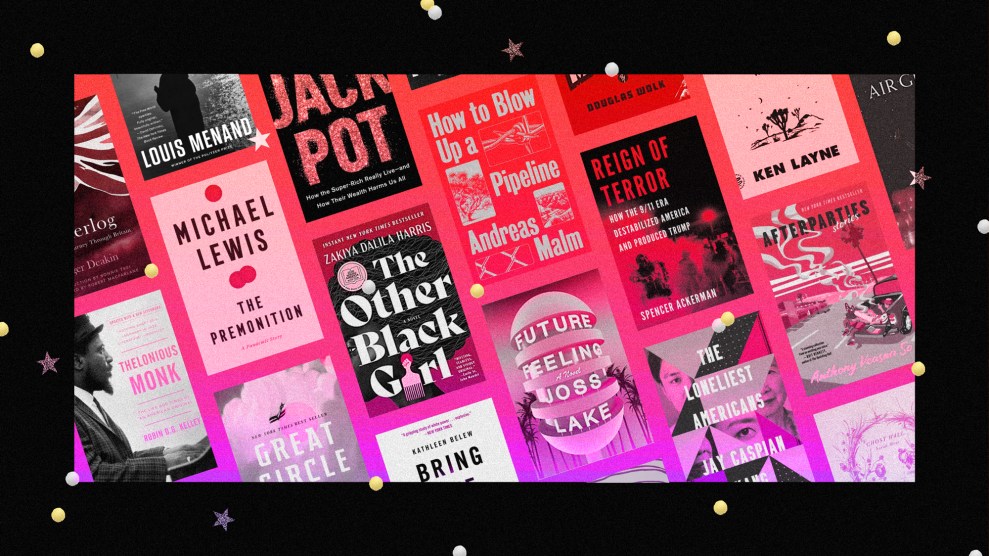

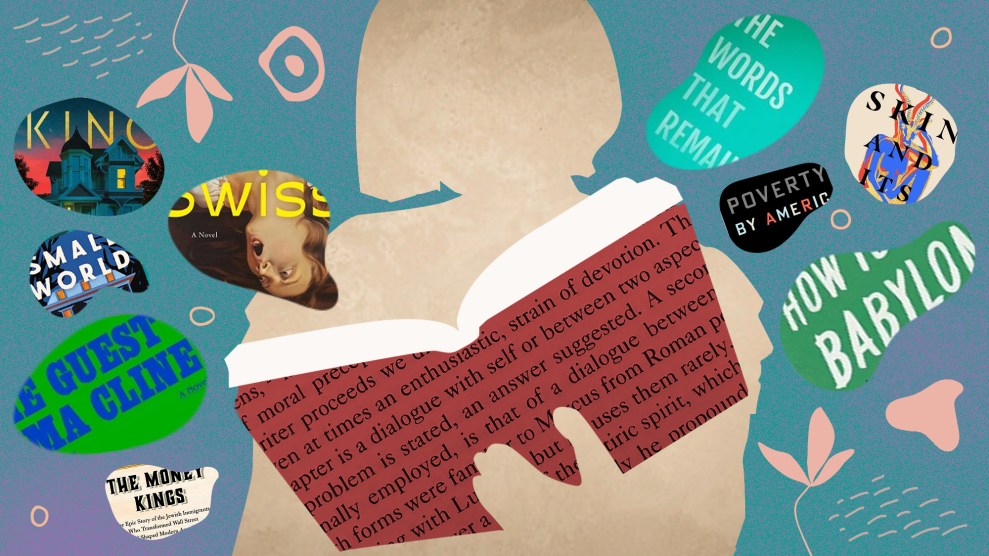

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Nonfiction

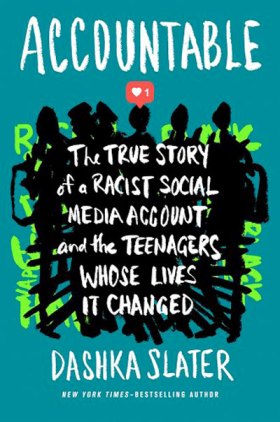

Accountable: The True Story of a Racist Social Media Account and the Teenagers Whose Lives It Changed

Nonfiction Accountable, like journalist Dashka Slater’s previous young adult bestseller, The 57 Bus, documents harrowing events in her own Bay Area backyard—in this case the town of Albany, near Berkeley, where an Instagram uproar turned an affluent, tight-knit community completely upside down. In 2017, an Asian American student at Albany High whom Slater calls “Charles” created this private account, which was followed by 13 other white or Asian classmates. Charles soon began posting a series of “edgy” items, including racist memes targeting Black female classmates. There were misgivings, of course, but amid the complex group dynamics and teen social anxieties, none of the others confronted Charles or unfollowed the account—some kids even “liked” the awful posts. Such things never stay private, of course. When word got out, anger and chaos ensued—and the defensive responses of parents and administrators only made matters worse. Accountable is a useful case study for any community facing this kind of online blowup, which Slater assures me is “shockingly” common. Her close access to key players offers a nuanced and intimate window into an incredibly thorny situation. Written in a style accessible to teens, the book is no less valuable for adults, as it challenges our instinctive views about punishment and accountability, and our human tendency to rush to judgment. —Michael Mechanic

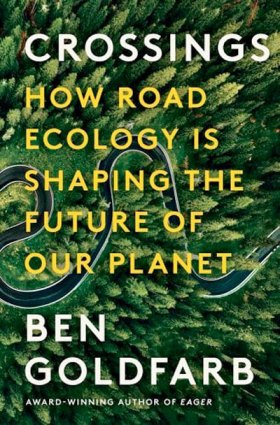

Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet

Nonfiction I’m giving everyone this book for Christmas. It’s about roadkill.

