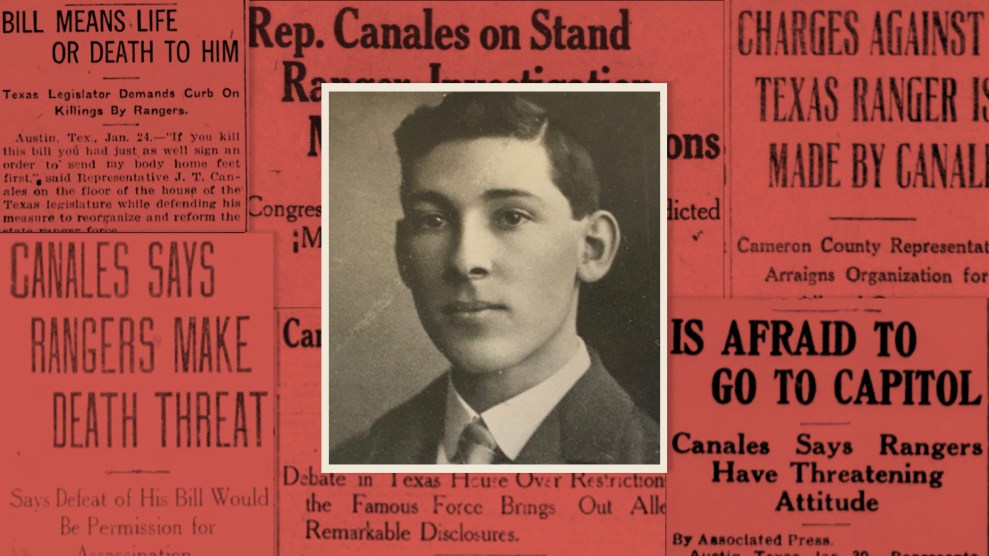

Lewis mentions an incident I have not heard much discussed: the censorship of Du Bois by a white editor at the Encyclopedia Britannica named Franklin Henry Hooper. This happened in 1929. A century later, the incident and its implications chime with Lowery’s observations about editors seeing the work of Black people as hopelessly biased and “the views and inclinations of whiteness” as the “objective neutral.” Then, as now, the forms of liberal rationalism were put to reactionary use. The encyclopedia, Lewis writes, had demonstrated “how color-coded cognitive dissonance impelled most educated white people, in the name of ‘objective’ history and social science, to discount the beliefs of most educated colored people as propaganda or fiction.”

The affair played out over a series of letters, which have been digitized by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. You can find them all here. They contain other echoes of our present media culture—the debate about capitalizing the “n” in “Negro”; Du Bois rallying fellow Black writers to the cause, imploring them in a letter to “stand as a unit”; Hooper reminding Du Bois that facts don’t care about his feelings; Du Bois getting stiffed on his payment. The people who are in charge today are the same sort of people who were in charge 90 years ago. They reach for the same tools to beat back any challenge to the sustaining fictions of the social order, whether they’re defending the prerogatives of the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1929 or the New York Times op-ed page in 2020.

Here is the basic situation: In the mid 1920s, Du Bois was recruited to write for the encyclopedia. He was already a giant of his time, having published The Souls of Black Folk and Darkwater, and having co-founded the NAACP. His project was in many ways a long, twilight battle against the idea of whiteness as neutral. His academic work in the realms of history and economics centered Black lives and Black agency. The Souls of Black Folk discussed how Black self-conception was filtered through a white world, creating a “double-consciousness” or “twoness.” Writing for Britannica, that bastion of the objective neutral, Du Bois had a unique chance to reshape consensus narratives from within.

He took it on with zeal. First, he was asked to write an entry on Black literature for the encyclopedia. A few years later, he was tapped for a larger entry on “The Negro in the United States” generally. Du Bois used the assignment as an opportunity to recruit other Black scholars, among them the famous philosopher Alain Locke. “In light of the distortions and even grotesqueries written about people of color in standard reference works of the period, access to the Encyclopedia Britannica was greeted with an almost pitiable hopefulness—so much was theirs in mainstream America to so little allow,” writes Lewis in the second volume of his two-part biography of Du Bois (both parts of which won separate Pulitzer prizes).

But as Lewis explains, a “corporate upheaval” at the encyclopedia left Du Bois working with a new editor: Franklin Henry Hooper. Hooper, in the letters, fully inhabits the role of the bad white editor. He is brusque, supercilious, late, and wrong. When he wants to change something in the proof, it is explained as correcting a mistake. (It cannot just be an editorial decision.) Letters are passive-aggressive and condescending. Each is signed: “FRANKLIN H. HOOPER. AMERICAN EDITOR.”

