Act I

Rape

He has lured her into his apartment, smeared her with cocaine, drenched her in opinions about Consider the Lobster as he inches closer to her on the futon. She is bleary-eyed, listless, her consonants soft at the edges. “I feel such a connection to you,” Neil assures her, before prying her bare legs apart with his hand. “I needa go home,” she says. “Noo, don’t go, stay,” he whispers, marking her neck with kisses. “Oh my god, you are so, so pretty.” “I need to go home,” she repeats, but instead his hands disappear under her skirt.

Then her eyes snap open. “Hey Neil,” she says, no longer drunk, her voice suddenly self-assured and lucid, her hand shooting out to grab his face: “I said I need to go home.”

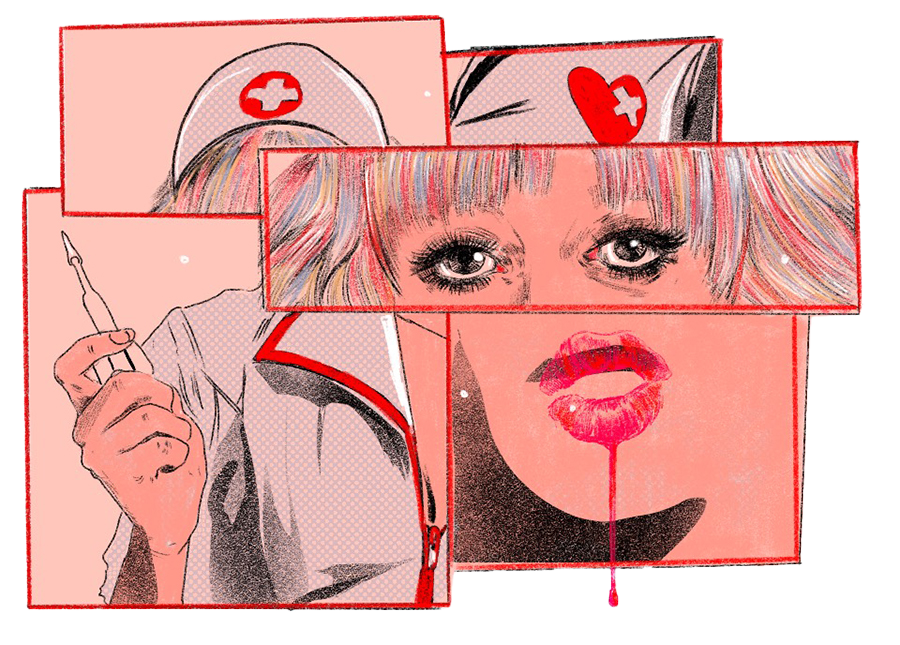

If you’ve seen Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, you anticipated this sudden reversal. In several of the film’s opening scenes, ultra-feminine Cassie, played by Carey Mulligan, tricks a random man into thinking she’s inebriated, follows along as he tries to hook up with her without her consent, and then 180s on him, abruptly casting off her intoxication to shame her would-be rapist in the act.

Her motivation trickles out as the film progresses: Cassie’s best friend, Nina, was raped while in medical school, causing her to drop out and then presumably to kill herself. After watching the man who assaulted Nina go unpunished, friends become complacent, and the school ignore the incident, Cassie steps into a new role: that of voracious avenger. Her ploys continue to escalate and become more destructive, riding the steady winds of her rage.

In Promising Young Woman, justice takes the form of the rape-revenge narrative, in which a character experiences or witnesses an act of sexual violence and then extracts vengeance on the perpetrator. The rape-revenge narrative has had a resurgence in recent years, as a sort of wish fulfillment for the #MeToo era. But the plot device is nothing new; it spawned a whole subgenre of exploitation films back in the 1970s, including the gory thriller I Spit on Your Grave, and continued to turn up in hundreds of movies over the decades.

Rape-revenge films aren’t feminist, per se, but rather they represent the “way in which Hollywood can be seen to be making sense of feminism,” argues scholar Jacinda Read in her 2000 book, The New Avengers: Feminism, Femininity, and the Rape-Revenge Cycle. The films resist broad characterization, notes Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, the author of Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study. Taken as a whole, she wrote in an email, the films “articulate just how confused and hypocritical our broader attitudes to gendered violence and sexism in general are.”