Crossings should change the way we look at something we take very much for granted: roads and the animals flattened on them. Goldfarb shows how even lightly traveled highways in the middle of nowhere can irreparably destroy the migration and reproductive patterns of all sorts of animals, from moose to butterflies. He traveled the globe to see how countries have reckoned with the mass slaughter taking place on the asphalt ribbons chopping up large expanses of undeveloped land. Some of the most innovative solutions come from developing countries like Brazil, which has pioneered infrastructure to help the chicken (or in this case anteaters) cross the road, so to speak, even as it paves over the rainforest. Often the goal of road ecology is to prevent car accidents and keep traffic moving, but it has unexpected benefits. Goldfarb writes about my home state of Utah, which installed a wildlife crossing over I-80 in Parley’s Canyon that proved surprisingly popular with both people and hundreds of animals. What I loved most about this book are its unsung heroes, like the volunteers who carry buckets of toads across a road during spring mating season to prevent “mass squishing” events. It’s often a completely lost cause, but Goldfarb paints roadkill prevention as a moral response to the “sixth extinction.” You have to love a writer who cares deeply about squashed toads, so make his book this year’s stocking stuffer. —Stephanie Mencimer

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy

Nonfiction In the narrowest sense, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama is about what happens when, en route to an amusement park outside of Jerusalem, a school bus filled with Palestinian children—one of them five-year-old Milad Salama—crashes with a truck that jackknifes. His father, Abed, joins the rest of the parents in the frantic attempt to find their kids, who have been sent to different hospitals in Jerusalem and the West Bank. But the crash creates the opportunity for a vivid picture to emerge of the occupation’s outcomes: Fire trucks don’t arrive soon enough, EMTs are unavailable, Bedouins create a bucket brigade to extinguish flames. The children are restricted in which hospitals they can enter, and their frantic families struggle to figure out where to go and how to get there given all the Israeli checkpoints they must cross. With Abed’s story as the centerpiece, Thrall focuses on a few of the families, providing the backstory of the couples’ courtships, and how tensions among them play out as they try to save their children. His richly textured retelling, also involving Jewish first responders and Arab Israeli hospital workers, depicts without a didactic moment the fraught realities of life in a divided society. Detailed maps show the specifics of roads, the checkpoints, and the difficulty of being a Palestinian in the West Bank during a crisis, and even when life passes for normal. Published only days before the Hamas attack focused a global spotlight on the region, Thrall’s revelation of the enormous complexity on the ground could not be more timely. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

The Hank Show: How a House-Painting, Drug-Running DEA Informant Built the Machine That Rules Our Lives

Nonfiction After reading this fascinating book, I can no longer countenance people talking about how America is turning into a surveillance state. Too late, I’ll say. Privacy was dead and buried ages ago. Funk, a talented magazine journalist, chronicles how the late Hank Asher—brilliant, obsessive, and volatile—pioneered the business of harvesting every available scrap of information about every American back in the early 1990s. These snippets, including court and DMV records, residence addresses, data about our travels, families, relationships, professional pursuits, money owed, consumption habits, social interactions, and more, resided in far-flung public and private databases. Asher’s innovation was to gain access to these disparate troves and merge them into a single, high-speed storage-and-retrieval system that knew more about us than we knew about ourselves. To win over high-level clients, including law enforcement brass who presumed their information was sacrosanct, he only had to run the person’s name through his system. The universe of data services he unleashed, now peddled by firms like LexisNexis, Equifax, and Cambridge Analytica, can be put to good uses—like improving health outcomes and nabbing child abductors—but also deeply problematic ones. Readers will learn how Asher’s work likely cost Al Gore the presidency in 2000, and how police and immigration authorities used his products to seize and deport otherwise law-abiding immigrants with American-born children. This deeply reported book is required reading for people who want to comprehend American culture and where it’s headed. —Michael Mechanic