In May of 1928, Du Bois turns in a draft of a general entry on the “American Negro” to Hooper. It is long, he admits—above the 5,000-word mark, nearing 9,000, even—but he’s confident he can cut it down if Hooper could tell him “what ground has been covered” on the subject by other encyclopedia contributors.

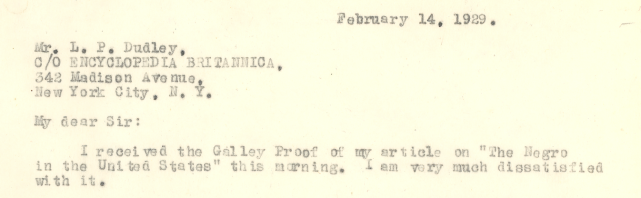

Eight months later, Hooper’s editorial assistant, L.P. Dudley, sends back an edited manuscript. Hooper has slashed it. Du Bois responds on the day he receives it. “I am very much dissatisfied,” he says.

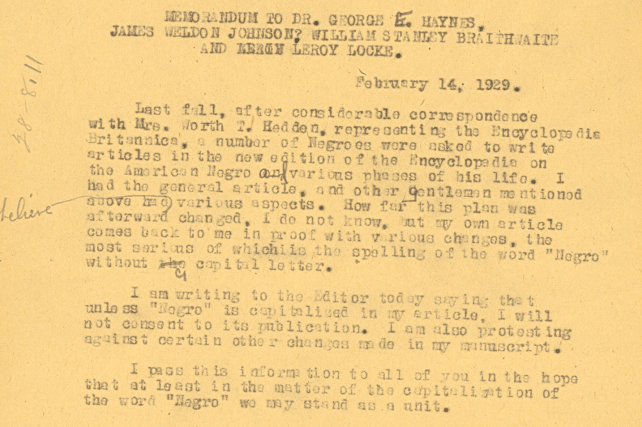

First, Du Bois notes it would be a “personal insult” not to capitalize the word “Negro,” a complaint that resonates with today’s debate over capitalizing the “b” in “Black.” At least some of Du Bois’ aggravation is surely due to the fact that Hooper already knows his feelings on the matter. In 1926, when Du Bois first wrote for the encyclopedia about African American literature, he’d exchanged letters with Hooper about capitalization, to which Hooper assented despite a general policy of capitalizing “as few words as possible.”

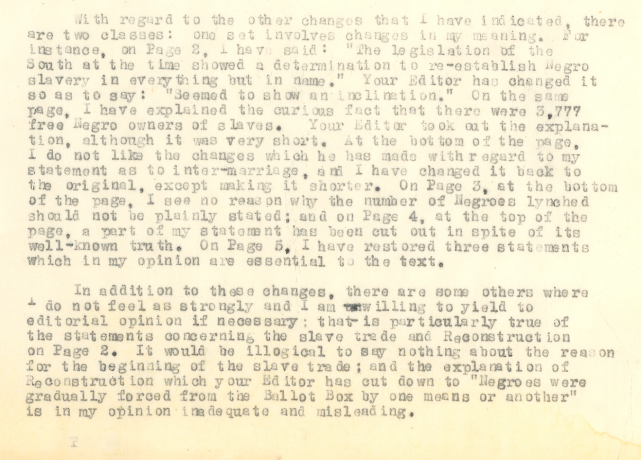

Du Bois then dives into the factual changes. They are myriad. Du Bois had written that Southern legislation “showed a determination to re-establish Negro slavery in everything but name.” Hooper has changed it to “seemed to show an inclination” to re-establish slavery. Du Bois had provided the precise number of lynchings. Hooper has made it vague. (“I see no reason why the number of Negroes lynched should not be plainly stated,” Du Bois says.) Du Bois had written, “Negroes were kept from voting at first by force and intimidation, then by fraud and finally by a series of laws which purported to disfranchise the illiterate, the propertyless, and those who did not pay their poll tax.” Hooper has soft-pedaled the description, writing, “Negroes were gradually forced from the Ballot Box by one means or another.”

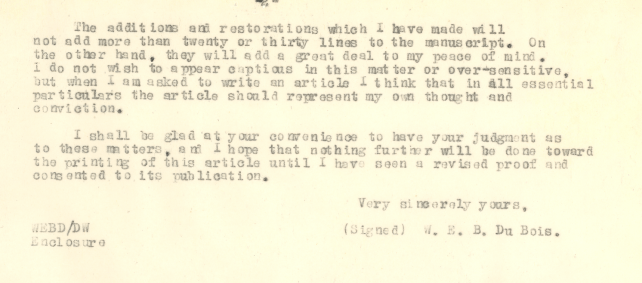

Hoping not to appear “captious or over-sensitive,” Du Bois explains in his response that the article “should represent my own thought and conviction” and not Hooper’s. These edits, he says, are not his beliefs.

