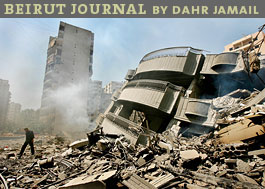

Photo: AP/Wide World Photos

Tuesday, August 1, 2006

Walking into the scene of the massacre yesterday in Qana felt like

entering a bottomless pit of despair. A black whole of sadness,

regardless of the fact that the bodies of the women, 37 young children,

the elderly, and what few men were there had been removed.

Mohammad Zatar, the 32-year-old Lebanese Red Cross volunteer I spoke

with down in Tyre, after we’d been to Qana, described the scene and the

feelings better than I can.

“I worked to rescue people after the first Qana massacre in 1996,” he told me as we stood in front of the Red Cross headquarters. “But this one was so much worse. It was the ages. So many baby kids, unlike last time. Four months to 12 years. Only six adult bodies! Only 8 injured survivors. The rest — all kids. There were no scratches on the bodies because they were all buried in the rubble. It was a bad scene.”

He told me he used to be gung-ho. That he’d always worked to

be the first on the scene, take the big risks. But yesterday he shook

his head often while we talked.

“This makes you feel so pessimistic,” he continued, “You reach a place

where you look at life like it’s nothing. I’ve cried and cried and cried, all

because of the babies. This is the worst.”

Israeli jets roared overhead in the afternoon heat, the thumps of their

distant bombs audible during the lulls of the crystal blue waves that

crashed upon the nearby beach.

“We entered the place, and we could only use our fingertips,” he said, holding up his hands to underscore his point. “Your fingers. You

had to use all your senses. When I found a tip of a finger poking up

through the rubble, I would start to shake like I was shocked by

electricity, because I knew it was another child. I’m still shocked.”

He told me of his three year-old girl. “I can’t sleep, I keep checking

her in her bed to make sure she’s still alive. I go in and just hold

her. I pick her up and hug her. Just to touch her and hold her and feel

her breathing. And now while I must keep working, every 20 minutes I’m

calling her. This has shattered me. I was never scared before, but now I

am.”

He saw me looking inside the headquarters at several of the other

volunteers as they stood around. All of them seemed to move in slow motion,

tired, lost.

“If you look in the eyes of all the rescue workers here, you see the

sadness, the badness of war,” he said, then held my eyes for a very long

time. We just stared at each other.

I gave him a firm handshake and put my left hand on his shoulder. I

wanted to give him a hug, but didn’t want to embarrass him. Instead I

told him, “Thank you for what you do. Please take care of yourself

Mohammad.”

I traveled to Qana and Tyre with my friend Urban, a Swedish-Iraqi

journalist. He and I were unable to work today. We had plans to

interview refugees in Beirut who’ve been arriving by the thousands from

the south, and just agreed after lunch to wait until tomorrow. We’re

both shattered.

My photographer friend from Holland, Raoul, also went to Tyre yesterday.

He sits downstairs at his computer. “I’m so tired, I feel like I can’t continue here so I’ll leave tomorrow,” he told me. “How do you say it, in English, when there is no more room for any more feelings?”

Yesterday’s trip was difficult, driving through so many empty villages

atop the rolling, rocky hills of southern Lebanon. Like small ghost

towns, inhabited by unattended dogs, cats, and the odd wandering herd of

goats. One blasted building, shop, house after another. We followed

small paths swept through the rubble of the streets, around the larger

chunks of concrete, to make our way through and out, then on to the next

village to repeat the process.

In Qana I spoke with two men, residents there who’d dug through the

rubble of the shelter to look for their loved ones, only to find them

dead. One of the men lost his parents. His mother was 64, his father 70.

The second man, Masen, lost his 75-year-old uncle, and his aunt, who was 70.

“They bombed it twice,” he said, “After the first bomb we heard the

screams of the women and children. And moaning. Then a minute later they

bombed it again. After that we heard no more screams. Only more bombs

around the area.”

Down at the Red Cross afterwards, I also interviewed Kassem Shaulan. He

was in an ambulance hit by an air strike. He pointed out the hole from

the rocket–an inverted flower of blooming metal, straight down the

cross-section of the cross painted in red atop the white ambulance. He

still couldn’t hear well, his vision was blurred, and he had several

scars and stitches.

“We had an old man in the back on a stretcher whose leg was blown off,”

he told me, “And a young child who is now in a coma.”