Diverse as these stories may be, they tend to present a similar sequence of events, Read points out: rape, transformation of the victim, and then revenge. In several post-#MeToo iterations, the avenger targets not only a single perpetrator of rape, but rape culture more broadly. Such is the case in Promising Young Woman. Cassie unleashes on lascivious men, witnesses, lawyers, and school administrators—an entire network that legitimized her friend’s rape and others like it.

It’s also the case in Lisa Taddeo’s new novel, Animal. Taddeo made waves with her 2019 nonfiction book, Three Women, a masterful portrait of sexual desire and abuse. It’s as if she inhaled the cruelties her subjects endured in her first book and exhaled Animal’s protagonist, Joan. Taddeo told audiences at a May book event that while writing about “all the trauma, rage built up in me.” In Joan’s world, husbands always betray wives, and fathers their families; young women left alone fall prey to seedy men who are constantly circling. “Honestly, sometimes I think it’s the only recourse,” her friend Alice comments, “killing men in times like these.”

These stories offer a retributive vision of justice, the violence of the man mirrored back onto him. Traditional gender roles are flipped—the woman is the predator, and the man is the prey—but the basic shape of the conventional revenge story is unchanged. Witnessing women take revenge in film and fiction may offer a cathartic thrill, but the trope can also function as a trap; vengeance replicates the same power structure the avenger wishes to hold accountable.

Here we have a depiction of violation and redress suited to the way the country conceives of justice: The enemy must be rooted out and made to suffer in turn. This is the moral logic of films like Kill Bill, and it is also the moral logic of mass incarceration, which has done nothing to make us safer and certainly nothing to make sexual violence less ubiquitous.

But justice can and should mean something other than the balancing of harms, as prison and police abolitionists and other activists have argued. In resisting the carceral approach to punishment, they advocate a politics of structural change, of experimentation and openness to new social forms. These ideas demand a radical artistic approach to match, a breaking free of the traps of the revenge plot. A couple of recent works give us a sense of this. Call it the reparative mode.

Act II

Revenge

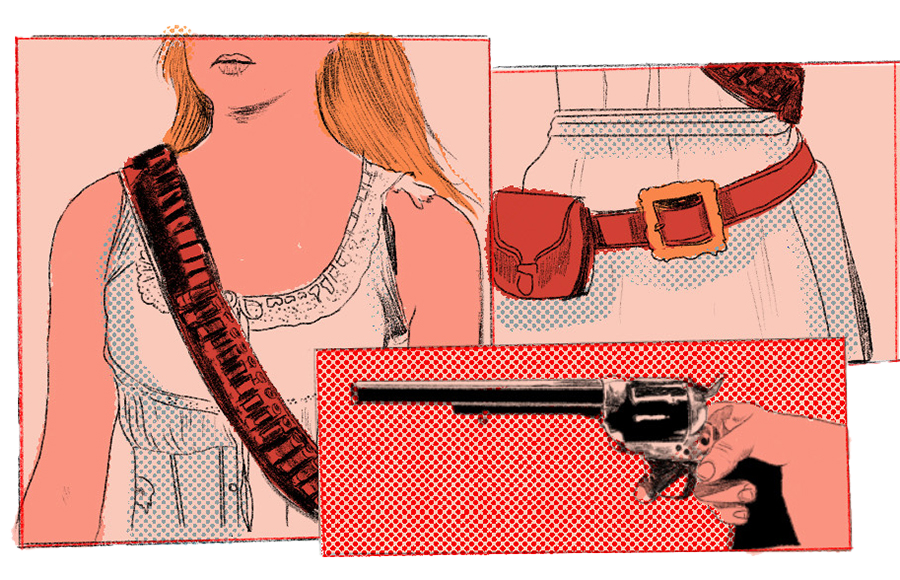

In the sci-fi TV show Westworld, humans enact their shoot-’em-up and sexual fantasies on semi-conscious AI robots programmed to depict stock characters from the 1800s Wild West. In the season 2 opener, the robot Dolores—a sweet rancher’s daughter turned vigilante after all the accumulated trauma—confronts some of the theme park’s board members, whom she’s taken hostage. “Did you ever stop to wonder about your actions? The price you’d have to pay if there was a reckoning?” Dolores asks, toying with a pistol as her blond hair streams behind her, a bandolier of bullets slung across her chest. “That reckoning is here.”

