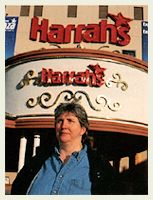

Image: Kit Miller

Darlene Jespersen never considered herself a rabble-rouser. Sure, she once ran over a neighborhood boy with her bicycle when she was a little girl (he was making fun of her training wheels). Yes, she has always been a feminist (she figures the first issue of Ms. magazine is buried somewhere in the double-wide mobile home she shares with a menagerie of stray cats and dogs on the outskirts of Reno, Nevada). But aside from her single-handed crusade to care for orphaned pets, the 45-year-old hasn’t been much of an activist.

That is, until Harrah’s casino — where she had worked as a bartender nearly all of her adult life — told her she had to wear makeup. “I don’t see why I have to paint my face to do that job when I’ve been doing it for 20 years,” says Jespersen, in a soft, quiet voice that is at odds with just about everything else about her. She is big and tall — “5 feet 9 1/2 inches,” she says proudly — with hair cropped short on top and strong hands. She projects the calm, commanding, but friendly, presence of an old-fashioned barkeep.

Jespersen has a naturally ruddy, clear complexion and has never liked makeup. When she started at Harrah’s, a company consultant recommended she try it. She did for a few weeks, then tossed the cosmetics. But last year, as part of a company-wide makeover of casinos and riverboat gambling halls around the country, Harrah’s made it mandatory for women to wear blush, powder, mascara, and lipstick at all times on the job. (Men may not wear makeup.) Both male and female employees also must undergo a makeover and be photographed at their “personal best”; supervisors periodically check to make sure staffers are living up to their photographs.

Jespersen complied with the photo requirement, but refused to put on makeup, and last summer she was let go. She contacted the Alliance for Workers’ Rights, a Reno group that had generated a lot of buzz with demonstrations against the high heels that cocktail waitresses are required to wear in many casinos. The Alliance helped Jespersen find an attorney, and she filed a federal discrimination complaint against Harrah’s in October. “Darlene is one of those people who industry has a hard time understanding,” says Alliance director Tom Stoneburner. “She won’t just go away because her life is upside down. She’ll hang in there.”

Casino executives argue that they are in the entertainment business, and employees must play their parts. But Jespersen’s attorney says the suit cuts to the core legal issue of whether women and men can be treated differently when they do the same work. Losing her job was a high price to pay to make that point, Jespersen says. “But I felt that it would have been a higher price to pay if I had stayed there and let them humiliate me.”