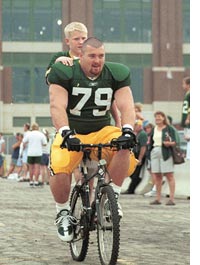

Photo: Courtesy of the Green Bay Packers

It is just after eight in the morning when Robert Ferguson (6’1″, 209 lbs.), a wide receiver for the Green Bay Packers, walks across the parking lot of Lambeau Field fully suited up and hands his helmet to 13-year-old Jason Wassenberg (5’3″, 113 lbs.), who has run up to greet him. Ferguson settles himself on the boy’s bike and hauls off to the Packers’ practice field a block away, Jason hanging on to his shoulder pads. Then Aaron Fields (6’4″, 266 lbs.) walks into the sunshine, followed by Chris Gall (6′, 247 lbs.), Ahman Green (6′, 217 lbs.), and Kabeer Gbaja-Biamila (6’4″, 255 lbs.). Each in turn is offered a bike by one of maybe 60 eager boys and girls waiting near the locker-room door of the only team in big-league sports that is owned not by a wealthy individual or group of investors, but by its fans.

The Packers belong to 110,901 people, many of them Green Bay residents who paid up to $200 each for a share in the team, and the organization makes a point of finding ways to repay the community. Each morning, when players leave for practice, they pair off with local kids. Pretty soon the parking lot is a parade of large men steering small bicycles through a haphazard aisle of a few hundred admirers, as the bikes’ owners drape themselves across the players’ backs or sprint alongside to keep up.

“It sounds hokey,” says John Dorsey, a former linebacker for the Packers who is now their director of college scouting, “but this team really cares about this community. That is the tradition, and the head coach instills that in the players. It’s the first thing you learn when you come here. The community matters.”

Donald Driver (6′, 188 lbs.), the Packers’ veteran wide receiver, zips by with eight-year-old Michael Kenyon (4’5″, 68 lbs.) leaning into his diamond-studded ear. Driver deposits Michael and his bike by the practice-field fence, signs the boy’s hat, puts something in his hands, and then picks his way to the 40-yard line, slowed by the many spectators who block his path seeking an autograph, or a handshake, or a word. Michael, meanwhile, waves his prize in the air, touchdown style. It’s Driver’s very own black mesh playing gloves, which look like they might fit Michael in, say, 2030.

“Some days, by the end of practice, I don’t have any gloves or wristbands left,” Driver says. He examines his bare arms and laughs. “But you know what? If I had kids, this is how I would want the people they looked up to to treat them.”

Welcome to Titletown, where the Packers are revered not only for bringing home more national titles than any other team in professional football, but for being…nice.

“The people who play for Green Bay are more down-to-earth than other NFL players,” says Debbie Kenyon, Michael’s mother, a dental hygienist who has come to practice in a Packers polo shirt and Packers earrings. She catches up with her son by the metal

risers the team has set up along the open, grassy practice field on Oneida Street for the thousand or so fans who come to training camp each day to watch the players go through their paces. The Packers are the only team in the league that opens all of its preseason practice sessions to the public, and the day has a casual, intimate, noncommercial feel; fans sit within a few feet of the drills while a single vendor sells ices from a handcart and someone hawks a face book of the players.

Kenyon gives her son a squeeze and points to Driver’s gloves. “I just love it that the team is not owned by some rich guy,” she says, meaning that there is no capricious Al Davis or rapacious Robert Irsay to take away the fun. Back at Kenyon’s home in Lake Mills, where the bathroom sports a Packers shower curtain and the dog is named Lambeau, there is a piece of paper that proves her point hanging in the Packers-green den, not far from the poster of Packers quarterback Brett Favre and a wall lined with Packers books. It is a single share of stock, issued in 1997, by the Green Bay Packers Inc.

Since 1923, when the Packers incorporated as a not-for-profit organization — the first article of its bylaws declaring that “this association shall be a community project, intended to promote community welfare” — the team has raised money by going directly to the people who have a share in the team’s future, the people who root for it. The most recent stock sale, in 1997, brought in $24 million and added 105,989 new owners.

For their part, the people who own the Packers appear to get nothing more for their money than a piece of paper suitable for framing — not tickets to games, which have been sold out at home for the past 18 years and, with a waiting list of 50,000 for season tickets, look to be sold out in perpetuity; not dividends; and not appreciated value, since the shares can only be sold back to the team at face value.

