Photo: Kevin Irby

It’s an unremarkable November day in Houston—cloudy and cool, with thunderstorms rolling in and two men scheduled for execution at the nearby state prison in the next 48 hours. Neither of the convicts’ impending deaths has generated much press, let alone sympathy. To Dianne Clements, who has done as much as anyone to ensure that the Lone Star State’s killing chamber remains the nation’s busiest, that’s only proper.

“I don’t have any thoughts for the convicted killers—none whatsoever,” she says over a chicken salad at an Italian restaurant in an upscale Houston suburb. “Any thoughts I’d have would be for the victims’ families.”

You may not recognize Clements’ name, but chances are you’ve come across it. Whenever controversy flares over capital punishment—should we execute mentally retarded people? Juveniles? A mother who drowned her own children?—journalists from the New York Times to Fox News call to ask her opinion. And her answer, almost invariably, is yes.

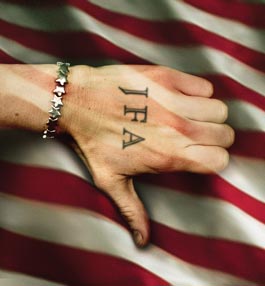

Clements, 53, is head of Justice for All, a Texas-based crime victims’ rights group. At a time when support for the death penalty is at record lows nationwide, eroded by the relentless parade of exonerated inmates, JFA and other groups like it are one of the sturdiest pillars keeping it in place.

“We need the death penalty because evil exists,” she explains. “I don’t love the death penalty—I hate it. Every execution represents an innocent person who lost their life”—the victim. But capital punishment helps deter such crimes, she says firmly. And the benefits aren’t only practical. “It’s a moral response to a horrible act. It’s retribution, which is very different from revenge.”

Barely over 5 feet and wearing pentagonal glasses, a jean jacket, and a necklace of silver balls and red beads, Clements looks more like a hip young grandma than the moralistic matron you might expect. But there’s nothing fuzzy about her opinions. She was furious last year when the Supreme Court banned capital punishment for the mentally retarded (“the whole issue is smoke and mirrors”) and for juveniles (“We’re not talking about children, we’re talking about brutal murderers with no regard for human life!”).

As for all the people freed from death row, Clements couldn’t agree more that it proves capital defendants need good legal representation. “I think they’re kind of the Antichrist,” she says of death penalty defense lawyers. “But you do want the very best representation, because…you want their convictions not to be overturned.” Even if it were ever proved that an innocent person had been executed, she says, she’d still support the death penalty.

Clements was once just another Houston soccer mom, working an office job and raising two teens—Krista and Zachary—with her husband, Woody. “It was a very typical suburban life,” she says. “Our routine was work, school, baseball.” That routine was blown apart one afternoon in August 1991. Zachary, 13 at the time, was playing with a couple of neighbors’ kids about his age, when one of the boys grabbed his stepfather’s shotgun and pulled the trigger. The blast tore a hole through Zachary’s chest, killing him on the spot.

The police called it a tragic accident, not a crime, and let the matter drop. But Clements couldn’t see it that way. “It was impossible for me to accept that my child had been killed in such a fashion and there was no response, no outrage other than my family’s,” she says. For months, she hounded the district attorney’s office, demanding action. A court finally gave the shooter a year’s probation.

That experience impelled her, and another woman who also felt the system wasn’t doing enough to punish lawbreakers, to found Justice for All. With the moral force of bereft family members and Clements’ tireless energy behind it, JFA evolved into a 4,000-member outfit. Though it remains an all-volunteer organization, it has the ear of many Texas prosecutors and politicians and has helped push through a range of laws that make life harder for criminals. State correctional officials hold the group in such respect that they renamed a prison after JFA’s other founder. Clements even got an admiring mention in George W. Bush’s autobiography, A Charge to Keep.

Ironically, JFA is an outgrowth of a movement that took root in the 1970s, when feminists began pushing for greater respect for victims of domestic abuse and rape, and harsher treatment for their attackers. A California woman whose daughter was killed in a car crash took this sort of advocacy to a new level in 1980 when she formed Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which quickly grew into a nationwide organization that played a key role in ratcheting up penalties for driving while intoxicated. Dozens of other crime victims’ advocacy groups have since sprung up all over the country.

These groups have had an enormous impact on courts, laws, and lawmakers. In many states and at the federal level, they have successfully lobbied for tougher sentences, harsher prison conditions, the registration of sex offenders, and the introduction of highly emotional “victim impact statements” in trials. California’s famously anti-death penalty Supreme Court Chief Justice Rose Bird lost her seat in the 1980s in large part thanks to the lobbying of one such group. Another group, Crime Victims United of California, helped pass the state’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” initiative and more recently was in the headlines calling for the execution of Stanley “Tookie” Williams.

But no group has focused more intently or effectively on capital punishment than JFA. Its website prodeathpenalty.com exhaustively critiques capital punishment’s opponents. JFA organized demonstrations calling for the execution of Gary Graham, a Texas convict widely thought to be innocent who was put to death in 2000, and successfully helped pressure then-governor Rick Perry to veto a bill that would have banned the execution of mentally retarded people in 2001.

None of which makes JFA’s members extremists in Houston’s Harris County, whose juries hand down more death sentences than any other county in America. The city’s mayor has donated thousands of dollars to JFA, and his victims’ services coordinator works closely with the organization, as does the district attorney’s office. “Dianne has a wonderful, wonderful heart,” says Amy Smith, director of the Harris County district attorney’s victim witness program. “She’s a good person to have on your side.”

“Executions are not something to celebrate,” Clements says. “We should just respect the fact that this difficult process is working.” Meanwhile, the two mid-November executions went off as scheduled, bringing Texas’ total to 19 for the year. For Clements, this was satisfying news.