The line, arriving after Dolores has been violated and mutilated dozens of times, lands with a satisfying smack. And that’s often the case with watching revenge stories: They beckon with a sense of fairness, symmetrical closure; as the old saying goes, an eye for an eye.

The allure of revenge also lies in its potential to spark a personal metamorphosis. Dolores begins Westworld as a saccharine ingenue, but by season 2 has morphed into a confident killer. Promising Young Woman’s Cassie was just another eager med school student before she began weaponizing her femininity (and whiteness, as several critics have pointed out) to bait perverts. Animal’s protagonist, Joan, spent years acquiescing to slimeballs before finally suffocating one of them in his bed. Enacting revenge, these narratives hint, empowers women.

But is it empowerment? Westworld, like many controversial rape-revenge stories before it, spends an inordinate amount of time sensationalizing rape for the sake of entertainment. Its female avengers look suspiciously like the cowboys of testosterone-dominated Westerns. And their strength seems to have come about as a result of having been raped; their empowerment, then, relies first on their violation and then on their assuming the guises and behaviors of their assailants.

Emerald Fennell was likely aware of the exploitative tendencies of the rape-revenge genre when she released Promising Young Woman. As her film was making waves last year, Fennell told Variety, “We’ve seen this movie a billion times. Let’s then be honest with it.”

Fennell forgoes reenacting the central rape scene that fuels her protagonist’s transformation and instead focuses on the fallout of that transformation. Cassie’s obsession with revenge derails her career ambitions; it gets in the way of her relationships; it infantilizes her. She paints her nails the color of Starburst candies and drinks from a juice box.

After a betrayal pushes her over the edge, she ups the ante on her revenge tactics and—stop reading this if you care about spoilers—she ends up dead. If Fennell’s Cassandra was trying to deliver us a message, she is silenced before we can make out the words.

Revenge may corrupt as much as it empowers, these rape-revenge stories seem to say. Yet even as Promising Young Woman acknowledges the destructive nature of revenge, the film offers a limited conception of justice. In the film’s final scene, an outdoor wedding punctuated by a trail of blood-red rose petals, police sirens flood the air, and cops haul away Cassie’s friend’s rapist after he has said “I do” to a swimsuit model. Cassie gets her revenge in the end. It just comes by way of the police.

Act III

Transformation

One kind of rape-revenge story seeks to empower its heroine by handing her a weapon. A different kind gives her the tools to break free from the cycle of violence she is caught in. It does so by reimagining the very composition of the narrative that binds her.

“For centuries there’s been one path through fiction we’re most likely to travel—one we’re actually told to follow—and that’s the dramatic arc,” writes Jane Alison in her 2019 lit-crit book, Meander, Spiral, Explode. In this arc, Alison writes, “a situation arises, grows tense, reaches a peak, subsides.” Something that “swells and tautens until climax, then collapses? Bit masculo-sexual, no?” By adhering to this form, we remain caged in its patriarchal origins. Why not draw on other structures instead?

Alison’s book focuses on alternative fictional forms that mimic natural patterns. But I find her logic applicable to the rape-revenge narrative and its limitations. Rape, transformation, revenge: Will using this same tired formula provide a pathway to justice, or is it simply a route that leads to more destruction, even when the law steps in?

Michaela Coel’s 2020 HBO series, I May Destroy You, toys with this question as it probes the wreckage of sexual assault. Coel—who, in contrast to Fennell, had complete control over the work as its creator, co-director, executive producer, and lead actress—plays Arabella, a millennial author who is drugged and raped at a London club one night. (Coel had a similar experience in 2016.) Arabella wrestles with first acknowledging that the trauma even occurred, and then with how to respond, as her friends Terry and Kwame help her process the horrendous incident while reckoning with their own violations of consent.