How to Say Babylon

Nonfiction “Look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King, he shall be the Redeemer,” declared the legendary Pan-African leader Marcus Garvey in 1920. These words would launch the Black equivalent of a thousand ships and give birth to Rastafari, a religious movement that would spread its vision of Black liberation and pride—not to mention its famous reggae songs— to every corner of the globe. Decades later in the 1990s, this was the world in which Safiya Sinclair grew up in Jamaica. She was the perfect Rastafari daughter, following her unlucky musician father’s strict Rastafari rules, diet, and unwavering belief in the Black messiah, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. She dedicated herself to her father’s crusade against “Babylon,” the capitalist, racist forces conspiring to “destroy the Black man.” But as Sinclair comes into her own as a woman and a poet, she watches the Rasta women in her life and wonders how a religion grounded in freedom can demand their silence and submission. She loses the love and care she enjoyed when she was a child. Her father comes to see her as an agent of Babylon’s corrupting ways, setting them on a collision course that will change their family forever. With lyricism and moral clarity, How to Say Babylon is a treatise on who gets left behind in the pursuit of liberation. Sinclair’s questions will send her on a journey through her family and Jamaica’s painful yet beautiful history. In the end, Sinclair reminds us that while the urge to dominate might be an inherited trait, so too is the desire to be free. —nia t. evans

The Money Kings: The Epic Story of the Jewish Immigrants Who Transformed Wall Street and Shaped Modern America

Nonfiction Zionism, antisemitism, immigration, and conspiracy theories of the right—in The Money Kings, Daniel Schulman tackles issues that confront us today but in a narrative that occurred over a century ago. In this masterful group biography of Jewish immigrants who arrived in the United States in the mid-1800s and rose from merchants and commodities traders to titans of American finance—such men as Jacob Schiff, Emanuel and Mayer Lehman, Marcus Goldman, and Samuel Sachs—Schulman tells the intriguing tale of how these outsiders helped build America by constructing its financial system, as they forged their personal empires in the Gilded Age of robber barons and railroad magnates. Each of their stories is fascinating. But Schulman, an editor at Mother Jones, goes beyond these individual accounts to show us that controversies that grip the world today have been around for a long time. One example: Schiff, a tycoon who in the early 1900s was the leader of the American Jewish community, fiercely opposed Zionism, believing it would undermine the acceptance of Jews in the United States, especially as the number of Jewish immigrants to the US, who were fleeing pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe, dramatically swelled. The Money Kings is history at its best, showing how the past shapes the present and providing us with the perspective needed for understanding the current moment. —David Corn

Poverty, by America

Nonfiction There are hundreds of nonfiction and fiction books that show us what poverty looks like—Charles Dickens immediately comes to mind, as does Barbara Kingsolver’s excellent Dickens adaptation, Demon Copperhead (scroll down for our review). Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond, who won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction for his last book, Evicted, and whose own family struggled financially during his Arizona childhood, chose instead to focus on why: Why is poverty—especially deep poverty, a ghastly state of existence for 1 in 18 Americans—so stubbornly persistent? In this enlightening and well-argued book, Desmond examines the reasons Americans face destitution at rates so much higher than, for example, Europeans. He also offers solutions and calls upon not only policymakers but everyday people of privilege to acknowledge our complicity—indeed, to remake ourselves as “poverty abolitionists.” We have the resources to eliminate this scourge, this national embarrassment, Desmond writes. It’s surprisingly cheap, and we know what has to be done. We need only to summon the heart and the will. —Michael Mechanic

We Were Once a Family: A Story of Love, Death, and Child Removal in America

Nonfiction You may remember the harrowing headlines: A white lesbian couple, Jennifer and Sarah Hart, drove themselves and their six adopted Black children off a California cliff in 2018. News coverage focused on the family’s tumultuous home life that they had camouflaged with charming Facebook posts and the Harts’ repeated insistence that they saved their children from what would have been otherwise impoverished upbringings. But Roxanna Asgarian, a freelance journalist who covered the murders for the Oregonian and the Appeal from the beginning, reveals the untold part of this story: how systemic failures of the so-called child welfare system made the murders possible. Asgarian reports on how the children—made up of two different sibling groups of 3 kids each—were yanked by child protective services from extended family members who fought desperately to keep them. Instead, they were delivered to the Harts’ doorstep, despite repeated red flags—including allegations of child abuse—about the couple’s fitness to care for the children. Asgarian avoids excessive speculation of the perpetrators’ psychology and potential motivations to unearth a deeper story, about how the women’s white privilege helped them avoid scrutiny, the inadequacies of systems that placed the children in harm’s way, and the anguish of the grieving birth families whose efforts to protect them were constantly thwarted. This book offered a masterclass in deeply empathetic reporting in the face of tragedy, and made me think about how sometimes, the real story is the one nobody else is telling. —Julianne McShane

Fiction + Poetry

Above Ground

Poetry How lucky am I? The year I first became a parent, the universe nudged Clint Smith to publish his latest poetry collection on the wonders and anxieties of fatherhood. Smith is a writer for the Atlantic and the author of the incredible How the Word Is Passed, a part-travelogue, part-memoir, part-investigation into how Americans remember and tell the story of slavery at different sites around the country. But he was a poet first, and he returns to those roots for a crystalline exploration into how becoming a father rearranged his world. The verses trace the achingly long lead-up to birth and the subsequent unfurling of a family. Smith meditates on ancestry and the worrisome world his children are born into, and delivers odes to baby milestones and contraptions, from hiccups and bedtime to the electric swing. I came for the lyrical observations of parental love—and my arms are still/ open like a universe/ in need of a planet/ to make it worth/ something, he writes in “Ode to the Bear Hug”—and stayed for Smith’s reverence for his partner, the mother of his children, which is layered into nearly every page and must have satisfied my new-mom craving for recognition. At the doctor’s office, Smith writes in “Trying to Light a Candle in the Wind,” I place the small headphones/ in my ear and listen as you somersault back and forth/ between the walls your mother built for you. —Maddie Oatman