That same day, Du Bois writes a letter warning the other Black writers he’d recruited for Britannica. Du Bois hopes to push back together. In particular, he wants to “stand as a unit” on “the matter of the capitalization of the word ‘Negro.'”

We know that Alain Locke agreed, as well as W.A. Robinson, who had been asked to write an article on the development of education for African Americans. In fact, Robinson was having his own run-ins with Britannica‘s editorial process at the time. He wound up sending his own letter to editors, saying that multiple changes they made to appease Southern readers were untrue.

Du Bois commiserates and strategizes in a letter to Robinson, also dated February 14 (though he notes that “the changes in mine are much more serious”).

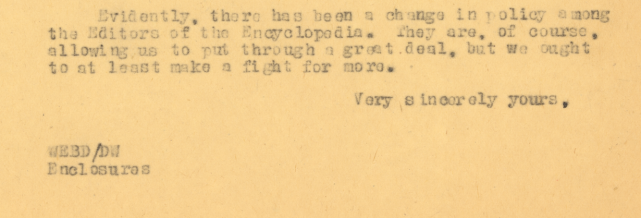

“Evidently, there has been a change in policy among the Editors of the Encyclopedia,” Du Bois writes. After conceding that the editors “are allowing us to put through a great deal,” he says “we ought to at least make a fight for more”—a demonstration of the way even the soft sort of inclusion favored by America’s liberal institutions can bring about real agitation for change.

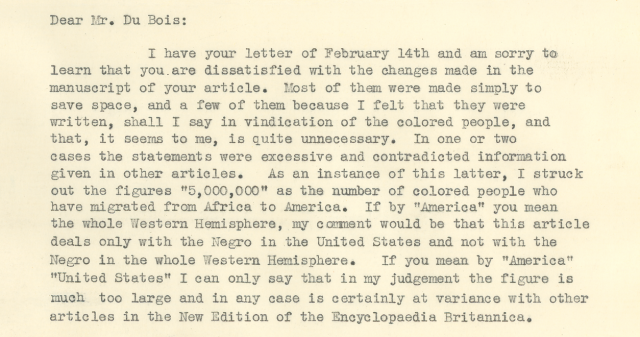

A few days later, Hooper writes back to Du Bois to explain his edits to the manuscript. He says that he made the changes because certain things were written “shall I say in vindication of the colored people”—he found that “quite unnecessary.” He adds that, in fact, some of the information “contradicted information in other articles” of the volume.

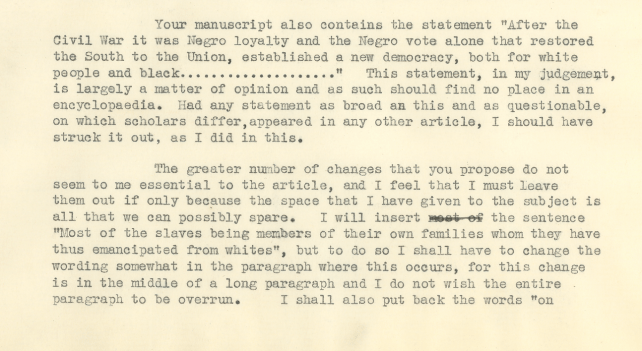

Hooper points out that Du Bois’ claim that Black Americans helped save democracy after the Civil War is “a matter of opinion and as such should find no place in an encyclopedia.” The editor concedes a few points—and half-heartedly agrees to capitalize “Negro,” as if the same conversation had not already happened—but otherwise brushes off Du Bois, saying his changes are about “space” while Du Bois’ proposed changes are inessential. Hooper says he must rush the article to press, even threatening to print the thing if “I do not hear from you by return mail.”

Du Bois is not satisfied. He sends another letter to Hooper to explain the changes he feels must be made before publication. At the end, he also responds to Hooper’s condescension about the necessity of the changes: “You say that these other changes ‘do not seem to me to be necessary’: but the point is that I am the author of the article and to me some change does seem necessary.”