In the show’s last episode, “Ego Death,” the narrative splinters into three alternate realities. The first scenario mirrors the classic rape-revenge plot: Arabella hatches a scheme to drug the man who raped her, and then ends up kicking his head in on the sidewalk and stuffing his body under her bed. In the next, Terry helps Arabella lure the man into the bathroom and then calls the cops on him, though not before Arabella has learned of his fragility and started to sympathize with him. The last scenario shows Arabella passionately hooking up with the man, even playing a dominant role in the seduction.

After each scenario, Arabella revises a notecard pinned to her wall, the pieces of a book she is composing. As she cycles through yet never clearly settles on these possible endings—violent revenge, extreme empathy, or sexual fantasy—her choice becomes a moot point. The transformation we’re witnessing is subtle but no less meaningful for it: Arabella is taking back the reins of her own story, and of her life.

Susan Choi’s 2019 novel, Trust Exercise, also incorporates a fragmentary, mazelike structure to destabilize our expectations of how sexual assault should be dealt with. Set at a performing arts school in a swampy Southern city in the 1980s, the first part of the novel focuses on 15-year-olds Sarah and David, caught up in a classically awkward teenage love story and lorded over by an intrusive drama teacher, Mr. Kingsley. Yet halfway through the action, the story fractures, and we’re introduced to Sarah’s friend Karen, who proceeds to recount her own version of the same events.

As this new story unfolds and fractures yet again, characters collapse into one another, the point of view seesaws between third person and first, and parallels emerge that undermine our sense of the truth. In a play within the play, Karen appears to take revenge on an older ex-lover playing the lead role, a guy who impregnated her and then disappeared when she was 16. But then the chapter ends, and the curtain closes. Was it just a fantasy?

Neither of these works offers a simple solution to sexual violence. Yet by defying traditional narrative structures, they urge a rethinking of the very forms they’re contained within. The result is an atmosphere of uncertainty and contingency, a resistance to pat answers. This is the reparative mode: It rejects the destructive reflex in favor of an openness to possibilities that have yet to be explored.

In this way, these fictional works echo the thinking of a set of activists who for decades have been advocating a response to sexual violence that does not perpetuate the same violence it seeks to redress. “The punishment mindset is very hard to get out of,” abolitionist activist and educator Mariame Kaba said in a 2018 interview about #MeToo on the podcast How to Survive the End of the World. The desire for vengeance is a healthy and normal reaction, she explained, but the use of violence as punishment doesn’t work. That includes violence in the form of revenge, and it also includes violence in the form of incarceration. “If we want to reduce (or end) sexual and gendered violence,” Kaba writes in her recent book, We Do This ’Til We Free Us, “putting a few perpetrators in prison does little to stop the many other perpetrators. It does nothing to change a culture that makes this harm imaginable, to hold the individual perpetrator accountable, to support their transformation, or to meet the needs of the survivors.”

Kaba and other practitioners of a modality called transformative justice—many of them steeped in Black radical traditions—focus on holding people who commit violence accountable within and by their communities. And they advocate addressing the root causes of crime to disrupt cycles of harm. “No one enters violence for the first time by committing it,” Kaba’s friend and fellow activist Danielle Sered once said. Violence is a feedback loop, a series of terrible symmetries. Rather than perpetuating its cycles through punishment, “it’s the harm that I’m interested in transforming,” Kaba explains. Doing so will require forgoing further punishment and withdrawing from prison and policing systems that act as systems of oppression—in other words, a complete transformation of the structures in place.

I May Destroy You offers a brief glimpse of what that world might look like. In several of the last episode’s alternate reality scenarios, Arabella pauses for some fresh air on her apartment’s rooftop. Her roommate asks whether she’ll be spending the evening at the bar where she was raped, hunting for the man who carried out the act. In the first couple iterations of this scene, Arabella says yes. But the last time we see the scene play out, Arabella ponders the roommate’s question and says “nah.” She then rises and gives her roommate a big hug. It’s a small gesture, but it signals a big leap: Rather than choosing retribution, she is surrounding herself with love.