Big Swiss

Fiction The titular character of Big Swiss has had enough of the trauma people. “Trauma people are almost as unbearable to me as Trump people. If you try suggesting that they let go of their suffering, their victimhood, they act retraumatized,” she tells her sex coach/therapist. Unbeknownst to Big Swiss, one of those “trauma people” is listening in on her session. Greta works for the therapist, transcribing recordings of his sessions. She has a dark past she holds onto tightly, and is immediately mesmerized by Big Swiss, who isn’t in therapy to discuss her own trauma (a horrific beating she insists she never thinks about), but because she’s a married 28-year-old gynecologist who has never experienced an orgasm. Consuming Big Swiss feels less like reading and more like rubbernecking when Greta meets Big Swiss in real life and, instead of distancing herself, becomes deeply entangled in her life (and mind and body). All the while, Greta continues to listen in on Big Swiss’ therapy sessions, in which she becomes a central subject. Big Swiss is hilarious, engrossing, and fucked up in the most delightful way. The tensions Beagin draws between characters, but also within them, are fascinating to follow—I wanted to know everything about Greta but would never want to know her, while I found myself quickly oscillating from envying Big Swiss to pitying her. For a book with such darkness within, this was a terribly fun read. —Ruth Murai

Forbidden Notebook

Fiction In Forbidden Notebook, originally published in Italian in 1952 and released in English translation this year by Ann Goldstein, Elena Ferrante’s translator, Valeria Cossati’s black notebook represents an act of resistance. She procures it secretly, on a beautiful November Sunday in 1950, as Rome reels from a paper shortage. From that moment, the notebook becomes a repository for Valeria’s hidden desires: to transcend the gendered injustices of her own family, who largely expect her to sacrifice her thoughts and desires at the altar of domestic duties. Her husband infantilizes her; her daughter defies—and intimidates—her, and her son’s budding misogyny repulses her. It’s writing that helps her understand how limited her roles as wife and mother make her feel, and how her notebook, and a burgeoning love affair, are her only forms of freedom and excitement. But as liberating as those realizations are, facing the truth isn’t the same thing as actually changing one’s life. “All women hide a black notebook, a forbidden diary,” our protagonist writes. “And they all have to destroy it.” If you’re a Ferrante fan, you’ll likely love de Céspedes’ piercing prose, as it probes the inner lives of women searching for meaning in a patriarchal Italian culture and facing the distance between who they’ve become and who they’d like to be. —Julianne McShane

The Guest

Fiction The Guest follows a common beach-read blueprint in that it concentrates on a hot young woman in a sumptuous setting. But that’s about where the comparisons end. You definitely don’t want to be the main character, Alex, a 22-year-old sex worker trying to escape debts and an ominous man back home by summering in the Hamptons with Simon, an older, exorbitantly wealthy man who sends her packing early in the novel. You really don’t even want to know Alex. Welcoming this hot-mess express into your palatial beach house as she tries to work her way back to Simon might mean she crashes your car, takes advantage of your suicidal teenager, or borrows your young child to ascertain free drinks. She will absolutely lie about who she is—to you and to herself. Somehow, a broke girl with enough wits to finagle accommodations for six days in an elite vacation destination is delusional enough to think she can win Simon back a week after embarrassing him at soiree where, as his guest, she took an unsanctioned night swim with the host’s husband. Yet even as you, the reader, are begging Alex to get her shit together, you are also sympathizing with this homeless, friendless vagabond, whose grifting was almost certainly borne of some sort of trauma. So, while not the typical beach read, The Guest does serve as a respite from one’s own stresses in exchange for a dose of someone else’s more chaotic ones. And as is often the case with real-life vacations, you’ll be glad you visited Alex’s brain, but wouldn’t want to live there. —Abby Vesoulis

Holly

Fiction At the end of September, I came down with Covid for the first time and was miserably sick for two weeks. Bedridden, I couldn’t focus on a book or TV for long. But I was bored, so I decided to close my eyes and have someone read me a story. Audible recommended Stephen King’s latest, Holly. I hadn’t read a King novel since Cujo in high school. Horror is not my thing, but Holly is one of King’s detective novels, which are my thing, so I took the plunge. After spending some time knocking around inside King’s brain, I learned what his fans probably already know: Stephen King is one sick fuck. But the master of horror is also a master of character development, and Holly Gibney is a good one. A sort of neurodivergent, accidental detective, Holly falls into a missing person’s case that is horrifying, but not in a Carrie kind of way. King, now 76, deftly deploys the fear of aging to move the plot in unexpected directions. It was somewhat unsettling to read a book that takes place against the backdrop of Covid while suffering from it. (Holly’s unvaccinated mother dies from the virus.) The Audible reviews indicate that King has infuriated some of his Trump-loving fans with this look back on the pandemic. But don’t let the reviews deter you: Holly is great, if occasionally gory, fun.—Stephanie Mencimer