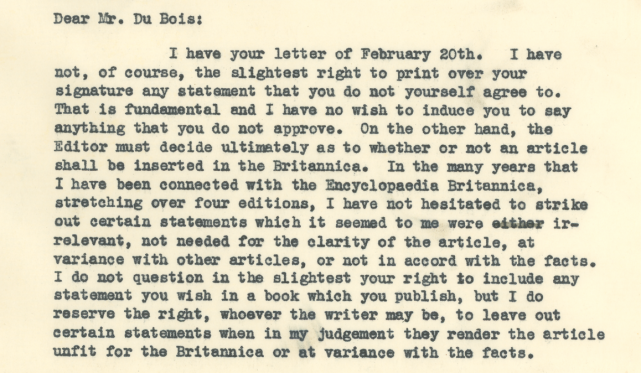

Does this rebuke stop Hooper or give him pause? Of course not. Striking a pose of cool-headed rationalism, he responds with a florid version of what would now be rendered as “facts not feelings.”

Hooper says he has made his changes and will publish the article with them. But he does not send the new version along.

Du Bois asks to see the actual article and will not allow it to be published until he does.

Du Bois has at this point reached out to a friend, Joel Spingarn, a white writer and fellow leader in the NAACP, for counsel on his “interesting experience” with Hooper, attaching both his correspondence and that of the other Britannica writers. Spingarn points out that the encyclopedia isn’t looking for the “fundamental truth” so much as a clear picture of “accepted” wisdom, and that Britannica is “more insular and one-sided than most works of the kind.”

Du Bois has also sent a letter to his original editor, Worth Hedden, about the “queer experiences” of the Black writers he’d recruited. The former editor explains that broad editorial changes at Britannica had led to his ousting, and, moreover, that he is not surprised Du Bois’ recruits were running into trouble.

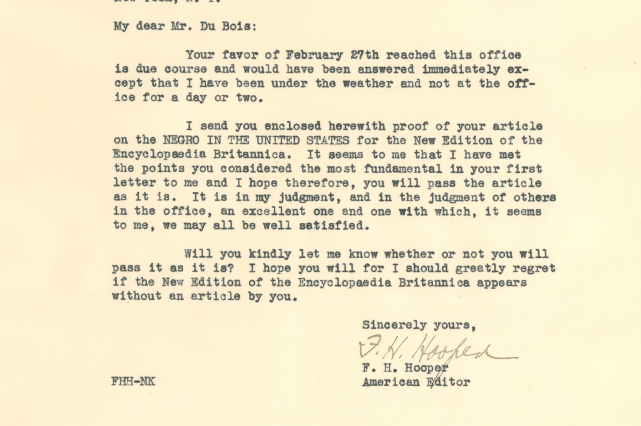

By the time Hooper finally sends the manuscript along—and tries to finish off the interaction to get final approval—Du Bois has formulated a plan.

Taking a suggestion from Spingarn, Du Bois insists on one last change.

We know from subsequent correspondence with Spingarn that Du Bois had wanted to insert this paragraph:

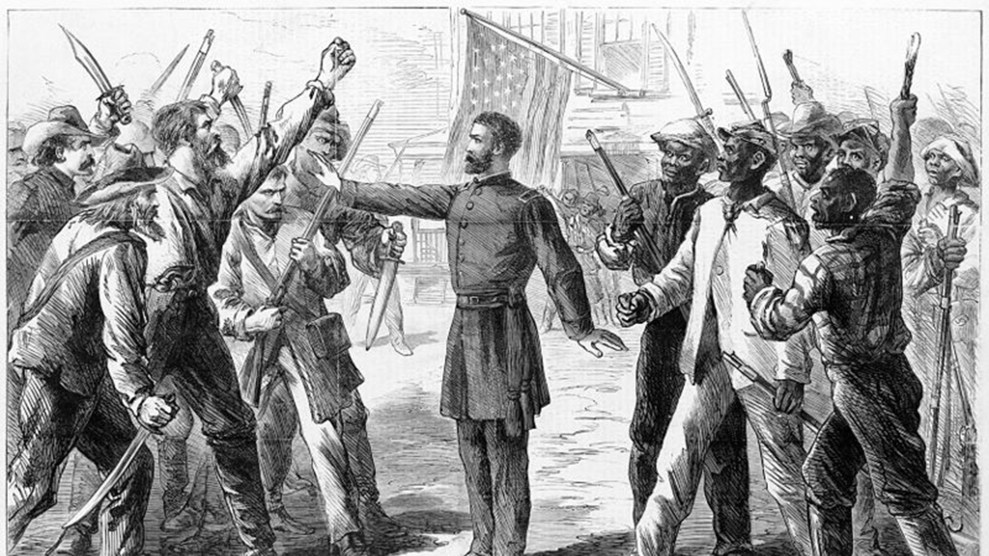

White historians have ascribed the faults and failures of Reconstruction to Negro ignorance and corruption. But the Negro insists that it was Negro loyalty and the Negro vote alone that restored the South to the Union; established the new Democracy, both for white and black, and instituted the public schools.

