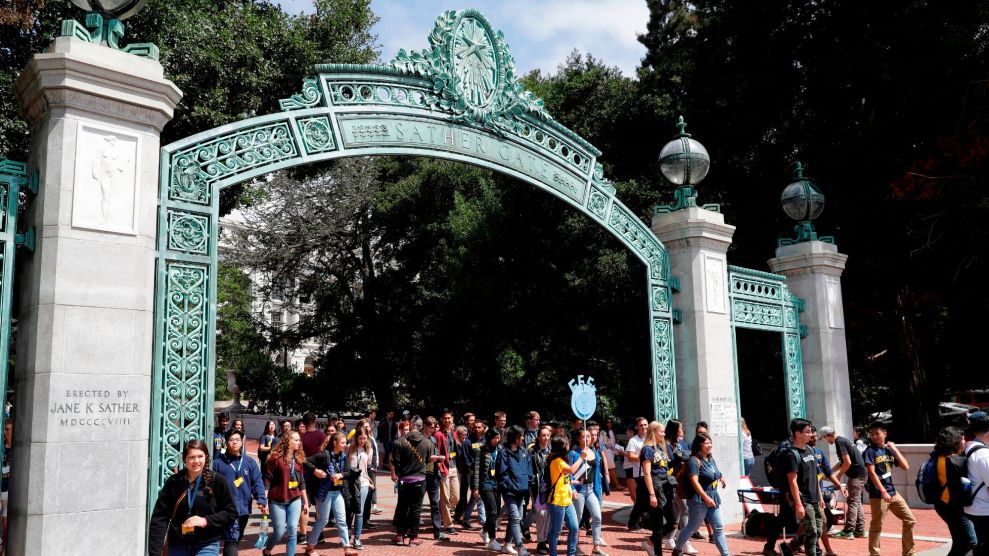

Students walk on the UC Berkeley campus. Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

Hey, here’s a neat example of how housing works in progressive cities for you—and the costs of it.

In mid-February, 150,000 applicants to the University of California, Berkeley, received a letter warning them that “a recent court order” could force the university to slash its enrollment by 3,000 slots and reduce acceptances by 5,000, sending students and their parents throughout the country into a panic.

“We want to assure you that we are pursuing every possible option for avoiding what would be a dire situation for prospective students and our campus,” wrote Olufemi Ogundele, assistant vice chancellor and director of undergraduate admissions at UC Berkeley.

Ogundele’s letter was referencing an August 2021 order mandating that Berkeley cap its enrollment at 2020 levels. In February 2022, an appeals court upheld the ruling, and shortly after Berkeley announced that it planned to appeal to the state Supreme Court.

Today, however, the California Supreme Court refused to strike down the lower court’s ruling in a 4–2 decision, virtually guaranteeing that the university will have to make good on its warnings. As a result, 5,000 students who would otherwise have been admitted will receive rejection letters in the Spring.

The decision is the result of a protracted legal battle between residents of Berkeley and the university that has played out over the last few years. In a move that the Atlantic has deemed the “apotheosis” of NIMBYism, a neighborhood group called Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods filed a lawsuit challenging the university’s plan to build new housing and academic space for Berkeley faculty and graduate students. In arguments, Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods invoked the California Environmental Quality Act, a law often used by homeowners to block new housing and homeless shelters and–ironically–stymie developments that would help the state reduce its carbon footprint.

Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods claims (with some justification) that Berkeley has continued to increase the number of students without building more dorms, displacing people in the broader community and driving up rents. However, the organization is also resistant to what is widely regarded to be the best solution— namely building more places for people to live. Instead, Phil Bokovoy, the president of Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods, has advocated that Berkeley build a “satellite campus” in another town, far away from his backyard.

If the university continues to add students, he told Slate, “We’ll end up like Bangkok, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur—dense Asian cities where there’s no transportation network. Nobody’s talking about that.”