Photo: Jason Madara

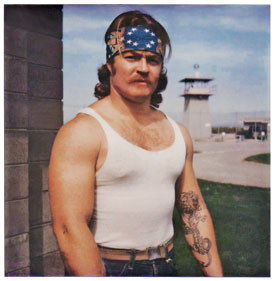

kenney trentadue was driving a 1986 Chevy pickup when he was pulled over at the Mexican border on his way home to San Diego on June 10, 1995. He was dark-haired, 5 feet 8 inches, and well muscled, a former athlete who had picked up construction work after he quit robbing banks. His left forearm bore a dragon tattoo. Highway patrol officers ran his license and found that it had been suspended, and that he was wanted for parole violations. After two months in jail in San Diego, Trentadue was shipped, on August 18, to a prison in Oklahoma City for a hearing on the parole violations. The move placed Kenney in close proximity to the most famous federal prisoner in America. In one way or another, it also sealed his fate.

Four months earlier, another car had been stopped by a state trooper, some 80 miles north of Oklahoma City. It was 10:20 a.m. on April 19, 1995, and much of the country was still waking up to the enormity of what had happened earlier that morning, when an explosives-laden Ryder truck gutted the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. The driver of the 1977 Mercury Marquis was arrested for carrying a concealed weapon and driving without tags. He gave his name as Timothy McVeigh. Two days later McVeigh was identified as the John Doe No. 1 wanted in the bombing, and fellow antigovernment extremist Terry Nichols turned himself in to police. They were indicted on August 10, and federal authorities said they had their men. But there were many who didn’t buy the tidy closure.

A sprawling Great Plains town known for its tornadoes, Oklahoma City was already the center of a swirl of theories about the crime, all of them insisting that the two men could not have acted alone. Some refused to give up on the idea of Middle Eastern terrorists, speculating about a plot headed by Saddam Hussein; others suspected an inside job by the feds. Some simply stuck to the far more plausible conviction that there were coconspirators not yet apprehended. After all, immediately following the bombing, law enforcement had been searching furiously for a man whom numerous sources said they saw with McVeigh, and who by some accounts was seen walking away from the Ryder truck—the character whose police composite sketch became known around the world as John Doe No. 2. According to the police description, this man was about 5 feet 9, muscular, and dark-haired. By some accounts, he drove an older model pickup truck and had a dragon tattooed on his left forearm.

Kenney’s brother, Jesse Trentadue, knew nothing about the resemblance between his brother and the nation’s most wanted man. But he now believes it sparked the events that would launch him on a 12-year investigation of a prison mystery and a massive government stonewalling effort. In the process, he would discover documents showing that even as the Justice Department was working to convict what it insisted were only two conspirators, its agents were actively investigating a wider plot—a plot whose possible ramifications they concealed from defense lawyers and from a public that, at a delicate moment in an election year, they were anxious to reassure. The government’s refusal to disclose what it knew—and what it did not know—may also have forestalled the nation’s best opportunity to address the problems in federal law enforcement and intelligence that would become tragically apparent on September 11, 2001.

Jesse Carl Trentadue is no liberal crusader, nor is he an antigovernment conspiracy theorist. He grew up poor in an Appalachian coal camp, called Number 7, halfway between Cucumber, West Virginia, and Horsepen, Virginia. Earlier generations of Trentadue men had all gone into the mines: One grandfather had first descended at age six, another at age 12, and both had died of black lung, as would Jesse’s father. But coal prices fell during the Korean War, and in 1961 the Trentadues followed a neighboring family to Orange County, California. They traveled, Jesse says, “like the Okies,” heading west on Route 66, sleeping beside the car at night.

Jesse’s ticket to a different life was a track and field scholarship to the University of Southern California where, like his teammate O.J. Simpson, he made all-American. After a stint in the Marines and law school at the University of Idaho, he landed in Salt Lake City, where he built a reputation as a tough, tenacious lawyer working everything from sports law to contract disputes. He met me on a warm Saturday, on a bench in front of the Judge Building, the handsome, century-old structure where he practices law. Stocky, with a graying mustache and a neat beard, a cigar between his lips, he looked like the 21st-century version of an Old West sheriff—weather-beaten, self-contained, and shrewd. His office upstairs was dominated by an enormous portrait of his brother. It depicted Kenney in a dark shirt, looking calm and earnest, bathed in a glow that evoked the portraits of saints.

