One day in Iraq, a friend picked me up from the house in Baghdad’s Mansur district and took me to the Shaab district of east Baghdad. We drove past checkpoints manned by “Awakening” militias created by the Americans to counteract the Shiite-led Mahdi Army militia. My friend, a Shiite himself from Shaab, put a tape in the cassette player. “Now we are the Mahdi Army,” my friend laughed, as the singing started. The songs praised populist anti-American cleric Moqtada al-Sadr and the Iraqi militia loyal to him, which frequently blew up or kidnapped Americans and other foreigners. Later, Mahdi Army members asked my friend suspiciously if I was a foreigner (yes) who drank alcohol or slept with Iraqi women (no). The Mahdi Army had wanted to kidnap me, and had hoped to find the proper pretext to justify it in my immorality. Fortunately, I’m still here.

This was December, month three of my last trip to Iraq. Much has changed in the country since then, and President Obama will surely change things even more. But for even a fragile peace to hold in Baghdad, it’s important for Obama officials to understand what has not changed since Bush led the charge. On the list: the love the Shiites feel for Sadrists, the Mahdi Army, and the extensive social services they provide. Even though the Mahdi Army has gone to ground, they still exist—and await Sadr’s orders impatiently. In a fissiparous and fragile Iraq, these militias are here to stay. Let me take you on a Sadrist-guided tour.

Mustafa Mosque

The Mustafa Mosque in Ur was a Baath party office until Sadrists took it over. By 2006 the Mahdi Army had converted the mosque into a command center, launching arrests targeting radical Sunnis and former Baathists. American and Iraqi forces then raided it, (and the mosque’s Sadrist imam fled to Qom, Iran) but Abu Hassan, assistant and caretaker of the mosque, remained behind to repair it. Born in Sadr City in 1972, Hassan is a muscular and voluble man who informally leads the Ur district. He was always a Sadrist, he told me with a smile, and had followed Sadr’s father, Ayatollah Muhamad Sadiq al-Sadr, until he was killed in 1999. While repairing the mosque, Abu Hassan maintained an office in an adjacent one-room structure. There he sat on the floor behind a desk and received guests and supplicants.

Abu Hassan’s office was rarely empty. On one of my visits I found him distributing bags of clothes and rations to poor women in black abayat, many from families displaced by Sunni militias, or related to Mahdi Army martyrs. The Sadrist office gave these women such staples as milk, oil, rice, and sugar. Many still lived in tents in the nearby Shishan, or Chechen, neighborhood, thus named because Iraqis thought Chechnya was very poor. The family of an unmarried Mahdi Army martyr received 75,000 dinars a month (about $60), as did the family of an arrested man. The family of a married Mahdi Army martyr received twice as much. The Red Cross and Red Crescent helped such women as well, said Hassan, but the Iraqi government did not.

Another time I visited Abu Hassan, his office was crowded. Among those visiting him were two young men belonging to the Iraqi security forces. One was a member of the Facility Protection Service, a government militia that protected ministries and other Iraqi government offices but was notoriously loyal to sectarian Shiite militias. The other man belonged to the Iraqi National Guard. Both proudly told me they were also members of the Mahdi Army. “We want you to know that most of the Sadrists are working for the government,” said the FPS member. They listed many men who had been killed by Sunni militias. “I’ve been a soldier in the Iraqi National Guard for three years,” said his friend. “We saw that none of the political parties or movements are working for the benefit of the people except this movement. The Sadrists are devoting their time and effort to help Iraqi people. I thought the best way to help the people is by joining them.”

Several men were seated near them on the floor awaiting Abu Hassan’s arbitration services. He was to adjudicate a legal dispute over real estate. “We can’t reach the registration directorate,” they told me, because it was in Adhamiya, a Sunni stronghold. “We might get killed if we go there,” they added.

Abu Hassan’s faithful assistant was a handsome young man called Haidar. He sedulously did Abu Hassan’s bidding, and was in charge of feeding the guests and making tea for them. Haidar and his family had lived in Abu Ghraib, west of Baghdad, when in 2006 they were forced to leave. Radical Sunnis began killing the Shiite clerics in Abu Ghraib, he explained. Although the area near Abu Ghraib is now more stable because of the Awakening militia there, Haidar and his family, like other Shiites, do not feel reassured. “The Awakening were with the terrorists before, and they are the Awakening now.”

The owner of the house he and his family now lived in was that of a Sunni terrorist who had been expelled by the Sadrist movement. The Sadrists also provided Haidar’s family with rations. Haidar joined the Sadrist movement soon after the American invasion, and is a member of the Mahdi Army. “I don’t think I’m able to go back,” Haidar said of his old home.

Shurufi Mosque

The main Sadrist office for the area was in the Shaab district, in the Shurufi Mosque. Abu Hassan took me there several times over the course of my three months in Baghdad. When I first visited in December, locals complained that the Americans had just arrested four Mahdi Army men. I entered the mosque accompanied by Sheikh Safaa’s brother, another local leader who could vouch for me. Inside I met Seyid Jalil Sarkhi al-Hassani, imam for Friday prayers since 2006. He had a beard but no mustache, wore wire-framed glasses and a brown cloak. We met in a green guest room that was his study. A large painting of Moqtada al-Sadr’s father hung on the wall. As he prepared to enter the mosque for the Friday sermon he donned a white funeral shroud as Sadrists were wont to do, symbolizing their readiness for martyrdom.