The ambulance near them was hit by an air strike as well–severely

injuring everyone in it. Kassam told me that it took them three times to

reach Qana after the shelter was bombed. “We got the call at 5 a.m. and

had to turn back because three bombs barely missed our ambulance,” he

said, “Then, the second time, we were bombed and they missed again. So that is why we weren’t able to reach there until 9 a.m. So most likely people

died because the Israelis kept us away.”

Driving home we had one of our few moments of levity of the day. A

frazzled looking young British man, covered in dust and sweat and

wearing shorts and ruffled shirt, drove up to our car on a motor scooter.

We were heading back towards Sidon from Tyre through plantations of

banana trees. “Hi,” he said. After we replied, “hello” he smiled and

continued, “Oh great–you speak English. Can you tell me, which way is it

to Tyre?”

We pointed behind us and drove on as he revved his little engine and

continued south. Urban and I looked at each other, he smiled, and I

said, “What in the hell was that?” We both laughed.

“Maybe he’s a tourist who rented his scooter in Beirut,” I suggested.

Urban replied, “He may as well ask, ‘Hey guys, can you tell me which way

the war is?'”

Most of the drive we were quiet. Just driving, and watching the

magnificent changing of colors just before sunset. The nearby hills to

the east bathed in orange. The green palm fronts seemed to glow,

thanking the sun for the light. The turquoise waters of the

Mediterranean shimmered as the afternoon breeze began to pick up.

Just driving.

And trying to take deep breaths.

Monday, July 31, 2006

Returning from traveling to Sidon on Saturday, I was emotionally

exhausted, physically sick from what I saw.

The first hospital I visited with two photographer friends was the

largest in the south, Hamoudi Hospital. After asking permission, we were

taken to several rooms of patients there.

In the first room, I met 77 year-old Mousa Sif, an old man who sat on

the end of his bed, his eyes expressing a mixture of shock, fatigue, grief and sadness. “The second day of the war the Israelis bombed my home,” he

told me.

He, his family and several neighbors had gone to the UN building nearby

their home, seeking shelter, but the UN people sent them back to their

home.

“We were bombed by the Israelis during our trip to the UN, then on our

way back home, several of the vehicles were hit,” he told me wearily,

“Then they bombed our home. There were 15 of my family in our house, and

now many of them are dead.”

In the next room I met an ambulance driver with one of his arms blown

off. Khuder Gazali, 36 years old, talked to me, his eyes fixed on mine, almost never blinking — from the shock, anger, and disbelief.

“Last Sunday people came to us and asked us to go help some people who’d

lost their legs when their home was bombed by the Israelis,” he

explained of the events that took place in a small southern village,

“We found one of them, without legs, laying in a garden, so we tried to

take him to the nearest hospital.”

On the way, an Apache helicopter rocketed his ambulance. The

rocket took off his arm before exploding behind him, critically injuring

everyone in back.

“So then another ambulance tried to reach us to rescue us, but it too

was rocketed by an Apache,” he told me while gesturing with his one arm

and explaining that everyone in that ambulance was killed, “Then it was

a third ambulance which finally managed to rescue us.”

He pointed to his shoulder, then at another patient who had ridden in his ambulance laying in nearby bed, shrapnel wounds all over his body. “This is a crime,” said Khuder, “I want people in the west to know the

Israelis do not differentiate between innocent people and fighters. They

are committing acts of evil. They are attacking civilians and they are

criminals.”

After visiting several more patients with similar stories of atrocities,

we found ourselves sitting out in front of the hospital, numb from the

experience.

“We can go to the other hospital now,” our interpreter Ayman informed

us. So we loaded into our mini-bus and drove to the Labib Medical

Center, also in Sidon.

Unlike in so many of the hospitals in Beirut, the staff at Labib was more than eager to show us their patients. They were desperate to get the information out to the world. A kind nurse, Gemma Sayer, took us around to each room.

The first person we met was a 16 year-old boy, Ibrahim Al-Hama. He lives

in a village just north of Tyre, and was swimming with 12 of his friends

in a river when they were hit by an Israeli rocket.

“Two of my friends were killed, along with a woman,” the boy told us.

In the room next door, a father talked with us whose wife and two small

children, 5 year-old Hussien Jawad and 8 year-old Zayneb, looked on. One

of Hussein’s legs was in a cast, while Zayneb had multiple injuries

to her body and butterfly stitches on the bridge of her nose.

They’d stayed in their village near the border during the first three

days of the bombing-but the bombs were getting so close they fled to

another village for eight days.

“We ran out of food, and the children were so hungry, so they left with

my wife and her sister in a car which followed a Red Crescent ambulance,

while another car took the two other sisters of my wife,” he explained

sternly, “They reached Kafra village, and an F-16 bombed the car with my

wives two sisters. They are dead. And now you see my wife and children

are injured, and we have nowhere to go.”