As youngsters in West Virginia, Jesse says, the brothers “shared a bed and an outhouse.” Three years his junior, Kenney was a track star in high school, but dropped out after an injury and joined the Army, where he developed a heroin habit. Then he tried carpentry and factory work before discovering that he had a knack for robbing banks. “This isn’t just robbing a teller,” Jesse notes with a flush of pride. “It’s taking the whole bank down.” On Kenney’s jobs, he adds, “the weapons were empty or the firing pins had been removed. He said, ‘Robbery is one thing. Murdering is something else, and it’s not worth that.'” When Kenney got caught, “he didn’t contest it. He just went in, pled guilty, and served his time.”

Released on parole in 1988, Kenney cleaned up, started working in construction again, and got married. His first child, a boy named Vito, was born nine days after Kenney was arrested at the border.

On August 19, 1995, Kenney called Jesse’s house to report that he had just arrived at the Oklahoma City Federal Transfer Center. Jesse’s wife, Rita, an attorney and law professor, was surprised he’d been shipped from San Diego all the way to Oklahoma for a probation hearing. Kenney told her—in a conversation that was, like all inmates’ calls,”It’s that jet age stuff.”

Kenney called again that night, sounding chipper, and the brothers strategized about the parole hearing; Kenney promised to call again the next day. But no call came until early the morning of August 21, when the phone rang at Kenney and Jesse’s mother’s house. It was the prison warden. Kenney, she said, had committed suicide that night. She offered to have the body cremated at government expense—a move without precedent in federal prison policies—but Wilma Trentadue turned her down.

Five days later, Kenney’s body arrived at a mortuary in California. There were bruises all over it, clumsily disguised with heavy makeup; slashes on his throat; ligature marks; and ruptures on his scalp. Photos of the injuries were included in a letter that Jesse drew up on August 30 and hand-delivered to the Bureau of Prisons (bop), which is part of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

“I have enclosed as Exhibit ‘A’ a photograph of Kenneth’s body at the funeral,” it read. “This is how you returned my brother to us…. My brother had been so badly beaten that I personally saw several mourners leave the viewing to vomit in the parking lot! Anyone seeing my brother’s battered body with his bruised and lacerated forehead, throat cut, and blue-black knuckles would not have concluded that his death was either easy or a ‘suicide’! ” After describing Kenney’s injuries in detail, and speculating how they might have come about (bruises to his arms from being gripped, others to his legs from being knocked to the ground with batons, slashes to his throat from someone “possibly left-handed,” which Kenney was not), Jesse concluded: “Had my brother been less of a man, you[r] guards would have been able to kill him without inflicting so much injury to his body. Had that occurred, Kenney’s family would forever have been guilt-ridden… with the pain of thinking that Kenneth took his own life and that we had somehow failed him. By making the fight he did for his life, Ken has saved us that pain and God bless him for having done so!”

Two days later, on September 1, the Bureau of Prisons issued a press release stating that Kenney’s death had been “ruled a suicide by asphyxiation” and that the injuries on the body “would indicate persistent attempts…to cause himself serious injury or death.” (Officials would later put forth an elaborate scenario in which Kenney tried to hang himself but fell, bruising his head and body, and then tried to slit his throat with a toothpaste tube before succeeding in his second hanging attempt.)

In fact, as the bop would have known, no official ruling as to the manner of death had been made; rather, every communication from the state medical examiner’s office indicated it was being treated as a suspicious death. On August 22, the day after the body was delivered to the ME’s office, Chief Investigator Kevin Rowland called the local fbi office to file a complaint. On a form documenting the call, the fbi agent wrote “murder” and noted that Rowland “believes that foul play is suspect[ed] in this matter.” The state’s chief medical examiner, Fred Jordan, refused to classify the case a suicide, listing the manner of death as “unknown” pending investigation.

As was customary with suspicious deaths, within days the Bureau of Prisons formed a board of inquiry. In an unusual move, the staff attorney heading the probe was told to treat his team’s findings as “attorney work product,” which would protect it from discovery in any future lawsuit as well as from Freedom of Information Act requests. In October the bop‘s general counsel issued a memo noting that “there is a great likelihood of a lawsuit by the family of the inmate.” To this day, the bop, fbi, and Department of Justice refuse to discuss the case; spokespeople for each agency referred questions for this story to an fbi official in Oklahoma City, who declined to comment citing ongoing litigation.

