Sadly, i missed the “modesty pool jump.” I was not on hand when a gaggle of students at Ave Maria University in Naples, Florida, leapt fully clothed into their campus natatorium, so as to protest the rampant ungodliness of today’s bathing attire. I was absent, too, when Ave Maria’s Ch astity Team hosted its first-ever fashion show. I will need forevermore to satisfy myself with club founder Stephanie Smith’s tantalizing preshow promise, “It’s not going to be frumpy stuff,” for I visited Ave Maria—one of the nation’s newest, and perhaps most reactionary, Catholic universities—on a quotidian week in late autumn. The school mascot—Jax, a wrinkly English bulldog who often wears a blue blanket emblazoned “Marines”—was roistering about amid a succession of little prefab buildings, and the Ave Maria basketball squad was shambling back from the gym, looking battered. “What was the score?” I asked one player, a short, pudgy youth still in his game jersey. “One hundred twenty-six to thirty-seven,” he said between drags on his cigarette. “Pray for us. Pray for us.”

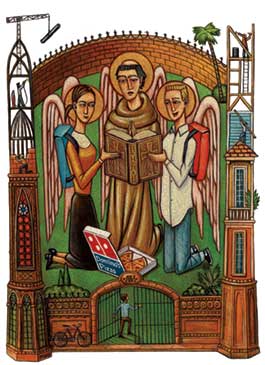

The whole scene might have been charming in its ultra-silliness were it not for the fact that the Naples campus of Ave Maria, which now boasts 400 students, is only the bud of the huge vision imagined by a billionaire Catholic hardliner. Tom Monaghan—who founded Domino’s Pizza in 1965, then sold it 33 years later, for $1 billion—has given generously to antiabortion groups and has recently made headlines with his pledge to help bankroll the long-shot presidential campaign of Sam Brownback, the Kansas Republican who is the Senate’s most fervent pro-lifer. But Monaghan, now 70, sees his principal mission and legacy as founding Catholic schools. In 2000, he opened Ave Maria School of Law near the Domino’s headquarters in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Three years later he launched the school that I visited, using a former retirement home as a temporary campus, and is spending $400 million to construct his dream—a sort of right-wing Notre Dame University designed for 6,000 students that will, this fall, become the permanent home of all Ave Maria undergrads. (The law school may relocate there, too, but not before 2009.)

Now only partially built, the future Ave Maria University sits amid a flat, swampy, and desolate expanse of tomato fields and orange groves 30 miles northeast of Naples. A brawny, 100-foot-tall, arching Gothic oratory is already rising, soon to be flanked by the nation’s largest crucifix and encircled by an entire Catholic community, Ave Maria Town, which will welcome 25,000 residents. In keeping with the tenor of Naples, where the average home costs $1.95 million and Republicans outnumber Democrats by nearly 4-to-1, the town will not be a hive of spartan monks’ cells. Rather, it will feature a mix of “affordable” $175,000 town houses, $665,000 condos, and far more palatial Corinthian-columned manses equipped with lavish swimming pools. The golf course will be “championship” caliber, and the retail core will be at once walkable and pious. “Our plan,” Monaghan told a gathering of Catholics last year (sending constitutional lawyers into a kerfuffle), “is that no adult material will appear on the town’s cable system, and the pharmacy will not sell contraceptives.”

Essentially, Monaghan plans to draw a line in the sand against a trend he deems evil. Even as the rapidly growing church lists right worldwide and a few rock-ribbed Catholic orders—most notably Opus Dei—are surging, American Catholics are becoming ever more progressive. Thirty-seven percent favor an easing of the church’s abortion policies, according to a recent cnn/USA Today/Gallup Poll, and fifty-five percent support the ordination of women. Meanwhile, several Catholic universities—among them Holy Cross and St. Scholastica—have gone so far as to play host to the dread Vagina Monologues.

Monaghan’s campaign may be a first in Catholic history. For centuries, the church’s schools have always been headed up by a religious order—the Benedictines, for instance, or the Jesuits. Monaghan, though, is stealing a page from Protestant evangelicals such as Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell and invoking a decidedly corporate structure. “I’m a businessman,” he’s pronounced. “I get to the bottom line…. And the bottom line is to help people get to heaven.”

