Photo: AFP Imageforum

President Bush’s enthusiasm for Social Security privatization may have had its start on a yacht off the Italian island of Elba in June 1997. As the vessel cruised the Tyrrhenian Sea, José Piñera, once the labor minister for Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet, told another passenger—a close friend of Bush’s—how he had taken Chile’s equivalent of Social Security private. Two months later, Piñera got an invitation to the Texas governor’s mansion, where he dined with Bush and Ed Crane, founder and president of the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank based in Washington, D.C. Afterward, says Crane, they retired to the library for further discussion about privatization.

Crane credits Piñera’s ardent comments that night with convincing Bush to advocate replacing part of Social Security with Wall Street investments. As he recounts it, “Bush said, ‘José, you make a very compelling case. I do believe that privatizing Social Security is the most important issue facing the nation.'” Policy analyst Peter Ferrara, who in 1981 wrote a highly influential Social Security primer for Cato while studying the Chilean system, and who has been a leading figure in the debate over the program’s future, agrees: “I believe that [conversation] was the whole genesis of the president’s commitment to personal accounts.”

Bush isn’t the only politician captivated by the suave, urbane Piñera. “He’s kind of the Pied Piper of Social Security privatization,” says Crane. Senator John Sununu (R-N.H.), author of a key Republican bill creating private accounts, introduced Piñera at a forum, declaring, “No one has done more to empower workers to save and invest for retirement than José Piñera.”

In the two decades since he left the Chilean government, Piñera has been instrumental in persuading countries across Europe and Latin America to turn public retirement systems over to the marketplace; since 1995, he has been the codirector of Cato’s Project on Social Security Choice, one of Washington’s most vigorous pro-privatization efforts. And because he is positioned as an outside expert, Piñera is expected to take on an increasingly high-profile role in helping the Bush administration and congressional Republicans campaign to privatize the program.

Trim, with abundant silver hair, gold-rimmed glasses, and perfectly knotted ties, Piñera cuts an impressive figure. He is an artful storyteller who can talk about subjects like compound interest with an almost bubbly enthusiasm. “The great thing about José is that he can speak to everyone,” says Ferrara. “He knows how to make complex ideas easy to understand.” What Piñera’s supporters generally fail to note, however, is his background as a member of one of Latin America’s most brutal regimes—and the fact that Chile’s private pension accounts have not provided the retirement security he claims.

In 1974, having just completed his Ph.D. in economics at Harvard, Piñera returned to Chile eager to help run economic policy under the new Pinochet regime. Less than a year earlier, Chile’s military—with backing from the United States—had stormed the presidential palace and seized power from the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. Pinochet would become infamous for a reign of terror that included torture, murder, and kidnappings; late last year the Chilean government announced that it will pay reparations to tens of thousands of victims, and Pinochet was indicted for murder by a Chilean court.

For Piñera, the coup was the beginning of a “revolution” that involved “a radical, comprehensive, and sustained move toward individual freedom.” In an article posted on his website titled “How Democracy Was Destroyed,” Piñera blames Allende for violating the Chilean constitution and says the coup was necessary to restore democracy. In another piece, he claims that “there was not a systematic policy of eliminating political opponents. Most of the casualties were people using violence to oppose the new government.”

Piñera had trained at Chile’s Catholic University, a campus that had close ties to the University of Chicago; hence his reputation as one of the “Chicago Boys,” a group of economists steeped in the free-market fanaticism of famed Chicago professors Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger. Harberger, a self-described admirer of Piñera, says he took note of him at Catholic University because “he was the prize student of his year.”

In 1975—after Friedman and Harberger insisted that the Chilean military impose “shock treatment” on the economy—the Chicago Boys took over major government ministries. Government spending was slashed, unemployment soared, wages were cut, production nose-dived. Many strikes were banned and wage negotiations ended. In 1978, amid growing worker unrest, Piñera was appointed labor minister. To head off a boycott campaign threatened by U.S. labor leaders, Piñera drafted a major labor law that—while touted as finally granting Chile’s repressed workers legal rights—severely restricted organizing, striking, and wage negotiating. Harberger, who is on the advisory board for Cato’s Social Security project, calls Piñera’s move “a brilliant performance” that helped convince labor leaders in the United States to call off the boycott.