Not long after Kenney died, Jesse got an anonymous phone call. “Look,” the caller said, “your brother was murdered by the fbi. There was an interrogation that went wrong…. He fit a profile.” The caller mentioned bank robbers but didn’t give many details. Jesse didn’t know what to make of the tip; he put the call out of his mind.

Exactly what happened the night Kenney died is impossible to reconstruct, in large part because a great deal of evidence went missing or was destroyed by prison officials. According to bop documents, a guard discovered Kenney hanging from a bedsheet noose in his cell at 3:02 on the morning of August 21, 1995. Stuart A. Lee, the official in charge at the prison that night, refused to unlock the cell while he waited for a video camera to film the body. According to a bop memo, he would later tell investigators that he knew Kenney was dead and he thus “was not concerned with taking any immediate emergency action.” The prison medic on several occasions said he performed cpr on Kenney, but later admitted he made no effort at resuscitation. The video of the body was never made, or it was erased, depending on whose account you believe.

Prison officials did take photos of Kenney’s body, though when the family asked for copies, they said they couldn’t find them; the photos reappeared in the fbi‘s files years later. Kenney’s clothes vanished between the time he was found hanging in his cell and the time his body was turned over to the medical examiner. Other evidence, including his bedsheets, boxers, and fingernail clippings, disappeared for several weeks; investigator Rowland would later suggest they had been in the trunk of an agent’s car. Kenney’s cell was cleaned by 2 p.m. the day of his death, before legally required examinations of the site had been made. And even though the medical examiner’s office had given orders to preserve the cell, the walls—including a pencil scrawl that prison officials called Kenney’s “suicide note”—were painted over, leaving only photos whose “lack of detail,” according to the fbi crime lab, rendered it “doubtful if this hand printing will ever be identified with hand printing of a known individual.”

Other key evidence was simply omitted from or buried in the official reports: fbi and state Bureau of Investigations officials later testified, in a lawsuit brought by the Trentadue family, that a second person’s blood had been found in Kenney’s cell, and that there were no cut marks on the noose from which he was, according to prison officials, “cut down.” According to an internal fbi memo, a prison guard told his neighbor that Kenney had been killed, and then hung in his cell as a cover-up; an inmate who reported hearing similar statements from a second guard said he was warned to keep silent and then sent to isolation. Another inmate, Alden Gillis Baker, would later give Jesse’s lawyer a note describing an incident during which, he said, Kenney got into an altercation with a guard. Eventually, he wrote, additional officers entered the cell, there was “a lot of physical violence going on,” he heard “faint moaning,” and later the sound of bedsheets being torn. (He would repeat this account in a deposition in connection with a lawsuit brought by Jesse, but a judge ruled that Baker, a convicted robber and sex offender, was not a reliable witness. In 2000, Baker was found hanging in his cell in a California federal prison.)

Government accounts of the incident relied heavily on reports from a different set of inmates. One claimed that during his two days at the prison, Kenney had seemed angry and agitated. Another claimed he was acting “upset, paranoid, and weird in general,” and thought everyone was talking about him having aids. (The Bureau of Prisons transcript of Kenney’s conversation with Jesse’s wife reads, “It’s that aids stuff,” not, as Rita insists he said, “that jet age stuff.” According to medical records, Kenney was hiv negative.) And then there were the words scrawled in pencil on the wall—”My Minds No Longer It’s Friend” and “Love Ya Familia!” Oddly, the bop investigator who took the pictures shortly after Kenney’s death wrote in a caption that the scrawl read, “Love Paul.”

The fbi agent who investigated the case immediately following Kenney’s death did not even look at the cell. He did visit the prison, but spoke only with officials, interviewing no inmates and collecting no evidence except for the photos of the cell. The case languished for months, until complaints from the medical examiner’s office reached the Department of Justice in Washington. In early 1996, the department’s Civil Rights Division took over supervising the investigation and decided that the case should be presented to a federal grand jury, which would determine whether to issue an indictment.