To conservatives, Monaghan is a deep-pocketed savior. Florida governor Jeb Bush, a converted Catholic, made Ave Maria Town a special tax district like Disney World, giving the self-appointed Board of Supervisors (run by Monaghan’s development partner) wideonging powers and exempting the town from state and local laws. John DiIulio Jr., once George W. Bush’s director of faith-based initiatives, is on the university’s board of regents, and Pope Benedict XVI—who has bemoaned the “dictatorship of relativism”—sees great hope in Monaghan’s school. A former student of the pope, Reverend Joseph Fessio, is the provost there, and when Fessio visited Rome recently, he reported that the pope asked, “How’s Ave Maria?”

It’s a question that few people can answer. The university insists that all interviews—with Monaghan, students, or faculty—be arranged through a PR office. When I sent in my request, noting that I’m a believing Catholic, I got the cold shoulder. “Why should I grant interviews to someone who’s going to kick the shit out of us?” publicist Rob Falls asked me. He added, “The campus is private.”

And so I trespassed in silence, mostly, until one Saturday evening when I saw a procession of students wandering the temporary campus, saying the rosary. I fell in behind them, my voice high and plaintive in prayer. And soon I was sitting in the student center, scribbling notes as four of my co-petitioners crowded around me, monitored—and then interrupted—by a lean, crew-cut young man with a lantern jaw, who rushed the table. “Whoa, whoa, whoa,” this student said, identifying himself as a resident assistant. “Is this, like, an interview? With the media? You can’t say anything to him—that’s official policy.” So we ventured off campus, to Applebee’s.

“The first time i ever kissed a guy,” a gentle, soft-spoken Ave Maria freshman named Mersadis said over her mozzarella sticks, “I thought it was disgusting. And now I don’t want another guy to kiss me before marriage.” She took a sip of her iced tea, then continued. “In high school, I found myself looking at every girl and asking, ‘Has she given up her virginity? Is she still pure?’ Here, I’ve stopped asking. I know everyone is.”

Beside me sat a stern and erudite priest-in-training, a freshman named Aaron. “Here at Ave Maria, we follow the teachings of the magisterium,” he intoned, meaning that students regard the pope’s guidance as infallible. “We have not prostituted ourselves…. Other Catholic schools—and the rest of America—have embraced modernism and the culture of death. They have given wholehearted support to the death penalty, abortion, and euthanasia. The value of the human person is now entirely relative.”

Aaron argued that the United States can only be saved from moral perdition if it, like Ave Maria, embraces the magisterium as supreme. “We don’t believe in the separation of church and state,” he said, “and this country should orient itself toward Christ. The foundation of Western civilization rests on Christendom, which means that America owes its existence to the Catholic Church.”

But Catholicism, as Aaron sees it, has been straying ever since the early 1960s, when Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council of bishops to update and humanize the church. Revising cobwebby doctrine, the council acknowledged that other denominations and religions also offered “sanctification” and “truth.” And Vatican II radically altered the standard Mass. Prayers became shorter and simpler—and, as conservatives see it, a lax, unholy relativism gnawed its way into the church’s holiest rite. Where once the priest blessed the Eucharist in Latin, with his back to the congregation, he now faces his parishioners and speaks in the local tongue. “The offertory in the new Mass,” griped Aaron’s friend, an energetic and sandy-haired youth named Mike, “is essentially a Jewish table grace.”

A student at Florida Gulf Coast University, Mike has a fiancee at Ave Maria, and every weekend, when he pays her a chaste visit, he shuttles her two hours east to Miami, so that together they can take in a rarity not even offered on the Ave Maria campus: a Tridentine Mass, which uses the Latin and ancient prayers of the pre-Vatican II service. Quoting a 19th-century theologian, Frederick Faber, Mike called the ceremony, with its wafting incense and quietude, “the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.” Mostly, though, Mike’s faith seemed dismissive in spirit. He was disdainful of “those dissenting Catholics. They’re just going to contracept themselves out of existence,” he snickered.

