doug mcneall

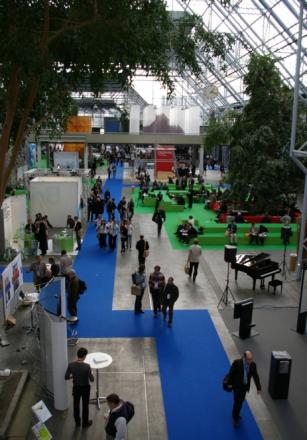

Just past the security gates and the main entrance to the Bella Center, the site of the Copenhagen climate change conference, attendees must pass through a forest of exhibition booths—there are ones set up by conservation groups, research centers, and clean business associations, all promoting their work.

What you don’t see there are displays for the fossil-fuel industries that have massive financial stakes in the negotiations here. There is no table for Exxon Mobil, which made more profits than any company in the world last year. There is no table for the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE), or any other coal group for that matter.

It’s not hard to understand why—dirty energy groups might get chased out by the armies of young activists in blue TckTckTck t-shirts.

Another reason: oil and coal companies don’t need to make their pitches here. Their work has already been done, in a sense, in Washington and other seats of government. National capitals tend to provide better access to decision-makers than international conferences such as COP15 do, according to several energy industry officials. It’s easier to work on familiar turf.

“Congress is a fantastic investment for the fossil-fuel industry,” said Steve Kretzmann, who started Oil Change International four years ago to shed light on the political influence of the oil industry.

One way to look at all of the green activism, rallies, and side events in Copenhagen is to call it a big game of catch-up, chasing after the larger fossil fuel lobbies. The U.S. oil and gas industry spent $35 million in political contributions last year; the coal mining industry spent $3.4 million; and electric utilities spent $20 million, according to opensecrets.org. So the green theater here will be eye-catching, and loud, and will try to make up for the fact that polluting industries have historically kicked their butts in getting lawmakers and bureaucrats to protect their interests.

Next week the Carbon Capture and Storage Association—a “clean coal” group—and the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association will set up in the exhibit hall. But environmental and science groups will still vastly outnumber them.

This isn’t to say more fossil-fuel representatives aren’t here—they’re just not especially visible. I haven’t yet met Brian Flannery, the infamous climate adviser for Exxon and the subject of a mock “wanted” poster at a previous climate conference, but I’m told he’s around. Such advocates attend under the odd moniker BINGOs—Business and Industry Non-Governmental Organizations. They hold private meetings each morning and are loosely coordinated by the Paris-based International Chamber of Commerce.

The cliché is that the real work for lobbyists here is “wining and dining” delegates, trying to bend their ears to the interests of particular industries. One gas-industry BINGO who didn’t want to be named told me that he and a colleague planned to identify two delegates each day who would be useful to get to know, then invite them to dinner that night. “Lobbying isn’t good for the waistline,” he said.

I asked him who exactly he’d be pursuing—which delegates, from which countries?

“Wouldn’t you like to know,” was all he offered.

This story was reported for Grist as part of the Copenhagen News Collaborative, a cooperative project of several independent news organizations. Check out the constantly updated feed here. Mother Jones’ comprehensive Copenhagen coverage is here, and our special climate change package is here.