On July 6, 1996, more than 10 months after Kenney’s death, the grand jury was convened. Justice officials from Washington went to the trouble of commuting to Oklahoma City to oversee the proceedings. It was an election year, and President Clinton’s attorney general, Janet Reno—still under a cloud for her handling of the Waco siege three years earlier—was preparing to try McVeigh and Nichols. The last thing the doj needed was a trial, in Oklahoma City, accusing its employees of murder and obstruction of justice.

But to put the case to rest, federal officials would have to find a way around Fred Jordan, the Oklahoma chief medical examiner who had refused to classify the death a suicide. Within a few months, the local fbi office was calling Jordan—a man with a long and distinguished career, who had achieved near-heroic status in Oklahoma City for his effective and sensitive handling of the bombing victims’ remains—a “loose cannon.”

In December 1995, Jordan told an fbi official that the bureau had urged him to hold off on releasing an autopsy report until the fbi could complete its investigation. He also told the U.S. attorney’s office in Oklahoma City, according to correspondence from that office, that Kenney had been “abused and tortured”; later he would tell them, according to a bop lawyer, that “the federal Grand Jury is part of a cover-up.” In a memo to his own files, Jordan wrote that it was “very likely this man was killed.”

In search of a second opinion, doj officials asked Bill Gormley, a forensic pathologist at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, to review the case. In May 1997, Gormley called Kevin Rowland, the chief investigator in the Oklahoma medical examiner’s office, who wrote a memo to his files noting that Gormley “was troubled that [the doj] only seemed interested in him saying it might be possible these injuries were self inflicted.” In fact, Rowland wrote, Gormley had grown convinced that “this man was murdered.”

As late as July 1997, Fred Jordan told a local TV station, “I think it’s very likely [Kenney] was murdered. I’m not able to prove it….You see a body covered with blood, removed from the room as Mr. Trentadue was, soaked in blood, covered with bruises, and you try to gain access to the scene, and the government of the United States says no, you can’t…. At that point we have no crime scene, so there are still questions about the death of Kenneth Trentadue that will never be answered because of the actions of the U.S. government. Whether those actions were intentional—whether they were incompetence, I don’t know…. It was botched. Or, worse, it was planned.”

After more than a year of proceedings, in August 1997, the grand jury (which, like all such panels, had heard only evidence selected by the government) concluded its investigation without issuing any criminal indictments. The doj held back the news for two months while staff in Washington met to devise a roll-out plan that a doj aide compared to “coordinating the invasion of Normandy.” The plan targeted the media as well as Senators Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Byron Dorgan (D-N.D.), who, thanks to Jesse Trentadue’s efforts, had taken an interest in the case. In a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing a few months earlier, Hatch had quizzed then-Attorney General Janet Reno about Kenney and told her that “it looks like someone in the Bureau of Prisons, or having relations with the Bureau of Prisons, murdered the man.”

But Hatch never followed through on his stated intent to hold hearings on the case. Neither did Oklahoma Republican Senator Don Nickles, then the majority whip. In December 1997, Nickles held a press conference lambasting the feds’ handling of the case; he said prison officials in Oklahoma had told him they’d been ordered not to talk about it. The next day Nickles got a visit from Thomas Kuker, head of the fbi‘s Oklahoma City office. According to an internal fbi memo, Kuker assured the senator that he, too, had once been concerned about the case, but had become convinced that there was no foul play. After a second meeting with the fbi two months later, Nickles backed off.

The doj also continued to pressure Medical Examiner Fred Jordan, to the point where Oklahoma Assistant Attorney General Patrick Crawley wrote to a Justice Department attorney that the bop and fbi had “prevented the medical examiner from conducting a thorough and complete investigation into the death, destroyed evidence, and otherwise harassed and harangued Dr. Jordan and his staff. The absurdity of this situation is that your clients outwardly represent law enforcement or at least some arm of licit government…. It appears that your clients, and perhaps others within the Department of Justice, have been abusing the powers of their respective offices. If this is true, all Americans should be very frightened of your clients and the doj.”

Four months later, in July 1998, Jordan suddenly changed his conclusion on Kenney’s manner of death from “unknown” to “suicide,” saying he had been convinced in large part by the identification of the supposed suicide note by a handwriting expert—even though the expert had not been able to see the actual note, and had received what the doj itself considered inadequate samples of Kenney’s handwriting. Although he never fully retreated from this determination, Jordan would later say, in a deposition, that he still believed Kenney was beaten, and that he himself had been “harassed by the Department of Justice from the very beginning” of the case.