Aaron, meanwhile, spoke of Ave Maria with a smug, William F. Buckleyesque swagger. He called it “the bulwark of orthodoxy. And if you are devout,” he added, “the calling of celibacy is not a problem…. Christ did not marry Mary Magdalene and all that hogwash.”

Not everyone at ave maria shares Aaron’s self-certainty and resistance to change. In fact, one student tracked me down outside a dorm and in urgent, secretive tones said, “Don’t use my name, but I saw you talking to Aaron, and you should know that most people here think he has very extreme views on modernism.”

To Aaron’s chagrin, modern Masses take place often at Ave Maria, and indeed on the weekend I visited, four Franciscan friars from New York were there, barefoot and clad in simple gray robes as they treated students to a nonstop 40-hour retreat that looked very much like a pajama party love-in. The friars were strumming winsome and lyrical folk music on their guitars and getting hip in their homilies, depicting Christ as a survivalist paintball player, and unleashing rap riffs: “You gotta go with the Jesus flow / All of us gotta know.” One brother twisted low, hips swiveling, as, prayerfully, he sang, “I want to see-eee-eee you.” The students all swayed, barefoot themselves and ardent, like so many ecstatic pilgrims at a Grateful Dead concert, before a six-foot-tall, wooden, Ikea-ish structure—a “burning bush” appointed with candles.

And for a moment I thought, hopefully, that they were getting subversive and channeling a looser-limbed Catholicism, a faith not based on persnickety rule-mongering but on a generosity of spirit—the sort that historian Thomas Cahill believes suffused the Catholic Church in its early, most formative years. Cahill is a graying don of liberal Catholicism, and in his new book, Mysteries of the Middle Ages, he depicts his spiritual forebears as social revolutionaries who laid the groundwork for modern feminism by exalting women such as Hildegard of Bingen, a mystic nun. He calls the Franciscans, who commit themselves to aiding the poor, “the world’s first hippies”—and it is his version of Catholicism that sings to me. I am with St. Martin de Porres when he argues that the precept of charity trumps that of obedience. Sitting in Stella Maris Chapel, wondered if that Catholicism was somehow thriving at Ave Maria beneath Tom Monaghan’s radar.

I soon discovered that it most decidedly is not. The students are far too controlled for that to happen. They are forbidden to live off campus, unable to take any elective courses during their first two years, barred from having TVs in their rooms, and (according to the student handbook) subject to fines if they listen to “any music which is sacrilegious, obscene or violent.” One Ave Maria adjunct music professor, Lan Lam, told me, “They seem very sheltered, very polite. It’s as if they don’t know how to act up.”

The celebrants of the burning bush were, I learned, not radical lefties but rather Franciscan Friars of the Renewal—that is, affiliates of an obscure, newly minted conservative branch of the order. “I thank God for Bill Clinton,” preached a friar/priest named Father Juniper, “because he led me to pray more, by disrespecting the sanctity of human life and the sacredness of marriage.” Juniper’s spiritual brother, David, told a long, complex story about “rescuing” a pregnant woman outside an abortion clinic. The woman, he said, fled out to the sidewalk after her abortion was already in progress, and he kept talking about the pins that, he said, were protruding from the woman’s uterus. He described his rushing her to the hospital, through New York City, as a hilarious high-action chase scene. “But, sir,” he told a police officer in frantic, pinched tones, “we’ve got this girl with us who’s got sticks in her uterus!”

I left the chapel. On the walkway outside, I crossed paths with Lantern Jaw, the sober RA who’d hassled me earlier. He was looking very Secret Service now, in a crisp black suit, so I ducked away. I went to the library. The New Yorker was there on the periodical rack, along with the Weekly Standard, the American Conservative, and Human Life Review, but I leafed through Ave Maria’s campus paper, the Angelus. University president Nicholas J. Healy Jr. writes a column for each issue. In one he calls Islam “a hostile and aggressive religion,” and goes on to lament a “widespread loss of the Christian moral vision,” most evident in Europe, where “birth rates far below replacement levels have already allowed millions of Muslims from North Africa and the Middle East to…heavily influence the political agenda.”