Pineapple Street

Fiction In Pineapple Street, Jenny Jackson, who has spent a career editing bestselling novels, sets her sights on the upper crust of her own Brooklyn Heights neighborhood. At the center of her delightfully Jane Austen-esque debut is the Stockton family, whose real-estate wealth has accumulated over the course of several generations. The Real Housewives these are not: think wood-paneled private social clubs, not gilded McMansions. The story is told from the point of view of two millennial Stockton daughters—erstwhile finance industry consultant-turned-stay-at-home-mom, Darley, and her party-girl kid sister, Georgiana—and Sasha, who has recently married their brother, Cord. Sasha, who grew up working class in Rhode Island, finds herself living in the family’s sprawling home, trying to make space for herself amid all their junk—er, heirlooms. No matter how hard she tries, she can never manage to fit into the rarefied world of her new family—her raucous cousins crash her wedding, she hosts a dinner without properly decorating the table, she wears black and white to her in-laws’ party and is mistaken for a maid. Her transgressions do not go unnoticed by her sisters-in-law, who are convinced she’s after their fortune and call her “GD” (gold digger). In turn, whenever the Stocktons do something inscrutable, Sasha and Darley’s husband mutter “NMF” (not my family). The drama lies in the fact that they’re all wrong. Pineapple Street is a great send-up of rich people, but it’s more than that. Jackson’s characters are privileged, but not one-dimensional buffoons (with the possible exception of matriarch Tilda, who gives off real Mrs. Bennett vibes). Rather, they are complicated, funny, thoughtful, and likable, and it’s that humanity that had me listening to the audiobook deep into the night, devouring all the delicious details, plot twists, and coming-of-age revelations. —Kiera Butler

The Sense of Wonder

Fiction This May, I wept through Connie Wang’s New York Times feature story about a generation of Asian women (including herself) named after iconic CBS News anchor Connie Chung. “We saw Connie,” one of the mothers explains. The idea of so many Asian women really seeing Chung, and thus themselves, moved me deeply. I was thinking of those women and their mothers and Connie Chung when I read this excellent novel from Matthew Salesses, a fictional version of Taiwanese basketball player Jeremy Lin’s meteoric rise to stardom in 2012. Lin gave us “Linsanity”—Salesses gives us “The Wonder” through his protagonist, Korean basketball player Won Lee who, like the real Lin, leads a winning streak for the New York Knicks that catapults him to fame. Alongside Won is producer girlfriend Carrie Kang, who is trying to bring K-dramas to an American audience. Rumor has it Won, overlooked for his entire career, was only signed by the Knicks to sell jerseys to the New York Asian community. With this as his frame, Won grapples with how his successes and eventual mistakes might be experienced by people in his community and judged by outsiders. Carrie, meanwhile, struggles to introduce a Korean genre to a judgemental audience. “To be a minority in America is to guard what you love against other people’s scorn,” she muses. The Sense of Wonder is funny, bright, and full of energy. The feelings it evoked brought me to tears, much like the Connies did. In Won, in Carrie, and even in their foes, I felt seen as an Asian American. If that all weren’t enough, the novel’s genuinely surprising and delightful final paragraph is worth reading the whole thing to get to. —Ruth Murai

The Skin and Its Girl

Fiction Moments after Betty Rummani is born, she begins to turn blue—not the pallid tone of death, but “the pure cobalt of a gas flame,” like a “creature from a fairy tale.” At the same time, halfway across the world, fighter jets release bombs over the West Bank city of Nablus “in retaliation for some offense,” obliterating the olive oil soap factory that had once belonged to the Rummani family for generations. In this luminous novel, Betty retraces her family’s path from Palestine to the United States, piecing together love affairs, betrayals, and abandonments as she struggles to figure out whether to follow her own lover overseas. Much of the narrative comes in the form of Betty’s address to her Aunt Nuha, a firecracker of a character, who hid her sexuality from her family even as she kept so many of her ancestor’s stories alive. Cypher incorporates Palestinian history and remakes myths and Biblical tales, like the Tower of Babel, to examine how storytelling creates society. While she couldn’t have predicted it, her book lands at the right time: The recent crises in Israel and Gaza have deepened rifts among communities the world over. I was grateful to turn back to a complex, multilayered novel like this one, which caused me to meditate on the role of erasure in the stories we think we know. —Maddie Oatman