The last government investigation into the death of Kenney Trentadue, conducted by the doj‘s Office of the Inspector General (oig), was concluded in November 1999. The report was sealed, and only a brief summary made public. The full report, a copy of which was obtained by Mother Jones, ran to 372 pages and included names and many other crucial details. It also contained material taken from the secret grand jury proceeding, according to its cover page.

The oig report supported the government’s position that Kenney’s injuries had been self-inflicted. But it did find fault with the prison’s response and with the fbi‘s investigations, concluding that bop and fbi employees had lied about their actions to supervisors, investigators, and the oig itself. (In 2003, Jesse filed a complaint about what he considered shoddy investigative work in the report with the President’s Council on Efficiency and Integrity, a White House agency; the council dismissed the complaint, and when Jesse asked why, it sent him 55 pages of evidence the oig had submitted. All but 350 words had been blacked out.)

In late 2000, the civil lawsuit brought by the Trentadue family commenced in federal district court in Oklahoma City. The jury found that Stuart A. Lee, the prison official in charge the night Kenney died, had violated Kenney’s civil rights by being “deliberately indifferent to his medical needs.” Four months later, the court awarded the family $1.1 million for emotional distress (based not on Kenney’s death itself, but on the bop‘s conduct afterward). The court denounced prison employees for trying to cover up their own misconduct, declaring that, “From the time of Trentadue’s death up to and including the trial, these witnesses seemed unable to comprehend the importance of a truthful answer.” The government appealed, and the matter remains bogged down in the courts to this day.

For Jesse, the ruling was bittersweet. For more than four years, he had been investigating the case—interviewing witnesses, filing Freedom of Information Act requests, lobbying lawmakers. But he was no closer to understanding why Kenney might have been, as the medical examiner had put it, “tortured,” or why the prison and the doj would have gone to such lengths to cover up whatever occurred.

By the spring of 2003, Jesse Trentadue had all but given up on solving the mystery. Then he got a call from a small-town newspaper reporter in Oklahoma. His name was J.D. Cash, and he wanted to talk about Kenney, whose story and photo had been widely circulated on the Internet. What kind of vehicle had he been driving when he was stopped at the border? Did he have tattoos? Then Cash explained what had gotten him interested. Kenney’s particulars fit the police description of John Doe No. 2, and some photos of Kenney bore a clear resemblance to the police sketch of the alleged bomber. And both Kenney and John Doe No. 2 looked quite a bit like another man, a bank robber named Richard Lee Guthrie.

Guthrie’s name meant nothing to Jesse Trentadue, but in the far-right radical scene, he had some notoriety. In 1994 and 1995, Guthrie and his gang, the Aryan Republican Army, carried out an impressive series of 22 bank robberies across the Midwest, netting some $250,000 that they used to support the white-supremacist movement.

The ara had a flair for the dramatic. They rented getaway cars in the names of major fbi officials. At some robberies they wore Clinton and Nixon masks; at others, they tried to look like Arabs. At a December 1994 robbery they wore Santa and elf suits; the following April, they left behind an Easter basket holding a bronzed pipe bomb. In a home movie, Guthrie’s partner Peter Langan donned a black balaclava and talked about the coming white revolution. The ara‘s philosophy was old-fashioned nativism, but their style was a takeoff on the ira, with Latin American revolution and rock and roll thrown in. (Members of the Philadelphia skinhead music scene were part of the group.) Langan liked to call himself “Commander Pedro”; outside the gang, he cross-dressed and later, when sentenced to prison for the robberies, requested that a judge authorize a sex-change operation.

Cash told Jesse that some people—including some in federal law enforcement—thought the ara might have been involved in the Oklahoma City bombing, and that Guthrie could have been John Doe No. 2. (Guthrie, along with other key ara members, was finally arrested in January 1996 and was reported to be cooperating with federal prosecutors tracking the far right. That July, shortly before he was due to testify in court against Langan, Guthrie was found hanging in his cell.)

