Herve Merliac/AP

Recently, when discussing the Mother Jones Daily with my boss and newsletter co-writer Ben Dreyfuss, he gave me free rein to write about pretty much anything. “If you want,” he said, “it can be about your favorite TV show.”

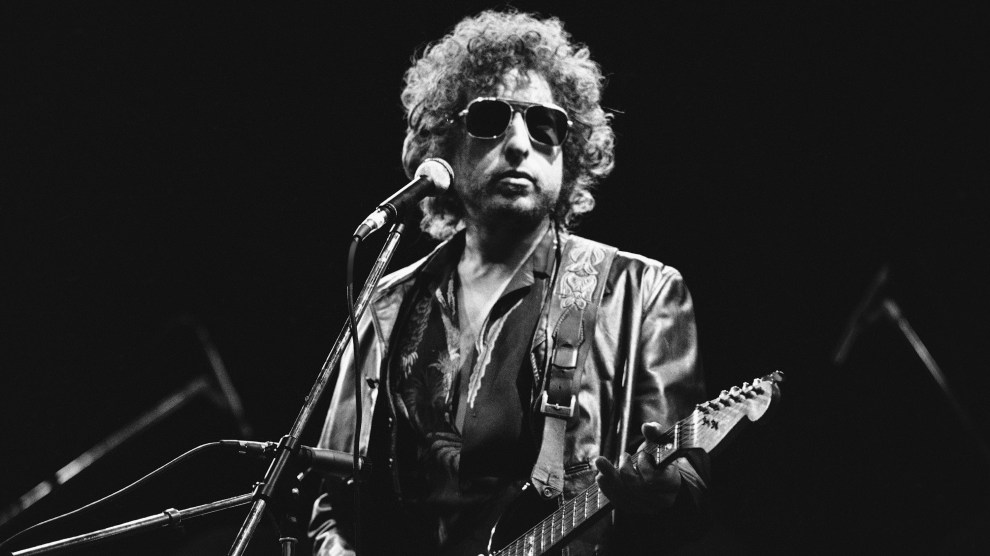

So, since it’s a Friday and I’m feeling whimsical, I’m going to write not about my favorite TV show, but about a musician I’m known to have a soft spot for: Bob Dylan. Bear with me here.

When I first got into Dylan a couple years ago, the disintegration of his relationship with his first wife, Sara, struck me as the most tragic thing in the world. I felt privileged to be able to chart the course of their relationship by listening to his albums back to back, rather than having to wait months or years between releases, as I would have if I were around in the ’60s and ’70s. In 1966, on Blonde on Blonde, Sara was the “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” with the “saintlike face” and “ghostlike soul.” In a decade, their relationship had gone to shit: On “Sara,” the final track of Desire, released in 1976, Dylan sings bitterly of “staying up for days in the Chelsea Hotel / writing ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ for you.”

But Blood on the Tracks is the breakup album everyone talks about, the one Jakob Dylan has called “my parents talking,” the devastating story of a man whose wife leaves him unexpectedly one night, and his only recourse is to wail about it for 51 minutes. But I realized, upon listening to the album recently, that I had been so blinded by Dylan’s brilliance that I had totally overlooked Sara’s side of the story: The man was probably absolutely insufferable to live with.

Dylan cheated on Sara. He drank heavily. His moods were famously mercurial. He allegedly (in 1977, two years after BOTT was released) brought one of his girlfriends home one morning, and when Sara snapped at the sight of a strange woman eating with her children at the breakfast table, he hit her in the jaw—so says Uncut magazine.

When you listen to the album closely, you start to notice small admissions of Dylan’s own guilt: on “Idiot Wind,” “You tamed the lion in my cage / But it just wasn’t enough to change my heart”; on “You’re a Big Girl Now,” “I can change, I swear.” He knew that losing her was his own damn fault. And he tricked suckers like me into thinking he was the victim all along.

I don’t value Blood on the Tracks any less because Dylan wasn’t the loyal husband I had naively assumed him to be. But I do think it’s a valuable lesson in questioning your assumptions and thinking critically of your idols, be they political, musical, whatever.

This post was brought to you by the Mother Jones Daily newsletter, which hits inboxes every weekday and is written by Ben Dreyfuss and Abigail Weinberg, and regularly features guest contributions by our much smarter colleagues. Sign up for it here.