I could fill pages with the other cases we saw, but this is already long

enough. I didn’t sleep well last night, and still feel sick inside. I woke up

Sunday and turned on Al-Jazeera, to watch bodies being pulled from

the wreckage of a shelter in the southern city of Qana which was bombed

by Israeli warplanes.

At least 21 children and dozens of other civilians are dead. Dozens

remain buried in the rubble. So far only three survivors have been

pulled from the wreckage.

The Israeli army rejected responsibility for the deaths, and said that

Hezbollah bore the blame because it used the village for launching rockets.

The same Qana where on April 11, 1996, the Israelis bombed a shelter in

a UN peacekeeping base, killing 102 and wounding 120.

Friday, July 28, 2006

I’d been wondering why there have been fewer war planes buzzing over

Beirut the last several days. Even Dahaya, the utterly devastated southern

area of the capital, has been bombed less–while still receiving a

good pounding most afternoons, there have clearly been fewer bombs

echoing across the capital.

Israel, after claiming to have control of the small southern city of

Bint Jbail, merely a few kilometers inside Lebanon, lost at least 13

soldiers there recently. The official count of nine deaths is widely believed here to be false.

The fog of war, of course, is thick.

Bush claims he is “troubled” by the widespread destruction caused

by Israeli air strikes across Lebanon. “Troubled” while green-lighting

Israel to continue to do what it wishes. But not “troubled” enough to have his UN crony John Bolton veto a U.N. resolution condemning the slaughter of four U.N. observers in the south. While so many Americans choose to continue their sleep-walk through history, the rest of the world gets what is going on. Already the U.S. is paying a heavy political price for its unbridled support of the Israeli assault against the people of Lebanon.

The chest-beating Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert had his justice minister, Haim Ramon, tell people yesterday that everyone in southern Lebanon will be regarded as a terrorist, as their military prepared to employ “huge firepower” against Hezbollah.

“What we should do in southern Lebanon is employ huge firepower before a

ground force goes in,” quizzled Ramon at a security cabinet meeting

headed by Olmert, “Everyone in southern Lebanon is a terrorist and is

connected to Hezbollah. Our great advantage vis-a-vis Hezbollah is our

firepower, not in face-to-face combat.”

Yes–Bint Jbail has shown them this. That they will hold off on the

larger scale invasion, as it would be a disaster for Israel to face one

Bint Jbail after another. A gross analogy for Bint Jbail would be

Fallujah, April 2004. There is now a short grace period for the women,

children and elderly “terrorists” there who can’t leave. Lebanese Red

Crescent workers have told me that they can’t get there to evacuate

people, because they are too afraid more of their ambulances will be

bombed by war planes.

So it will be another “shock and awe” before rolling in the ground

troops. Read-Fallujah, November 2004.

And like Fallujah, which the U.S. military has failed to have control of

at any time following the leveling of that city, Israel will find the

same in southern Lebanon. Despite the fact that they are acting as a

Middle Eastern arm for the American Empire, and obediently labeling

anyone who resists them as a “terrorist.”

Israel’s Vietnam–their failed 18 year occupation of southern Lebanon

which ended in 2000, is fresh in their minds. Elias Hanna, a researcher

of military affairs said recently, “Israelis are traumatized by their

negative experience during the invasion of Lebanon in 1982. They are

afraid of suffering more losses in every village they try to conquer.”

And suffer those losses they will, even after dropping ton after ton of

U.S. made bombs from their U.S. supplied F-16’s on, among others, the women

and children of southern Lebanon who are unable to escape.

Clearly, the Israeli short-term memory of their Vietnam experience is

even shorter than that of the American military planners, who recently

decided to extend the tours of over 3,000 troops in Iraq.

In a televised address this Tuesday, Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of

Hezbollah, said the Israeli attack on Lebanon is an attempt by the U.S.

and Israel to “impose a new Middle East” in which Lebanon would be under

U.S. hegemony.

Most people I have discussed this with here in Lebanon get it. They

understand U.S. hegemony, after being betrayed by the Americans over and

over again. Betrayed only because it was their mistake to trust the

empire in the first place. And Lebanese understand that the Israeli

attack is an extension of that empire.

This is reflected in a poll recently released by the Beirut Center for

Research and Information. 87% of Lebanese support Hezbullah’s fight with

Israel. It isn’t suprising to me, after interviewing Christians and

Sunni Mulsims here, who in the past tended not to support Hezbollah in

any way, that most of them now thought that the Hezbollah resistance of

Israeli aggression was completely legitimate.