J.D. Cash, who died in May, at age 55, was an unsettling figure—a genuine crusader for truth as well as an instinctive self-promoter. A lanky man with a warm face that could turn hard in a hurry, he’d been a lawyer, mortgage banker, and entrepreneur before taking a job as the hunting and fishing reporter for the McCurtain Daily Gazette in eastern Oklahoma. Having lost friends and family in the attack, he had grown consumed with the bombing and become a central figure in the Oklahoma City “truth movement,” a loose collection of individuals and groups dedicated to identifying holes in the official story, advancing alternate theories, and gathering evidence to support them.

Cash became an acknowledged clearinghouse for information on the bombing and its endless complications, uncovering a store of vital information while putting forth some highly questionable theories. He despised the fbi and loved writing stories about the bureau’s stupidity and perfidy. His belief in a cover-up—and even government foreknowledge of the bombing—had made him a favorite among some militia types. Yet he also insisted that the bombing was part of a conspiracy by the organized far right, and wanted to see all the perpetrators brought to justice. From Cash, Jesse Trentadue would get a crash course on the questions that still lingered, years later, around the bombing.

For the federal government, a great deal was riding on public perceptions of the attack. Bill Clinton’s speech at a memorial service for the victims, and his emotional meetings with their families, drove up his popularity ratings, which had bottomed out after the 1994 midterm elections; the spotlight on violent antigovernment extremists was also credited with eroding sympathy for the antigovernment rhetoric in Newt Gingrich’s Contract With America.

But the destruction of the Murrah Building—just like, years later, the fall of the Twin Towers—also pointed to a series of deep shortcomings in federal law enforcement and intelligence. Agencies such as the fbi had plenty of agents doing first-rate crime-solving work, but their record in “domestic intelligence” was another matter. Not unlike the patriot groups obsessed with black helicopters, the fbi was consumed by conspiracy theories that reflected the fears and fantasies of its leadership. The same agency that harassed pinko screenwriters in the 1950s, bugged civil rights leaders in the 1960s, and today monitors peace activists and librarians sought to infiltrate the far right through similar means—with dubious informants and questionable surveillance. And when it did move against far-right groups, it often ended up boosting the movement it sought to thwart; the 1992 raid at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and the botched 1993 attack on the Branch Davidian compound at Waco fueled a growing fury on the far right. (The Oklahoma City bombing came on the second anniversary of the Waco disaster.)

Increasingly, that anger was targeted at the federal government and its symbols. The Murrah Building itself had been the target of a white-supremacist plot as far back as 1983. Among those involved in that failed endeavor was Richard Wayne Snell, who was later convicted of murdering a black Arkansas state trooper and a pawn-shop owner who he thought was Jewish. Snell was executed on April 19, 1995—the very day of the Murrah bombing. The final resting place of Snell’s body would be a remote religious compound called Elohim City. For those seeking evidence of a wider conspiracy in the bombing—and the federal government’s missed opportunities to crack it—all roads led to Elohim City.

the place was not much to look at—a clutch of small buildings in the Ozark Mountains in eastern Oklahoma. Elohim City’s inhabitants were followers of the late Robert Millar, who taught a doctrine known as Christian Identity, which holds that black and brown people and other “non-whites” (including Jews) are “mud people.” The community was patriarchal and polygamous, with all residents, including children, trained in the use of weapons by a visitor they called “Andy the German”—Andreas Strassmeir, a former German military officer.

For many years, Elohim City served as a sort of extremist sanctuary. Members of the Aryan Nations came through, skinhead bands made visits, young recruits showed up at the gates. Dennis Mahon, a former Klansman who had become a leader of the White Aryan Resistance, had a trailer there and participated in Andy the German’s guerrilla warfare training. In the early 1990s, the burgeoning militia movement, which helped inspire McVeigh and Nichols, became part of the mix.

Also drifting in and out of Elohim City were various informants. Internal fbi memos suggest that the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks the far right, had a source there whose tips were passed to law enforcement. (Mark Potok, the director of splc‘s intelligence project, told me that his organization had not placed an informant inside the compound, but received only second- or thirdhand reports from the compound.) Millar himself shared some information with the fbi, according to his former attorney, Kirk Lyons, in hopes of avoiding a Waco-style raid. And the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms was getting information from inside Elohim City for nearly a year before the Murrah bombing, via an ex-debutante named Carol Howe. The daughter of a wealthy Oklahoma businessman, Howe with her fiancé had formed a two-person neo-Nazi group that urged “white warriors” to take up arms against the government. In 1994 she called a racist hot line and got involved with the White Aryan Resistance and Mahon. Soon thereafter the batf, possibly wielding the threat of a weapons charge, convinced Howe to inform on Mahon, and for most of the next two years it employed her as an informant. In that capacity she made numerous trips to Elohim City.

