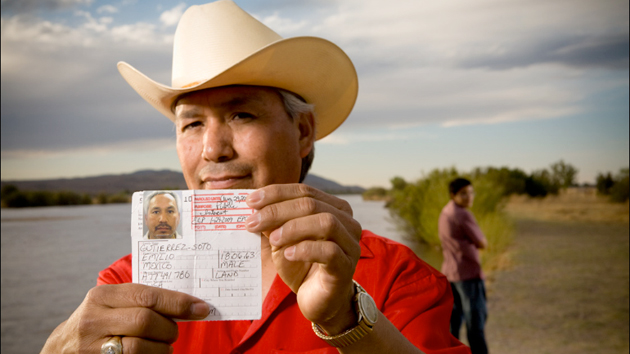

Photo: William T. Vollmann

IT WAS THE GREAT LUPE VÁSQUEZ who first informed me of the existence of the baladas prohibidas. We were at the 13 Negro drinking early in the evening, which is to say that it was not yet midnight and Lupe had not yet blacked out. The jukebox exploded into another happy song, indistinguishable to my ignorance from the others, and the grim field workers at other tables nearly smiled, while the dancing couples on the metal floor grew livelier, and several men shouted along with the singer. Even Lupe, who trudged bitterly through life, cheered up when he heard this corrido, which was naturally so loud that he had to shout into my ear for me to apprehend that it dealt with the demure lady friend of a wanted drug lord who happened to be absent when two federales visited their residence, promising her that they wouldn’t hurt him, so she told them to sit down and wait if so it pleased them; but while fixing refreshments she overheard their plan to liquidate her lover, so she sweetly invited them to rest just a moment longer, then strode out and blew them away!

Lupe’s hatred of authority exceeded even mine, and for good reason; most days he had to deal with the lordly ways of United States immigration inspectors, of foremen who might or might not offer him a job and who if they did cared about their production quotas, not about his back; of companies who didn’t pay him for the hours he had to sit in buses waiting for the frost to melt off the broccoli; and whenever he got a vacation from these entities, he got to visit the know-it-alls at the employment office in Calexico. Now and then he had also enjoyed the hospitality of Northside’s police and judges. That was why a few beers at the 13 Negro soothed the pain of the 13 Negro’s prices, and when a certain sort of corrido came on the jukebox, Lupe even smiled.

He always had stories about drugs. Once he said: Last year the asparagus crew found a lot of weed that somebody left. At first they were scared to get it, in case someone was watching, but they did it; they got it and said fuck it! And they took the marijuana. One guy sold his share for $400.

To Lupe this outcome represented not only a significant score (he was always hoping to strike it rich), but also, and I think more fundamentally in his mind, a victory over the official bullies who imprison people for drug possession.

And so that happy ballad about one loving lady’s murder of two federales was ambrosia to Lupe. I asked him how many of those songs there were, and he said: Many. They’re called the baladas prohibidas. Some also call them the narcocorridos. Of course, the more they try to stamp them out, the more popular they get. Those assholes who try to control us, we just make fun of them.

IT’S BEEN THREE YEARS that we haven’t played any narcocorridos, said Alfonso Rodríguez Ibarra, the programador at Radiorama Mexicali. Three years ago the people who owned the station and all of their affiliates decided to stop. But a year ago, the government of Baja California made it a policy not to play them.

In your opinion is that a good thing or a bad thing?

A good thing just from the marketing standpoint, he said. If we played narcocorridos, there are enough people who would be offended that we would lose the advertising.

THE POLICEMAN Carlos Pérez said that some of the most famous ballads were about Jesús Malverde, whom he called the patron saint of the narcotraffickers. He lived in Sinaloa. He was Robin Hood. He sold drugs and used the money to help the people. He was killed in a gun battle because he didn’t want to give himself up. Some say he was never caught. Some say he died of old age, and others say that he is still alive. Everybody has his own story. (One Arizona lawman proposed that discovering a Malverde image in a suspect’s wallet “might be sufficient grounds for indictment.”) I asked him whether he knew any local narco-ballads, and he replied: Most of the bad guys are Sinaloan. Here in Mexicali, there’s just middle management.

His colleague, Juan Carlos Martínez Caro, explained the genesis of the ballads thus: So the people who were dealing drugs paid singers to write songs about them. It began in the ’60s. It’s a way to make themselves look good.

I cannot say that I was greatly surprised to learn that Officer Caro preferred those corridos praising the police who captured and killed drug traffickers, such as “Comandante Reynoso.” What a good thing just from the marketing standpoint!

Just then there came an ex-policeman of eagerly jaunty sadness, bearing roses and dinner for his policewoman wife, who accepted his offerings without enthusiasm. His name was Francisco Cedeño, and he was now Christ’s age. He invited me home, where behind a wall of plywood lurked a one-room palace, anonymously male and disarrayed.

