<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MTR1.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>.

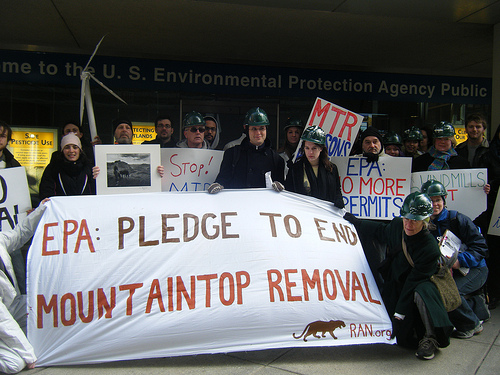

Activists from across Appalachia are in Washington, DC, this week to call attention to mountaintop removal coal mining, the controversial practice of blowing up mountains to reach coal reserves. Appalachia Rising participants will march from the Environmental Protection Agency headquarters to the White House on Monday and hold a lobby day Tuesday to call attention to the practice they say is destroying their homes and communities.

“The region’s not going to survive much longer if we don’t do something soon,” says Dustin White of Charleston, W.Va., in town for this week’s events. White, a 27-year-old with a crew cut and glasses, is orginally from James Creek, a community of about 100 people on Cook Mountain in the southwestern part of West Virginia. The mountain was named for one of his ancestors, and many are buried nearby. Two months ago, Patriot Coal Corporation, one of the largest mining companies in the country, told White’s father, a former coal miner, that they would soon be blasting near his home.

White describes nearby towns that are no longer, as residents have been bought out by coal companies or simply abandoned due to the blasting and diminished quality of life. There’s Lindytown, which sits on the other side of Cook Mountain in the valley below a Massey MTR site, which he says went from 100 people a few years ago to just three today. White fears the same might happen to his town.

“I’m in limbo—I don’t know whether my hometown is going to exist in 20 years,” said White.

“Twenty? Try five!” chimed in Mary Love, an anti-mountaintop-removal activist from Kentucky.

White says he’s not anti-mining. He just thinks it can and should be done safely underground, the way it was before mining companies had the machinery, firepower, and more lenient environmental rules that have allowed them to blast mountains and dump the waste in nearby valleys. The practice was also accelerated in the past eight years, thanks to a 2002 Bush administration change to the Clean Water Act rules that made it legal to fill valleys with waste from blast sites. The same change also made it legal to dump the debris and even waste like old toilets and junk cars into valleys.

While topless mountains serve as shocking visual evidence of environmental devastation in Appalachia, it’s the waste issue that creates real problems for communities in the region. After the tops of the mountains are blown off, the waste debris dumped in nearby valleys often blocks waterways and causes flooding. The debris includes a number of toxic heavy metals that end up in the water, causing a litany of health problems. Areas close to the blast sites have lower birth weights and higher rates of mortality, lung cancer, and chronic heart, lung, and kidney disease. A study released earlier this year found an average of 11,000 more premature deaths per 100,000 residents in the counties with the heaviest mining.

There has been some improvement in oversight on MTR under the Obama administration, but not as much as the folks rallying in DC would like to see. In June 2009, the Obama administration announced that it was ending fast-tracked reviews for MTR operation permits and would require tougher environmental review before permits are issued. The EPA later announced that it was putting pending permits through closer scrutiny, and released new guidance in April on enforcement of existing state and federal laws. But the agency has also approved new MTR permits, which hasn’t given activists much hope that things have changed enough to protect their communities.

Environmental regulators say they’re doing as much as they can to enforce existing clean water laws. But when considering MTR permit applications, they say they are hampered by the fact that the practice is still legal. “Until that changes, we have to use the tools that we have,” said Nancy Sutley, head of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, in a call with reporters last year. To that end, a bipartisan pair of senators introduced legislation that would classify mining waste as a pollutant, effectively banning companies from dumping it into valleys and waterways. Sens. Ben Cardin (D-Md.) and Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) first released the Appalachia Restoration Act in March 2009, but they’ve been tweaking the language and plan to have an updated version in the coming weeks. Advocates are still hoping they can actually get a vote on the Senate floor this year.

“I really do believe that we will see this bill move before the end of this year,” says JW Randolph, a legislative associate with Appalachian Voices. But if they don’t, the people of Appalachia will keep pushing the federal government. “This fight has always been led by people far outside the beltway, in the small mountain communities of central Appalachia, who know that they are still blowing up our mountains and there still oughta be a law to stop it.”

In an interview with Mother Jones, Cardin was cautiously optimistic that the bill could be included in a larger package, and could have bipartisan backing. “We’re looking to see if we can find a way, in this difficult political environment where we don’t have a lot of vehicles, to get it done before the end of the year,” said Cardin. “The EPA is operating under the Clean Water Act, and they have taken certain aggressive steps that have helped, but there are gaps.”

For the many activists rallying in DC this week, those gaps have personal significance.

“I want to make sure I have a home to go back to,” said White.