Howe’s reports provided the batf—which, records show, shared some of the information with the fbi—with details about the weapons being stockpiled at Elohim City, Strassmeir’s combat training, and Millar’s sermons against the mud people and the U.S. government. Howe reported that Strassmeir had talked about blowing up federal buildings, and that he and Mahon had made several trips to Oklahoma City. In February 1995, Howe joined a group of Elohim City residents on such a trip; she told her batf handler that she’d stayed at the home of a former military person who demonstrated an explosive device.

Two years after the bombing, in 1997, Howe and her fiancé were indicted on charges related to their two-person “National Socialist Alliance” that included making bomb threats and possession of an illegal explosive device. She would be acquitted on all charges. There was a pretrial hearing in the case, which involved testimony from Howe’s batf handler, on the same day that Timothy McVeigh’s trial opened in Denver. At one point, the judge had the following conversation with Howe’s attorney, Clark Brewster:

The Court: Well, let me ask you this, Mr. Brewster. A lot of this makes for good conversation, like the trip to Oklahoma City, you know, before the bombing and so forth and it makes for sensationalism, and I don’t know that it really has anything to do with the Oklahoma City bombing, but I saw where you were coming from. With that McVeigh trial going on, I don’t want anything getting out of here that would compromise that trial in any way.

Brewster: What do you mean by compromise? Do you mean shared with the McVeigh lawyers?

The Court: Yes, or something that would come up—you know, we have got evidence that the [batf] took a trip with somebody that said buildings were going to be blown up in Oklahoma City before it was blown up or something of that nature, and try to connect it to McVeigh in some way or something.

Brewster did not return calls for this story; McVeigh’s lawyer, Stephen Jones, says the prosecution never gave him any information about Howe or Elohim City, but that Brewster filled him in and he attempted to have Howe testify at trial. The judge rebuffed him on this and every other attempt to show that McVeigh and Nichols hadn’t acted alone.

one day in 2004, Jesse had a kind of breakthrough—one that would put him at the center of the Oklahoma City truth movement, though it would ultimately get him no closer to proving who was to blame for Kenney’s death. A source at the fbi, who had at one point taken an interest in Kenney’s case, passed him two heavily redacted memos indicating that, more than a year after Oklahoma City, the bureau had been investigating a link between the bombers and bank robber Richard Guthrie’s ara—a connection that ran through Elohim City.

Jesse filed a Freedom of Information Act request, and then a lawsuit, for documents containing information on these connections, and the bureau—after first claiming it had none—finally produced 25 documents comprising 150 pages, many of them heavily redacted.

The documents connect two investigations under way at the bureau in 1995 and 1996, both of them linked to Elohim City via informants: OKBOMB, run out of Oklahoma City, and BOMBROB, an investigation of the bank-robbing Aryan Republican Army. One of the memos, dated August 23, 1996—some 16 months after the bombing—was sent from fbi headquarters in Washington to the BOMBROB investigation. It read, “Information has been developed that [names redacted] were at the home of [redacted] Elohim City, Oklahoma on 4/5/95 when OKBOMB subject, Timothy McVeigh, placed a telephone call to [redacted] residence. On 4/15/95, a telephone call was placed from [redacted] residence to [redacted] residence in Philadelphia division. BOMBROB subjects [redacted] left [redacted] residence on 4/16/95 en route to Pittsburgh [sic], Kansas where they joined [redacted] and Guthrie.” At that time, some ara suspects lived around Philadelphia, and Pittsburg, Kansas, was the site of an ara safe house. The document makes clear that the bureau was interested in communication between McVeigh and the ara immediately before the bombing, and that Guthrie himself was in Pittsburg—some 200 miles from Oklahoma City—three days before the attack.