He had enlisted in the military in his early teens. A small table was strewn with photographs of his various adventures in uniform. He showed me a photo of a hectare of marijuana in Sinaloa. And here was a photo of an amapola drug flower. Here he was in the Army at 16 (it was an important stage of my life, he said wistfully), and here in police uniform at an official reception…

My wife was annoyed most of the time I was involved with the government, he said. So one day she told me I had to do everything possible to have a child or she would leave me. So I decided to find out which drug would help me perform sexually. It was crack. I lost my job due to my drug problem.

I nodded in silence.

There is no organized crime without protection in government. Here you can find yourself in trouble without wanting to. By the way, this Mafia is run by families. But a person like me, well, I grew up on a ranch; I didn’t know anyone. But if I have a brother who’s a drug dealer and I’m in the military, I’m not gonna catch my brother. If my brother harvests marijuana, I’m gonna protect him. But to do that I have to share money with my bosses.

First you harvest it, and he showed me another photo. The owner of this field is a politician. It’s not easy when you walk with God, but then no one harms you. The next photograph depicted soldiers destroying a field. But behind this field, said Francisco Cedeño with what I was already calling the narcocorrido smile, there are five more, even bigger! We just took our orders; we were supposed to destroy one and leave five, because if you didn’t follow orders you didn’t live to tell about it.

I heard narcocorridos in the military. Everyone enjoyed them. There are people worthy of respect in the military and the police who don’t do drugs. But everyone listens. I composed one for my wife, he said, and here I thought again of that weary, bitter, slender policewoman to whom he brought dinner and roses, and with whom he claimed to read the Bible every day.

Now he began to search everywhere for the corrido he had written in honor of his wife, but he couldn’t find it, so, changing his clothes and donning a hat to formalize the performance, he sang what snatches he remembered:

In Baja California / there are very valiant women.

Don’t take my word for it; / all the people say it!

This corrido is for them; / I’m always thinking of them.

There is one I carry in my chest, / or my soul it could be called.

Even for many huevos / I wouldn’t want to trade her.

The way she carries herself / makes the people respect her.

She’s a norteña, / this valiant woman.

Some call them patrona / because they give us food.

Some love drug dealers; / some love the law!

That was as much as he could remember.

ANGÉLICA, WHO WAS loitering on the street but had an urgent all-night appointment working at a restaurant whose name she couldn’t remember, gladly sang a snatch of narcocorrido right there and asked which ones I preferred, the ones where they cut people up or what? The next morning she staggered upstairs to my hotel room, reeking of urine old and new, bearing a garbage bag of empty cans in each hand.

The ones I like the most are the prettier ones, like the traditional ones, she said. It used to be that the corridos sang about famous men who were brave or who were real womanizers. Now they are about men who sell drugs and kill federales, and make them larger than life. It’s almost always the same story: I sell them, I do them, I kill them. There are also some who talk about working your way to the top. You start out helping and then you’re the one who’s telling the people what to do. I don’t really like that. I kill, I do, I sell, I make fun of. The federales tell us what to do and we do it, but the drug dealers are always the big boss and nothing ever happens to them. In all the songs, they never kill the drug dealers.

Why do you think they are so popular?

People like to listen to them when they’re drunk in a cantina.

And why do drunks like to listen to them?

For people who sell drugs, it makes them feel valiant.

That was the operating word, I thought. The ex-policeman had used it in the corrido that flattered his wife.

And what about those who don’t sell drugs?

Because they play them a lot on the radio.

That begged the question, I thought. For me, the answer was this: Mexicans didn’t like being told what to do.

IT’S ALMOST ALWAYS the same lyrics. It’s a story that never ends. Angélica was referring to the narcocorridos, but her words applied equally well to the idiotic War on Drugs itself. To quote from Los Tigres Del Norte’s “Jefe de Jefes”:

I navigate under the water.

I also know how to fly in the sky.

Some say the government watches me;

others say that’s a lie.

From up high I entertain myself.

I like them to be confused.

Just as Jesus spoke in parables, likewise the narco-saints—and their listeners. The more desperate they were, the more profoundly the narcocorridos sang to them.

The hotel clerk, whom I had known for years, disliked them actively; the barber who always remembered me and said God bless you felt the same. The police expressed various tolerations, exasperations, and likings from within their collective prison of stolidity. Emily, a waitress at the 13 Negro, liked tunes more than words; narcocorridos pleased her on that basis; certainly the so-called drug culture was more normal for her than for many Northsiders; in fact I knew nobody in Mexicali who lived in isolation from it. The great Lupe Vásquez stood loyally for them; the field workers at the 13 Negro shouted the words out.

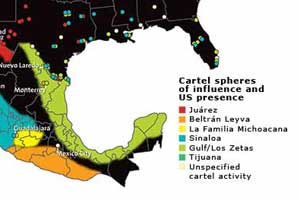

I’ve failed to mention the Tucanes de Tijuana, a famous band who composed the first narcocorridos Angélica ever heard; I’ve failed to introduce you to the most famous narcotraffickers, whom even the police speak of with respect: Chapo Guzmán and the brothers Arellano Félix from Tijuana; Cárdenas the chief of chiefs, the Valencia brothers…But maybe I have showed you that certain individuals of a daringly decorative bent can paint the walls of hell with words as yellow, hot, and sulphurous as Mexicali at three in the morning.