But appearances are deceiving, especially in a town where every other person is wearing a green Brett Favre No. 4 jersey or a gold Packers T-shirt, a town where even Bamboo, the run-down strip club, is painted Packers colors. Public ownership has conferred other, less tangible benefits, like loyalty and commitment and history, that fans who cheer for other, more flamboyant and peripatetic teams can only envy.

It’s not just the players riding kids’ bikes, or their willingness to stop and talk to fans. It’s the fact, says Pat Vance, an information- services consultant who has driven five hours from Dubuque, Iowa, to watch the team practice, that “every dollar they make on football they put back into the community and into football. No one is skimming money off the top.” It’s the fact that the Green Bay Packers Foundation, the charitable arm of the team, has given $1 million to the community, supporting such diverse local interests as aids research, an association of Hmong immigrants, and sports programs in the public schools. It’s the fact that the concession stands at Lambeau Field are run not by a private company, but by the Green Bay Curling Club and the Holy Name School and other local organizations. It’s the fact that while other teams — lured by the offer of new stadiums and guaranteed ticket sales and lucrative tax breaks — have picked up and moved in the middle of the night (think: Baltimore) or in broad daylight (think: Cleveland and Houston), the Packers have stayed put for 83 years in a city of 102,000, by far the smallest market in professional sports. It’s the fact that in Green Bay, football is still a game.

“This feels more like a hometown team than a professional team,” says Matt Gramse, dressed in a faded pair of Packers shorts, as he takes the day off from his job as a chemist to watch the team run through its drills.

“Yeah,” agrees his friend Brad Knapp, who is shaded by a Packers hat. “This is not some corporate team. They are not going to pick up and leave. You know all that money they raised? It wasn’t for a new stadium. It was to improve the old stadium. That building is going to stay right here, and so are the Packers.”

Across the street, Lambeau Field, the longest continuously occupied stadium in the NFL, stands as a red-brick monument to the enduring and happy marriage of Green Bay and the Packers. Two years ago the city, the state of Wisconsin, the fans, the NFL, and the taxpayers of Brown County all pitched in to raise nearly $300 million to make Lambeau arguably the most up-to-date facility in the NFL.

At practice this morning, as Knapp and Gramse and 1,200 other fans look on, Brett Favre throws bullet passes to Donald Driver and Robert Ferguson, while other members of the offensive team — going left, faking right — commit the choreography of the playbook to memory. The crowd is enthusiastic, clapping when a pass is completed, sending words of encouragement when it is not, and listening hard to the shouts of the coaches, which seem always to come in threes. (“Come on, come on, come on.” “Good job, good job, good job.”)

“You go anywhere in the country and you won’t find anything like these fans,” says John Tising, a retired contractor from Waukesha whose Packers stock hangs in the bedroom he shares with his wife, Carole, who may be even more of a fan than he.

“This team is owned by the people,” Carole says, explaining their devotion. “And that will never happen again.” Indeed, the NFL now requires teams to have a single majority owner, so they cannot be publicly traded and their books cannot be scrutinized. (The arrangement also makes it easier for the owners to steal teams away in the middle of the night — or put the squeeze on municipalities to pay them to stay put.) Ed Garvey, the former deputy attorney general of Wisconsin and the man who founded the football players union, says other owners are determined to make sure the Packers remain an aberration. “There will never be another Green Bay if the league has anything to do with it,” he says.

Two hours of scrimmaging, and then a horn sounds and 10 players designated in advance walk off the field to a table that’s been set up for them by the team to sign autographs. It’s mandatory — everyone takes a turn, even Brett Favre. The other players head back to the locker room. Robert Ferguson gets on Jason Wassenberg’s bike again (Jason: “Last week he took me to the pro shop and bought me a No. 89 jersey”), and fullback Najeh Davenport (6’1″, 247 lbs.) hops on Corbin Asbury’s (5’1″, 120 lbs.) bike (Corbin: “He and I and three friends went to the movies and saw Austin Powers 3”).

One by one they retreat, until there is only Aaron Fields, a free agent who is trying out for the team, and eight-year-old Greg Vance (4′, 60 lbs.) from Dubuque, Iowa, who still rides a bike with 24-inch wheels. Greg looks at Fields hopefully, and, with only the slightest hesitation, the very large man — pads and cleats and all — takes hold of the very small bike and proceeds to ride it, curled over the handlebars, standing up.

“This place reminds me of home,” Fields, an Alabaman, says as the boy chuffs alongside him — and that, exactly, is the point.