Small World

Fiction The death of a young sibling haunts a family. And if the child was seriously ill or disabled before passing away, surviving children often experience something called “Well Sibling Syndrome.” Laura Zigman’s oldest sister Sheryl, physically and developmentally disabled from a rare bone disease, was institutionalized when she was two years old and died five years later. After Sheryl’s death, Zigman wrote in an essay, she and her sister spent their childhood and adolescence feeling “profoundly alone.” In Small World, her sixth novel, she spins this rough outline into the mordantly funny and deeply moving account of the middle-aged Mellshman sisters, Lydia and Joyce (the narrator). Their middle sibling, Eleanor, had been born with cerebral palsy and a seizure disorder and died a year later. Unlike the Zigmans, the Mellishman family disintegrated. Fast forward to Lydia moving into Joyce’s not-large apartment after her divorce and all the tensions and regressions involved in adult siblings cohabitating—eating out of take-out containers in the kitchen—while coping with their long-repressed family tragedy. The local listserv “Small World” is one of Joyce’s secret obsessions, a Nextdoor-style compendium of neighborhood outrages, warnings, and injuries that she hilariously reorganizes and re-punctuates into her own free-verse poetry. (I can no longer look at my own neighborhood’s postings anymore without creating little Haikus.) In a year like 2023, I welcomed the chance to get lost in this compulsively readable novel and be drawn into a poignant family drama of remembrance, recrimination, and uneasy reconciliation, leavened by Zigman’s psychological acuity and capacity to reveal the unforgiving absurdities of intimacy. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers

Fiction This mystery is the perfect easy, cozy read to get you through long winter nights. It centers around Vera Wong, an old Chinese woman who runs a sleepy tea shop in San Francisco. One day, her world is turned upside down when she finds a dead man in her store. A classic whodunit follows. There are bungling cops, a determined protagonist, a crew of suspects with secrets that may or may not implicate them in the man’s death. Sutanto manages to combine these tropes into a charming final product that should please mystery fans while also reaching readers new to the genre. Its gentle message about the importance of love, food, and family feels particularly apt for the holidays. And the denouement proves the cleverest mystery isn’t always the goriest or cruelest. —Sophie Hayssen

The Words That Remain

Fiction Brazilian Stênio Gardel’s debut is the winner of this years’ National Book Award for translated literature. Originally published in Portuguese in 2021, this heartbreaking account of queer desire and resilience introduces readers to Raimundo Gaudêncio de Freitas, an illiterate man in Brazil’s hinterland who was deprived of education, and thus the chance to read the words of Cícero, the long-lost, forbidden love of his youth. His father’s rage and past traumas push Raimundo out of the house and away from the family. For more than 50 years, he carries Cícero’s unopened letter “half-blessed, half-cursed, wholly mysterious,” until, at the age of 71, he finally learns how to read and write. Gardel draws in part from his own experience as a civil servant for the Brazilian Electoral Court, where he assisted illiterate voters, to explore the power of the written word, and the themes of prejudice, violence, and marginalization. His poetic writing style, powerful use of stream of consciousness, and alternating perspectives creates a hopeful yet agonizing read, in the sense that it’s not always clear where the narrative ends and the dialogue begins. The effect was that the deluge of raw emotions and memories on the page started to feel like a reflection of my own. —Isabela Dias

Nonfiction, Fiction, + Poetry published before 2023

Babel, or The Necessity of Violence (2022)

Fiction Power comes from words, quite literally, in R.F. Kuang’s Babel. In this alternate reality British Empire of the 1830s, people derive magic from translating between two languages. When the well of European languages run dry, the British turn to the more exotic languages of their colonies. The story follows young scholars from China, India, and Haiti whisked away to Oxford to study at the Royal Institute of Translation, nicknamed “Babel.” The empire requires their brains, their words, their histories, and their cultures; in return, the teens get access to education, riches, and opportunities they would never have been afforded back at home. The deal is impossibly tempting but the consequences are increasingly high, as it becomes clear that the scholars are using their mother tongues to fuel a machine that is trying to control their home countries. Going beyond metaphor, Kuang makes tangible forms of extraction that do not leave visible scars. In a world mired by visible violence, Babel asks us to contemplate the violence that is slow, subtle, structural, and easily ignored—and what is required to stop it.—Henry Carnell

Demon Copperhead (2022)

Fiction Kingsolver has said she wrote Demon Copperhead, her Pulitzer Prize winning 2022 novel about an orphan growing up in southwestern Virginia, to tell the story of the opioid epidemic in Appalachia and address coastal elites’ condescension to rural Americans. She did that by adapting Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. That makes her book didactic, derivative and pretty sentimental, which you might think means not that good. But while the book may have an excess of lectures about America’s poor treatment of Appalachians, it is riveting because Kingsolver is a matchless storyteller who ingeniously deploys a key thing she took from Dickens. Like Copperfield, Kingsolver’s hero is a child describing loss, along with neglect and exploitation by adults. The resulting dramatic irony—we feel we understand what is occurring better than him—helps us feel for him. And if Demon’s perspective (all the young characters have nicknames) owes a lot to Dickens, his voice—funny, regional, and resilient—is Kingsolver’s inspired invention. So are the book’s best scenes, like the one in which Demon and his friend Swap-Out sort trash and dodge rats outside what appears to be a meth lab under the watch of Indian-American mini-mart owner Mr. Golly, a decent guy despite his evident reliance on child labor and drug revenue. Set in the 1990s at the outset of the opioid epidemic, the book is affecting because we know where the characters’ world is heading, and we care about them. Demon Copperhead is fine as social commentary, but it’s art because it’s so sad. —Dan Friedman