With labor’s political power in check, Piñera focused on privatizing the pension system. He saw as his biggest obstacle the “tenacious belief that Social Security could and should be an effective vehicle for the redistribution of wealth.” The new system, adopted in 1981, required all new workers to sign up for private pension accounts and offered financial incentives for those in the public retirement system to switch.

The transition was expensive and funded by slashing government programs, selling off state-owned industries, selling bonds to the new pension funds, and raising taxes. Privatization costs, which also included a government subsidy for workers unable to accumulate enough in their private accounts to guarantee a minimum income in retirement, averaged more than 6 percent of Chile’s gross domestic product in the 1980s and are expected to average more than 4 percent of GDP each year until 2037.

But while the reform’s supporters argue it has been a major success story, officials both inside and outside Chile now increasingly question whether the high costs and modest investment returns have doomed Piñera’s original promise: a decent retirement income for workers at a savings for the government. Last year, the World Bank, which until recently encouraged countries to privatize pensions, published a highly skeptical report on private retirement systems in Latin America; Truman Packard, one of the report’s authors, says the bank has told the Chilean government that it must spend more to subsidize the private system and “increase its role in preventing old-age poverty.”

The bank found that exorbitant fees and other costs charged by private pension fund managers eat up as much as 15 percent of the contributions made by average Chilean workers, and even more for poorer workers. Investment returns have been far more modest than the hefty 11 percent return claimed by the private managers. The Chilean government’s pension superintendent says actual returns for someone earning Chile’s minimum wage were only 3.7 percent between 1994 and 2000.

A recent report by the Chilean government brought more grim news, forecasting that as many as half of all workers won’t be able to save enough to receive the minimum pension when they retire—even after paying into their accounts for 30 years—and will therefore rely on government subsidies. More than 17 percent of Chile’s retirees now continue working because they can’t afford to live on their pensions, according to that study, and another 7 percent want to work, but can’t find jobs.

A system that fails half of the population, says economist Dean Baker, codirector of the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research, can’t claim to have succeeded: “It hasn’t provided security to people.” Piñera himself didn’t respond to numerous requests to comment on the dismal statistics. But his economics mentor Harberger shrugs at the data. “That [Chileans] weren’t able to save enough money,” he says, “is one of those things.”

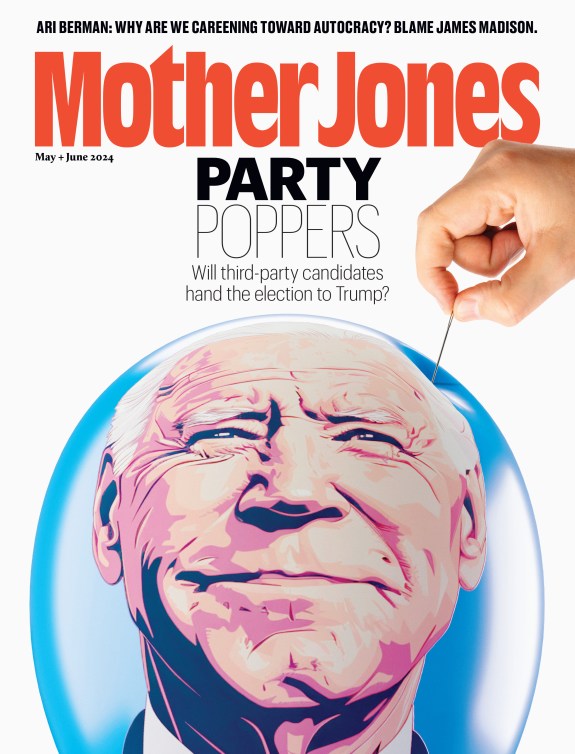

Front page image: Stacy Levere/Southcreek Global/Zuma