When I stepped outside, finally, I was relieved to find four rowdy guys huddled around the blue glimmer of a cell-phone screen, their mesh shorts drooping, their baseball caps askew and backward. “This shit is fuu-ucked up,” crowed one of them. I approached, thinking that maybe at last I’d located the wild heart of Ave Maria. “So,” I said, “are there any parties on campus tonight?” “Yeah, there’s a kegger over in Dorm 32.” “Really?” I rejoiced. But of course they were simply messing with me. “Dude, we’re Catholics,” said one. “We’ve got a lot of studying to do tomorrow. We’re going to bed.”

The next morning, i set out on my bicycle toward Ave Maria Town, the future site of the university. It was a long ride from Naples—and a journey into a different economy. When I detoured into the town of Immokalee, just six miles from the new Ave Maria, the houses lining the road were decrepit and had peeling paint, and the businesses on the main drag—La Michoacana, El Paraiso Restaurant—had bars on the windows.

Immokalee is the hub of southwest Florida’s agriculture industry, and during growing season upward of 35,000 people live here. The residents are migrant laborers, most of them from Mexico, Guatemala, and Haiti, and often they’re housed miles from town, in trailers chockablock with bunk beds. One Justice Department official has called Immokalee “ground zero for modern slavery.” His agency has successfully prosecuted six cases of involuntary servitude involving Immokalee-area workers in the past decade. A local advocacy group, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, has earned the ardent support of Catholic groups such as Pax Christi. But when I visited ciw‘s offices, it was clear that their relations with Ave Maria were icy. No one there would speak on the record about Monaghan’s project.

I rode on toward Ave Maria Town, anticipating a pleasant, if cloistered, new urbanist mecca. On the development’s website, avemaria.com, it says that the community “has been designed to human scale. Street networks, distinctive character, and environmental sustainability are integral to its planning.” One future resident, construction manager Darryl Klein, who has six children, had told me earlier that he’d moved his family from South Carolina because Ave Maria represented “the ideal American community. It’ll be a place where you know your neighbors. We’ll be around like-minded people. The kids that play with my kids—they’ll go to the same church as us. And we’ll be accepted.”

I came around a curve in the road and saw the steel skeleton of the oratory rising out of nowhere, giant and irrefutable above the flat orange groves. The concrete shells of the university buildings surrounding it were gray blobs in the distance. I turned right, following a phalanx of construction rigs—at a distance because I’d been denied a tour of the town, too. Then, as I neared the security gate, I saw my moment. The guards, not hearing a motor, were looking away, so I bent low and pedaled all-out for the holy land. For roughly a quarter-mile I was in the clear. But then a security truck pulled up beside me, its yellow roof lights aglow and fluttering. “Who are you with?” said the guard, sternly. “I’m just, like, on a training ride,” I said. A few seconds later I was back on the road to Naples.

I visited the makeshift ave maria campus one more time, on a quiet Tuesday evening, when I went back to the library to leaf through a book that many regard as the manifesto for Catholic educators: The Idea of a University, written by Cardinal John Henry Newman in 1852. The church “fears no knowledge,” Newman says, “but she purifies all; she represses no element of our nature, but cultivates the whole.” Elsewhere, Newman writes, “I wish the intellect to range with the utmost freedom.”

Soon after I jotted down these words, there was a rustling behind me: Someone was stepping in through the library door, and I turned to look. Lantern Jaw. For a second, our eyes locked. And then, not two minutes later, a dapper student security guard in a black tie was stooping beside my study carrel and speaking in murmurous tones: “I’m sorry, sir, but…”

I’d read about Ave Maria’s uniformed forces earlier, in the Angelus, where the school’s director of physical plant and security, Thomas Minick, was quoted saying that, in their vigilance, his boys were “no different than the 18- and 19-year-old Marines, sailors, and Army centurions who are guarding posts all around the world for the military.” I did not have a fighting chance. And so, without protest, I let the guard escort me outside, to my bike.

Then I rode away through the dark. Ave Maria was behind me, a bright island of light in Naples’ endless archipelago of separate, gated, green-grass communities, and I thought of the students sequestered there. I imagined them all huddled together, far from the rest of the world, in fear of their God. And I did pray for them, yes. And for my church.