Inside the mosque was colored light, green, with a green carpet on the floor. Straw mats were placed outside for the overflowing crowds. I saw a pistol partially covered by one man’s prayer carpet. Fluorescent lights and fans hung down from the ceiling. The dome of the mosque had been destroyed in 2006 by a suicide truck and was still not fully repaired. In one corner was a large women’s section surrounded by a tall curtain. Hundreds of men strolled in. Many were fit young Mahdi Army members, wearing tracksuits. As they sat to listen to the sermon, men would randomly stand up and shout a “hossa,” or war call, in hoarse voices—to which the audience would respond, “Our God prays for Muhammad and his family!” One man called for freeing the prisoners from American prisons. Another shouted, “Death to spies and the Americans!” Other hossas I heard that day: “Death is an honor for us, arrest is honor for us, resisting the Americans is honor for us!” and “Pray for Sadr, release of all the arrested people, and in a loud voice, death to the Americans and to their agents!”

As we left, several young men in the courtyard asked us to join them for lunch. My friend later told me that one of them was a famous local maker of roadside bombs, or IEDs, that targeted the Americans.

Washash

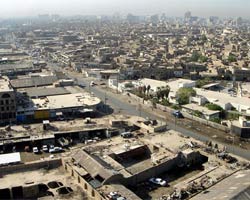

The streets of the majority Shiite Washash are unpaved dirt, many flooded with water or sewage. Electric cables hang low from rooftops and crisscross like old cobwebs. In Washash I saw more posters and banners hanging up in honor of Sadr and his father than anywhere else in Baghdad. Behind the concrete walls, only one road is left open for cars, and it is guarded by Iraqi soldiers. Elsewhere, a few narrow paths allow pedestrians to enter one at a time.

Because it was so dangerous for outsiders, my driver, whose cousin lived there, arranged for the head of the local tribal council to guide us and guarantee my safety. A Sadrist himself, Sheikh Kazim introduced me to the Mahdi Army men who surrounded us as we strolled through his neighborhood. “We are helping the people who have been displaced from other cities because of sectarianism,” he said. “Some of the help is with stipends or places to live. Also we are trying to provide gas and kerosene as much as we can.”

I met one man displaced from Dora. “They started killing [Shiites] in their houses there,” he said. “They did not get my son because he was at his college.” One month after fleeing to Washash from Dora, he said, “The Americans and the Iraqi army blew up the door to our house and they arrested us and some of our neighbors. We don’t know why.”

As Sheikh Kazim walked down the street with me, we were soon surrounded by throngs of Mahdi Army men and other residents of Washash desperate to voice their anger. One man who served in the Iraqi army’s special forces for 23 years had recently had his home raided by the Iraqi army. “They insulted me and my honor,” he shouted at me. “I spent eight years fighting in the war with Iran and a solider came to me yesterday and called me the brother of a whore!”

The men spoke of the Iraqi army unit in charge of their area much the way Sunnis spoke of the Iraqi police. “They are dealing with us in a sectarian way,” explained Kazim. “Most of the prisoners are Shiites; most of the arrests are of Shiites.”

We passed men wheeling in goods for sale on pushcarts, and at an intersection I found a tractor the Sadrists had provided as a garbage truck to clean the streets. A crowd of women in abayat sat by dozens of colorful jerricans. They were waiting for kerosene that the Mahdi Army was supposed to bring in.

I approached the women and was surprised by how eager they all were to talk to me. “My dear,” said an elderly woman with tribal tattoos on her chin, “we don’t have electricity, kerosene, or gas, and we have been insulted. To whom should we complain?”

A younger woman told me she had been expelled from the majority Sunni town of Mahmudiya after two of her sons were murdered. She was left only with her daughters now. “The terrorists killed my sons with a car bomb and the Mahdi Army are the only ones who gave me a shelter. May god bless the Mahdi Army. Anyone who says they are terrorists is lying.”

The Sadrists led me through the market that had once served the neighborhoods around Washash. We approached a narrow opening between the walls that separated Washash from Mansur. Behind it was an Iraqi army checkpoint. A soldier spotted me filming and began to approach. “He won’t dare come in,” said one of the Mahdi Army men with me, “or we will fuck him.”

The Ministry of the Interior

At the Ministry of Interior the televisions in the lobby and waiting room were tuned in to the Shiite religious channels. Shiite religious music blared from radios of police vehicles. Shiite religious banners hung on the Ministry of Interior while Shiite religious flags waved in the wind above the nearby Ministry of Oil and other government buildings. It may have seemed harmless, but it made Sunnis feel like they did not belong. It was a way of letting them know that the state now belonged to the Shiites. And more than the Shiites—there’s a close relationship between the Mahdi Army and Iraqi police in southern Baghdad. There, where the Shiite districts are dominated by Sadrists, a police officer’s phone even has a Mahdi Army song as its ring tone. The Iraqi army, known to be less sectarian, had actually come to blows with Shiite police in one local checkpoint. According to one frustrated officer from the police unit, his lieutenant colonel, called Majid, had asked him to free a Sunni prisoner and collect $4,000 from his family. The man was innocent and the court had already ordered his release. Majid in turn received a promotion. Kidnappings such as this are a key source of revenue for the Mahdi Army.

But are the American-created militias really any less problematic? Abu Hassan is suspicious of the Sunni Awakening militias. There is an Awakening group in one neighborhood, he says, now led by a man who beheaded hundreds of Shiites. “This is not logical.”

Note: Some reporting for this article first appeared on the New America Foundation website.