The poll reflected this as well, stating that 80 percent of Christians

supported Hezbollah, alog with 80 percent of the Druze and 89 percent of the Sunnis.

The same poll found that a whopping 8 percent of Lebanese feel that the U.S. supports them.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Ah, the joys of reporting on a shoe-string budget! I’ve been working the last few days with a freelance photographer from Holland, Raoul. It’s always helpful to team up—both for the companionship and to split costs. Sometimes it’s necessary, working in a war zone in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language well enough to get by on your own, to hire a driver, interpreter, and fixer. So costs add up fast, on top of the hotel, feeding, and phones, which are always necessary.

Thus, Raoul and I once again hit the streets after deciding to split the costs of a driver. Not a professional driver, mind you, but one we hired on the cheap. This means he wasn’t used to working for journalists.

He arrived late—long after the time we were supposed to meet the person we’d hoped to interview, so we jumped in the car and asked him to step on it.

Nadim, the driver, a skinny 29 year-old college grad who, like so many Lebanese, is without a regular job, slowly made his way over to the infamous Sabra refugee camp, where in 1982 Lebanese Christian militiamen massacred hundreds of innocent Palestinians.

My eyes dart back and forth between my watch and the road, as driving here always entails the obstacle course of scooters, women walking with children in tow, the odd dump truck hogging the entire road, and loads of other cars. Even though so many residents have long since fled Beirut, traffic is alive and well in many districts of the capital city.

Suddenly Nadim pulls over and opens his door. While he’s halfway out of the car he barks, “I have to eat.”

I hold my hands up and spin around to find Raoul doing the same. “What can we do?” he asks. We stare at Nadim as he waits patiently at a bread stand while I continue to glance at my watch, watching the minutes tick off.

Five ticks later Nadim is back and lowering himself back into his seat. “I was hungry,” he says, turning the ignition.

Luckily for us, the guy we’re here to interview, Ahmad, a co-founder of the NGO Popular Aid for Relief and Development (PARD), meets us with a smile near his office. We pay Nadim, coldly thank him for his time, and let him know we won’t be needing his services again. (Raoul and I agree to use a taxi service later for the return leg.)

Ahmad Halimeh

Ahmad Halimeh

Ahmad Halimeh, is one of those people who is always smiling, and always busy as hell. He brings us tea and we talk in his office. He says, “Our NGO, originally designed to serve the Palestinian refugees here in Sabra camp with health and education services, is now 90 percent engaged in working to bring relief to the war refugees from the south.”

With a staff of 20 volunteers and a few office workers, PARD is offering its medical services to over 100 families who were displaced from their homes in south Beirut and southern Lebanon. They are running a mobile clinic which is currently in the south, and also managing to find shelter for many of the families.

Our time with Ahmad highlights the dual nature of war—that it simultaneously brings out the worst in some human beings and the best in others. Ahmad and his organization are a bright spot in the darkness that has engulfed Lebanon, as the Israeli government has obtained a sort of eternal green light from the U.S. to carry on as long as it deems necessary.

“War is the total failure of the human spirit,” says British journalist Robert Fisk, which I think encapsulates it better than just about anything I have heard.

But war forces humans to survive under seemingly impossible circumstances, and in these conditions some strive to help others when barely capable of helping themselves.

We talk with Ahmad for a couple of hours and then tour the camp where so many hundreds of innocent civilians were slaughtered in 1982.

Later in the afternoon I met up with my friend Hanin, a Swedish journalist of Palestinian descent, who’d just returned from two days in Sidon, 20 miles south of here.

“The bombs are everywhere, and there are thousands of families there with nothing and nowhere to go,” she tells me. She was clearly traumatized after seeing bodies scorched by white phosphorous, and others cut to shreds by what were most likely cluster bombs.

After seeing similar atrocities in Iraq, I tell her what I knew of PTSD, and that she needs to get some sleep then start talking about what she saw.

“I spent time with a little girl who told me her brother and father were killed,” she says, beginning to cry, “And the girl asked me if my brother and father were alive. I told her, yes, they were.” She drops her head in her hands and weeps.

War is indeed the total failure of the human spirit. And unfortunately, the decrepit, despicable stench of this war is everywhere you turn in Beirut. And I wonder and wish and ask myself why people like Ahmad aren’t allowed to govern. Instead they have to pick up the pieces generated by those who do.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

“I am in Hezbollah because I care,” the fighter, who agreed to the interview on condition of anonymity, told me. “I care about my people, my country, and defending them from the Zionist aggression.” I jotted furiously in my note pad while sitting in the back seat of his car. We were parked not far from Dahaya, the district in southern Beirut which is being bombed by Israeli warplanes as we talk.