In addition, the memos indicate that the fbi received reports of McVeigh calling and possibly visiting Elohim City before the bombing, at one point seeking “to recruit a second conspirator.” The documents also have one source reporting that McVeigh had a “lengthy relationship” with someone at Elohim City, and that he called that person just two days before the bombing. (These documents were never shown to McVeigh’s lawyer.) The Justice Department and the fbi would not comment on the documents; an fbi spokesman in Oklahoma City told me that the bureau is confident it has caught and convicted those responsible for the bombing.

Jesse believes that McVeigh’s contact was Strassmeir, a fixture in many Oklahoma City theories. There has been much speculation, aired most recently on the bbc show Conspiracy Files this year, that Strassmeir had ties to U.S. and German intelligence and might (along with his government contacts) have had advance knowledge of the plot. In February 2007, Jesse filed a declaration in court signed by Nichols stating, “McVeigh said that Strassmeir would provide a ‘safe house’ if necessary. McVeigh…said that Strassmeir was ‘head of security at some backwoods place in Oklahoma.'” Strassmeir left the country in early 1996; he was later questioned on the phone by the fbi.

Kirk Lyons, Strassmeir’s U.S. attorney, who has defended a number of far-right figures over the years, says the reality is far simpler; Strassmeir came to the United States to take part in Civil War reenactments, liked it here, and, hoping to find a bride, ended up at Elohim City. Lyons insists that Strassmeir was never a spy, except in the minds of conspiracy theorists. (“These silly right-wingers think I am Mossad,” he says. “I’ve given up arguing with these nutsy cuckoos.”)

Reached at his home in Berlin, Strassmeir told me that he met McVeigh once, at a gun show in 1993, but that they never spoke again. He said he had no intelligence affiliations and had no clues to the Oklahoma City attack before it happened; but there were definitely informants at Elohim City, he added, and sometimes surveillance planes flew overhead—probably, he thought, to check out the marijuana fields that “some of the rednecks” had planted. He confirmed that two ara members were part-time residents of Elohim City, but said that “nobody knew much about them.”

the oklahoma City bombing prefigured 9/11 in many ways. There were the missed clues; the federal informant who actually had contact with the conspirators; the turf-conscious agencies failing to share and act on vital information; and in general, a domestic-intelligence program incapable of translating surveillance into action. Just as they would misunderstand the nature of Al Qaeda, the fbi and other agencies never viewed the far right as a political movement with the strategic and tactical ability to deliver a major attack. Intelligence on these groups suffered from the broader inadequacies of domestic intelligence, especially in the use of untested freelance informants recruited under threat of prosecution. But with federal police forces and the Justice Department responsible for policing themselves, and the details of their work often shrouded in secrecy, the system remained unaccountable. The bombing “grew out of a definable social movement the authorities didn’t understand,” says Leonard Zeskind, a researcher who has tracked the far right for more than 30 years. “It went unsolved because of the character and gross mismanagement of the investigation. It was an outrageous crime, and the size of the crime magnifies the level of incompetence.”

In fact, after the bombing law enforcement’s failures were not corrected but rewarded. Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which severely restricted federal courts’ ability to grant habeas corpus relief, paving the way for speedier executions (like that of Timothy McVeigh), and ultimately for Guantanamo. It also restricted the rights of immigrants, extended surveillance capabilities, and provided $1 billion in authorization for antiterrorism work, half of it for the fbi. The act raised only muted protest, perhaps in part because it was signed into law by a Democratic president. Yet there can be no doubt that the roots of the Patriot Act were planted not in the chasm of Ground Zero but in the dusty soil of Oklahoma.

For Jesse Trentadue, the ara-Oklahoma City connection has suggested what he believes is the missing motive in his brother’s killing: Just as J.D. Cash posited in his first phone call, he now believes that whoever interrogated Kenney took him to be John Doe No. 2—and that Kenney died during an interrogation gone bad. He has no proof for that theory, though he continues to pursue all leads—interviewing McVeigh’s death-row neighbor, David Paul Hammer; preparing to formally depose Terry Nichols; seeking to obtain a surveillance video he believes exists of the Murrah Building area shortly before the blast. But by now, Jesse is after more than his brother’s killers. He has become an American archetype, the citizen-investigator—still propelled by the sense of justice that first drew him into the law, but no longer convinced of the government’s ability to see that justice is done.