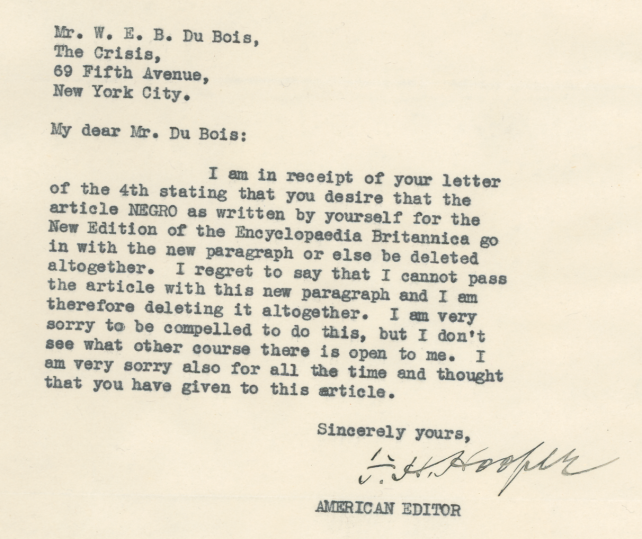

Hooper refuses. He kills the article, saying that he “cannot pass the article with this new paragraph and I am therefore deleting it altogether.”

Let us take a moment with this idea, so objectionable that Hooper kills the entire article. The claim that Black Americans saved democracy would become the bedrock of Black Reconstruction in America, considered Du Bois’ masterwork. (In 1933, Du Bois would even send his correspondence with Britannica to the publisher of Black Reconstruction—the rejection of the article for Britannica is marked as “the genesis” of the book, explains a note written by an archivist.)

The book is foundational on two fronts. Black Reconstruction posited post–Civil War lawmaking as a radical, Black-led movement to create a new democracy. It would lead to Eric Foner’s famous characterization of the time period as a “second founding.” Black Reconstruction also created a methodological breakthrough. This was a story centered on Black life, Black agency. It upended the prevailing ideas about who were the actors of history and who were the acted-upon. Even in miniature form, in his encyclopedia entry, Du Bois was challenging the very notion of an objective neutral over which the Britannica was created to stand sentry. The question his essay posed implicitly could be asked today of many newspaper editors or for that matter any number of adherents of the new rationalism: What “facts,” whose “truth,” are you really defending?

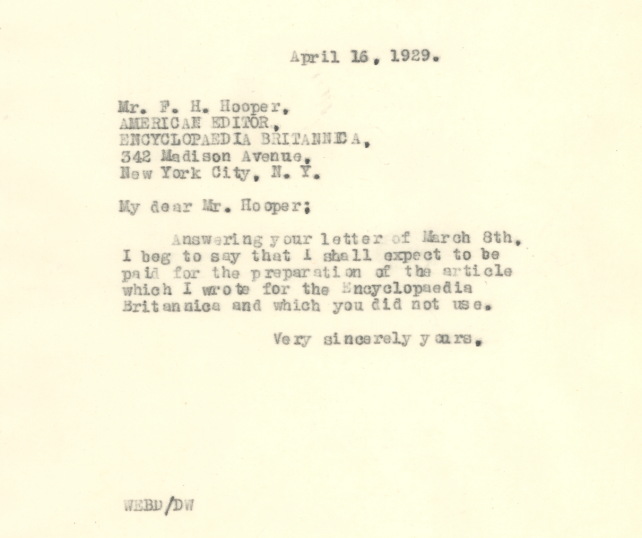

There is one last indignity to be visited on Du Bois. The encyclopedia won’t pay him for his work.

A couple months later:

Du Bois got his money in the end: $83.33 (nearly $1,300 today—a decent kill fee). David Levering Lewis says a white sociologist named Edwin Embree wound up writing the encyclopedia’s entry on Black people in the United States. And Hooper? A few years, he would be promoted to editor-in-chief of Britannica.

You can still read what Du Bois attempted to enter into the historical record, though; multiple drafts exist in Amherst’s collections. There is something affecting about reading it now, knowing what he’d gone through with Britannica. He ends with an admission that it is “difficult to express definitely just what social ostracism of American Negroes has meant in the past and just what it means now.” He says the “manifestations are subtle and its changes almost imperceptibly gradual.” For many years Black leaders felt uncomfortable even admitting they desired equality. Yet now, he writes, “under no circumstance, except by compulsion, will they accept a status of social inferiority.”