Everything I Need I Get From You: How Fangirls Created the Internet As We Know It (2022)

Nonfiction In 2023, the power of fandom was on full display. Swifties’ outrage over Ticketmaster glitches led to a Senate hearing in January. Along with Beyoncé’s fan base, the Beyhive, Swifties also may have helped America fend off a recession this past summer, proving that girls really do run the world. Author Kaitlyn Tiffany, a writer for the Atlantic, unpacks the ascent of online fandom during the 2010s, using the now-defunct British boy band One Direction as a case study. The book is generally an easy read with lighthearted anecdotes about young girls going the extra mile for the stars they love—an entire chapter is dedicated to the shrine fans built at a roadside spot where Harry Styles threw up. Yet Tiffany also tackles the darker side of the Directioners (One Direction fans), including their conspiracy theory that Styles is in a queer relationship with former bandmate Louis Tomlinson. The book is not only important for understanding culture and technology, but it acts as a tangible record of online subcultures whose existence are under threat. It would be near impossible to critique pop culture without some understanding of how these so-called stan communities function, and for that aspect especially, this book is a must-read. —Sophie Hayssen

Fear of Falling (1989)

Nonfiction Reading nonfiction books published before 2000 can be a numbing experience. They always seem to accurately predict our future and warn us of the dark path we’re on, and we seem to mostly ignore those warnings. I’ll look up from the page about worsening trends in inequality, or the troubling resurgence of white supremacists, and think about how I’m living in an inferno that was predicted 20 or 30 years ago. Barbara Ehrenreich’s entire corpus probably works like this, especially Fear of Falling, her 1989 history of the middle class and prophecy of its fall that deftly straddles the lines of academic thoroughness and readability. Even after 33 years, the book remains elucidating as it tracks how the avarice of the 1980s gutted the lower class and was starting to chip away at a then-solid middle class, and contextualizes the anxiety of a bourgeoisie that could already sense its fate. Ehrenreich, who passed away last year, helped show us that our reality is a constructed one, and that we are capable of constructing alternatives. Fear of Falling pairs well with her best-seller Nickel and Dimed, a first-person ethnography of the working poor, and her 2013 essay, “Death of A Yuppie Dream,” which updates her 1989 observations. —Ali Breland

First Four Books of Poems (1995)

Poetry In July, just before Louse Glück died—and three years after she won the Nobel Prize in literature—I texted my friend a poem from this collection and asked whether she also thought “Gretel in Darkness” was horrifically cringe. We came to an agreement: It is an embarrassing poem. But I couldn’t help but admire it: Glück tried. In First Four Books, we can see one of America’s most accomplished poets searching for higher meaning in an inner voice that isn’t necessarily saying things that the rest of the world would deem serious—not at first glance anyhow. Glück’s art would be in finding a way to convince us her voice mattered. This year, reading poetry when my mind is too frazzled to focus, I have been thinking of how our internal voices are so often embarrassing yet true. How many of our innermost (and often most acutely felt) anxieties are stupid? Reading these poems, some total failures and others soaring, I came to respect Glück for her effort to make something as silly and profound as love show up on the page as serious art. (A love poem, as an adult—what a daring attempt!) In her Nobel speech, Glück said she believed the committee was honoring “the intimate, private voice which public utterance can sometimes augment or extend, but never replace.” In this book, you can begin to see how that voice is formed. —Jacob Rosenberg

Housekeeping (1980)

Fiction In the quiet beauty of Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson creates a world in which women are invited to step into the loneliness that lies outside the traditional bounds of society. The story centers around Ruth, a young girl who, after her mother dies, ends up living in a small town called Fingerbone. She and her sister are placed in the care of their Aunt Sylvie, a gentle misfit who’s lived for years as a nomad, sleeping in train cars traveling up and down the country. To create a home for her nieces, Sylvie tries her hand at this strange task—housekeeping—in this domestic realm that makes no sense to her, where there are neighbors to worry about and social expectations to meet. This isn’t easy for Sylvie, a lifelong transient who naps on park benches, serves cold dinner in the dark, and keeps the windows open for the crickets’ and nighthawks’ song. Over time, her eccentricity begins to drive a wedge between Ruth, who finds a sense of freedom in her aunt’s untamed spirit, and little sister Lucille, who yearns for a more conventional life. In a story as tender as it is gorgeous, Robinson gifts her characters with a rich inner wilderness that’s impossible to forget. —Nina Wang

Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival & Hope in an American City (2021)