The sounds of bombs echoed off the buildings of the capital city of Lebanon yesterday afternoon. Out the window, I watched several people run into the entrance of a business center, as if that would provide them any safety.

The member of Hezbollah I was interviewing—let’s call him Ahmed—has been shot three times during previous battles against Israeli forces on the southern Lebanese border. His brother was killed in one of these battles. It’s been several years since his father was killed by an air strike in a refugee camp.

“My home now in Dahaya is pulverized, so Hezbollah gave me a place to stay while this war is happening,” he said, “When this war ends, where am I to go? What am I to do? Everything in my life is destroyed now, so I will fight them.”

That explains why earlier in the day, when driving me around, he’d stopped at an apartment to change into black clothing—a black t-shirt and black combat pants, along with black combat boots.

A tall, stocky man, Ahmed seemed always exhausted and angry.

“I didn’t have a future,” he continued while the concussions of bombs continued, “But now, Hassan Nasrallah is the leader of this country and her people. My family has lived in Lebanon for 1,500 years, and now we are all with him. He has given us belief and hope that we can push the Zionists out of Lebanon, and keep them out forever. He has given me purpose.”

“Do you think this is why so many people now, probably over two million here in Lebanon alone, follow Nasrallah?” I asked.

“Hezbollah gives you dignity, it returns your dignity to you,” he replied, “Israel has put all of the Arab so-called leaders under her foot, but Nasrallah says ‘No more.'”

He paused to wipe the sweat from his forehead. The summer heat in Beirut drips with humidity. During the afternoon, my primary impulse is to find a fan and curl up for a nap under its gracious movement of the thick air here.

Earlier he’d driven me to one of the larger hospitals in Beirut where I photographed civilian casualties. All of them were tragic cases… but one really grabbed me-that of a little 8 year-old girl, lying in a large bed. She was on her side, with a huge gash down the right side of her face and her right arm wrapped in gauze. She was hiding in the basement of her home with 12 family members when they were bombed by an Israeli fighter jet.

Her father was in a room downstairs with both of his legs blown off. Her other family members were all seriously wounded. She lay there whimpering, with tears streaming down her face.

I think I won Ahmed’s trust after that. I walked out the car, got in and sat down. He asked me where I wanted to go now.

Ahmed put his hand on my shoulder and said, “This is what I’ve been seeing for my entire life. Nothing but pain and suffering.”

A photographer from Holland who was working with me was able to respond to Ahmed that maybe we could go have a look at Dahaya.

Ahmed had told me that it was currently extremely dangerous for a journalist to try to go into Dahaya. Before, Hezbollah had run tours for people to come see the wreckage generated by Israeli air strikes. All you had to do was meet under a particular bridge at 11 a.m., and you had a guided tour from “party guys” (members of Hezbollah) into what has become a post-apocalyptic ghost town.

A couple of days ago I went there, without the “party guy” tour. A friend and I were driven in by a man we hired for the day to take us around. I was shocked at the level of destruction—in some places entire city blocks lay in rubble. At one point we came upon the touring journalists, all scurrying to their vehicles. Everyone was in a panic.

“What’s going on?,” I asked our driver. “A party guy who is a spotter said he saw Israeli jets coming,” he responded, while spinning the van around and punching the gas as we sped past the journalists lugging their cameras while running back to their drivers.

While driving we were passed by several Hezbollah fighters riding scooters. Each had his M-16 assault rifle slung across his back and wore green ammunition pouches across his chest.

Ahmed told me he’d captured two Israeli spies himself. “One of them is a Lebanese Jewish woman, and she had a ring she could talk into,” he explained as new sweat beads began to form on his forehead, “Others are posing as journalists and using this type of paint to mark buildings to be bombed.”

I doubt the ring part, and also wonder about the feasibility of paint used for targeting, but there are no doubt spies crawling all over Beirut. In Iraq, mercenaries often pose as journalists, making it even more dangerous than it already was for us to work there.

Nevertheless, war always fosters paranoia. Whom can you trust? What if they are a spy? What are their motives? Why do they want to ask me this question at this time? These types of questions become constant I my mind, and so many others in this situation where normal life is now a thing of the past. I think they are some sort of twisted survival mechanism.

We drove back near my hotel and parked again. People strolled by on the sidewalks. Ahmed said, “I will never be a slave to the United States or Israel.”