Getting there: The bridge in Selma (Photo: Tim Murphy).Burnt Corn, Alabama—The irony of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma is that it’s the rare bridge, literal or metaphorical, that doesn’t deliver you to a more desirable place than the one you’ve left behind. The Brooklyn Bridge takes you to Brooklyn (or Manhattan, if that’s how you feel about things). The Golden Gate Bridge takes you to San Francisco. The Pettus Bridge, site of the 1965 Blood Sunday attack on Civil Rights marchers, takes you…nowhere.

Getting there: The bridge in Selma (Photo: Tim Murphy).Burnt Corn, Alabama—The irony of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma is that it’s the rare bridge, literal or metaphorical, that doesn’t deliver you to a more desirable place than the one you’ve left behind. The Brooklyn Bridge takes you to Brooklyn (or Manhattan, if that’s how you feel about things). The Golden Gate Bridge takes you to San Francisco. The Pettus Bridge, site of the 1965 Blood Sunday attack on Civil Rights marchers, takes you…nowhere.

What you find when you walk across is instead, and somewhat improbably, more depressing than the decaying downtown Selma you’ve left behind: There’s the National Voting Rights Museum, which you’ll probably never find, because while it relocated recently, no one’s gotten around to replacing the road signs pointing you to the old site; there’s a monument of rocks with a verse from Joshua: “When your children shall ask you in time to come saying ‘What mean these stones,’ then you shall tell them how you made it over”; and there’s the Civil Rights Memorial Park, overgrown and out of sorts, strewn with litter, broken glass, weeds, and a defined by general lack of maintenance or interest—or basically what you’d expect from a memorial built underneath a highway overpass.*

Unfinished business: Selma’s Civil Right Memorial Park, overgrown and out of sight.The passage from scripture, next to plaques honoring Hosea Williams and John Lewis, is kind of beautiful, but other than that, the greatest metaphor in recent American history is immediately followed by shuttered retail and then miles of farmland. On a Sunday afternoon, we see only two other group walking the bridge. But maybe that’s kind of the point: Crossing a bridge out of Selma really shouldn’t mean that much—it shouldn’t require three separate attempts, a National Guard escort, and heavy doses of prayer; just stick to the right, hold onto the railing, and you’ll be just fine.

Unfinished business: Selma’s Civil Right Memorial Park, overgrown and out of sight.The passage from scripture, next to plaques honoring Hosea Williams and John Lewis, is kind of beautiful, but other than that, the greatest metaphor in recent American history is immediately followed by shuttered retail and then miles of farmland. On a Sunday afternoon, we see only two other group walking the bridge. But maybe that’s kind of the point: Crossing a bridge out of Selma really shouldn’t mean that much—it shouldn’t require three separate attempts, a National Guard escort, and heavy doses of prayer; just stick to the right, hold onto the railing, and you’ll be just fine.

One other quick thought: Selma is the rare town we’ve visited that actually underplays its transformative place in American history. America produces historic landmarks and roadside attractions like Slovenia produces consonants—and there’s something nice about that: With some ingenuity, a few greased palms, and plenty of water any speck on the map can grow up to be something, be it Wall Drug, South Dakota, or, what the heck, Las Vegas. But sometimes it’s nice to come to a place like the Edmund Pettus Bridge and find it really is just a bridge.

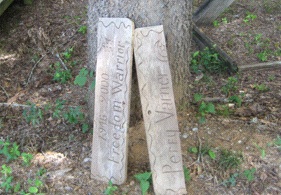

*To be a bit more detailed, the memorial consists of wooden walkways through the Spanish moss grove, with at least half a dozen single-room skeleton houses (no roofs, just frames). Some rooms, but not all, contain the names of martyred Civil Rights activisits, but at least a few names are missing. All of the signs that would normally tell you what you’re looking at are out of commission, mostly stripped of their old literature. One of the few bits of life that’s left is a display with an illustration of martyrs, marchers, and young people planting a tree, with a label that I could only partially make out: “The Civil Rights [Dream, I think] that might have been.” By design or decay, it seems appropriate.