Is the Obama administration about to make the same mistakes in regulating Wall Street that led to the current crisis? That’s what Frank Partnoy, a professor at the University of California, San Diego and a finance expert, says in a piece in Friday’s New York Times. Partnoy would know. Back in the summer of 2008, he told Mother Jones about how the deregulation of financial markets championed by Phil Gramm, the former Senator and John McCain adviser, created a casino-like atmosphere on Wall Street. “Tens of trillions of dollars of transactions were done in the dark,” Partnoy said. “No one had a picture of where the risks were flowing…. There was more betting on the riskiest subprime mortgages than there were actual mortgages.”

The Obama administration has promised to reign in that kind of reckless, unregulated speculation. They’re off to a bad start, Partnoy warns in the Times: the White House’s plan calls for derivatives to be split into two categories. The first category, so-called “standardized instruments,” would be exchange-traded and regulated. The second category, privately negotiated “swaps,” would not be. Only a small amount of aggregate data about the swaps would be released to the public.

Why is it bad to split the “standardized” derivatives off from the swaps? Because the same idea failed before, Partnoy says. Who was responsible for turning that idea into law? Take one guess:

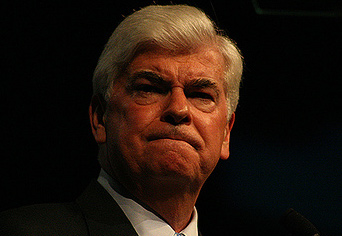

In 1989, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, a federal agency then led by Wendy Gramm, an economist and the wife of Senator Phil Gramm, a Texas Republican, issued a policy statement splitting derivatives into these same two categories. Standardized derivatives would be traded on exchanges, but individually negotiated contracts would not. Four years later, Ms. Gramm signed an order making this policy official, a sort of farewell gift to the derivatives industry before she left government service and took a place on Enron’s board.

The exception swallowed the rule, as regulators deemed more derivatives “individually negotiated.” In December 2000 Senator Gramm led a lobbying effort to cement his wife’s approach. It paid off: one of President Bill Clinton’s last official acts was to sign the law largely deregulating derivatives.

The leading derivatives lobbying group, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, is already looking to exploit the Treasury’s proposal to split derivatives markets in two. As part of its lobbying campaign to protect negotiated instruments, it insists that last year “the derivatives business — and in particular the credit default swaps business — functioned very effectively during extremely difficult market conditions.”

Congress should not be fooled by such talk again. The current crisis is proof that although most people do not trade derivatives, everyone is subject to their risks. All derivatives, exchange-traded or private, must be in the sunlight. If institutions want to negotiate individual derivatives contracts, they should tell investors the full details of their exposure.

For decades, the American financial markets attracted capital because investors believed they were getting the information they needed. That faith has been shaken. To restore it, Congress should enact all of Mr. Geithner’s proposals, except one: it should not permit any private derivatives to grow in the dark. Otherwise, today’s exception will become tomorrow’s rule.

The worry that Obama might repeat one of Phil Gramm’s biggest mistakes isn’t that far-fetched. The new president’s nominee to head the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which would derivatives, is a man named Gary Gensler. Along with top Obama adviser Lawrence Summers, Gensler was a top cheerleader for non-regulation of derivative trading in the 1990s. Will history repeat itself?