Nonfiction I have recommended Invisible Child far and wide since reading it earlier this year. (It’s even in my dating app profile!) This stunning work of nonfiction by New York Times reporter Andrea Elliott, a winner of two Pulitzer Prizes—one for this book—is based on the nearly a decade she spent chronicling the life of Dansani, a young girl growing up in New York City, falling in and out of homelessness as her family struggled to improve its lot. Elliott’s deep access, coupled with her empathy, allowed her to document the injustices, big and small, that family members endured by virtue of being poor, Black, and ensnared in the legal and foster care systems. Her research into generations of Dasani’s ancestors, and exposing how New York City became such an unequal place, demonstrates the ways centuries of systemic racism have shaped contemporary poverty. By positioning a child as her protagonist, Elliott dismantles moralistic narratives about inequality that persist on the right, focusing instead on the everyday experiences of millions of children impoverished through no fault of their own. She also shows us how well-intentioned efforts to tackle child poverty—which often involve removing kids from their families and communities, including in Dasani’s case—fall short. What would it take, she asks, to create a world where every child gets the chance to thrive on their own terms? —Julianne McShane

Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative (2022)

Nonfiction As an editor, I spend a lot of time thinking about storytelling—my job involves helping reporters make sense of a set of discrete facts and distill them into a clear narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. But lately, I’ve been feeling increasingly anxious about journalists’ role in reducing the incredibly complex experiences of our subjects into tidy narratives. So it was a relief to see that ambivalence captured in this book by literary critic Peter Brooks, which explores the “use and abuse of narrative” in literature, politics, psychoanalysis, and the law. (He doesn’t spare journalists either: “The media proclaims storytelling everywhere, as if that were the only form of understanding left in civilization.”) Brooks argues that our culture has become narrative-obsessed—it’s hard to find a company that doesn’t have an “our story” page on its website, he points out, or a politician who doesn’t argue by anecdote. Brooks isn’t anti-narrative, but he does want us to take a critical look at the role storytelling plays in our lives, and to ask ourselves what our fixation with narrative might leave out or oversimplify. This may sound like heady subject matter, but the book is accessible, direct, and concise, pitched more at a general audience than an academic crowd. It’s also full of really smart close readings of works ranging from Henry James’ The Golden Bowl to a George W. Bush speech. “Story is powerful,” Brooks concludes. “And for that reason it demands a powerful critical response. We need to dismantle and contest its claims to totalistic explanatory force.” —Sophie Murguia

The Sellout (2015)

Fiction It’s 2015. Obama is in his final term, Donald Trump is commencing his diabolical ascent, Covid and George Floyd are on the distant horizon, and author Paul Beatty is the first American to win the prestigious Booker Prize for this mind-blowing satire on race in America. “So much happens” in this book, writes New York Times critic Dwight Garner, “it is like trying to shove a lemon tree into a shot glass.” Beatty’s narrator is a young Black man whose first name is never revealed but whose last name is Me. He lives on the outskirts of Los Angeles (Dickens, California) with a slightly unhinged social scientist single dad determined to raise his son with heightened race consciousness. (Allowance is “restitution.”) After Me’s father is murdered by the police, his son decides the best path to Black liberation and excellence is reinstating segregation—a plan that, oddly enough, includes enslaving an old family friend, Hominy, the last surviving Lil Rascal, who is eager to prostrate himself before his new master. Our narrator ends up before the Supreme Court—in the case Me v. United States of America—for having violated the Thirteenth Amendment. When a page is not crammed with laugh-out-loud observations, it is also fearless in taking on a litany of stereotypes and forcing the reader to look, shamefaced, in the mirror. I came to this book late, and it’s not for the fainthearted—the n-word appears relentlessly. But with divisions and tensions in our society feeling especially immovable, Beattie’s brilliant writing, subversiveness, audacity, wisdom, and (oh yes!) hilarity offers something close to a feeling of catharsis. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

When McKinsey Comes To Town (2022)

Nonfiction It is difficult to read this thorough history of the bleached white shoe consulting firm McKinsey & Company and not wonder if the company’s continued, unreformed existence constitutes a public policy failure. The two New York Times’ reporters establish the company as a Forest Gump-like figure of American industry malfeasance; in the biggest moments of the domestic economy and industry buckling over the last century, McKinsey is frequently sitting somewhere in the background of the shot. The spread of Oxycontin? McKinsey advised Purdue Pharmaceutical. Deaths at Disney parks? McKinsey was brought in as an advisor. The astronomical explosion of CEO compensation packages, which has played a role in historic American wealth inequality? Yes, McKinsey was stalking in the background of this as well.

McKinsey is not the sole force for all that is bad in a modern economy that has produced more for those at the top of the economy at the expense of those below. But Forsyth and Bogdanich show us how “The Firm” can be thought of as an elite, special forces commando unit spearheading these trends before the corporate foot soldiers of the Fortune 500 follow closely behind. Things that companies maybe would have liked to do, but could not bring themselves to do, like launching mass layoffs in service of better bottom lines for shareholders, were shuffled along by McKinsey for a handsome fee initially fronted by C-suites, but paid, in the end, by the rest of us. —Ali Breland

If you buy a book using our Bookshop link, a small share of the proceeds supports our journalism.