The mola mola, also known as the ocean sunfish, and in science as Mola mola (Latin mola: millstone), is one of my favorite creatures. There aren’t many species we informally call by their binomial names. But mola mola is catchy, and what else would you call such a strange and endearing creature?

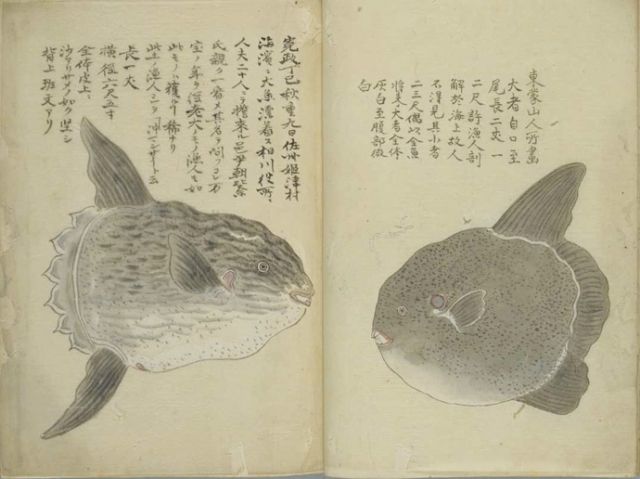

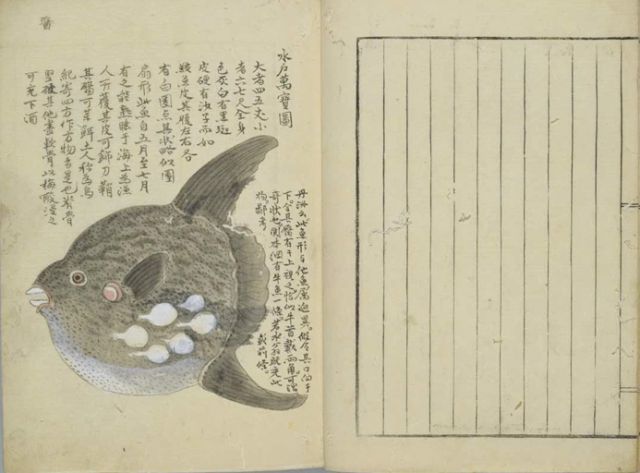

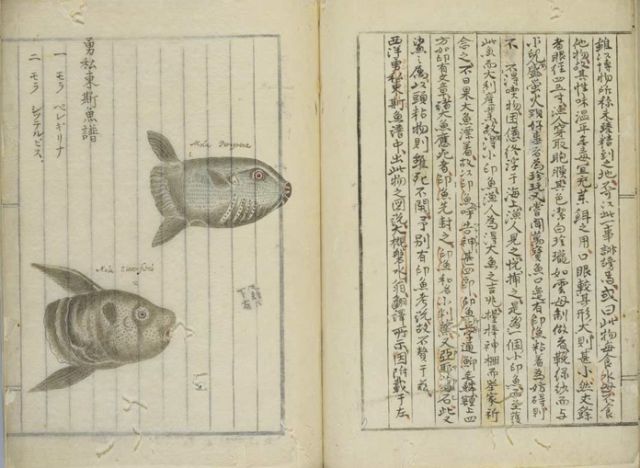

This beautiful series of paintings below all come from an old book about ocean sunfish published online at the National Diet Library of Japan. According to Pink Tentacle, the artist was Kurimoto Tanshuu (1756-1834). I’d love to know what the text says.

The last page might be views of the slender sunfish, Ranzania laevis, a close relative.

Your first thought upon seeing a mola mola might be: That is one big fish. Full grown mola molas are the largest of all the teleost (bony) fishes, averaging 2,000 pounds/1,000 kilograms, with a maximum published weight of 5,000 pounds/2,300 kilograms.

Your second thought might be: That is one insanely improbable fish. Molas truly swim their own way, synchronously flapping their dorsal and anal fins. As if you and I could propel ourselves through the water—and with surprising speed—by waving one arm and one leg.

From this skeleton, you can also see how sunfish don’t appear to have tails. The perplexing tail problem was only recently worked out by Ralf Britz at the Natural History Museum in London and G. David Johnson at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC. From the London Natural History Museum:

Britz and Johnson studied the tails of the ocean sunfish in detail by looking at the developing skeleton of larvae under a microscope. They compared its development with that of a less modified relative of the sunfish, the pufferfish. They found no sign of the caudal fin at any stage of the development of the ocean sunfish and discovered that the dorsal and anal fins grow together to form the [rudderlike] clavus.

“The colossal ocean sunfish, a pelagic fish with a wide distribution, has lost its tail fin, the main locomotory structure in all other fishes. This was a very surprising and unexpected result!” said Britz.

Here’s what it looks like all put together, as a young mola mola investigates some lucky divers off Catalina Island, California. You can also see that—when left unmolested—mola mola are naturally friendly and curious.

The mola was likely visiting the kelp beds for the services offered by señoritas—the major cleaner in the kelp beds—or some other cleaners. There’s a good living to be made eating other fishes’ parasites or debriding their wounds. More on that in a later post.

Photo by Dan Richards, NOAA, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Dan Richards, NOAA, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In the photograph above you can see a school of blacksmith, who—as they typically do when encountering señoritas—have stopped swimming and are hanging upside down, signalling their desire to be cleaned.

This beautiful mola is getting cleaned by a Moorish idol in Bali.

Credit: G. David Johnson, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Credit: G. David Johnson, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

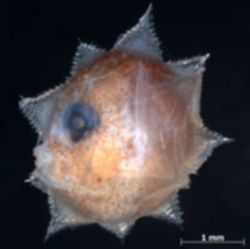

Here’s a 2.7mm-long larva of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola, from the Ichthyology Collection of the National Science Museum, Tokyo.

Here’s a larval Mola mola. Living proof that the ocean is rife with the fusion between the functional and the fantastical. [Although a friend who really knows fish pointed out that this little dude has a fairly well developed tail and tail stock. So I’m not sure where that leaves the research, above, regarding no-tail molas…]

For unwieldy swimmers, mola molas venture surprisingly deep. The video is from deep coral beds off Florida. From the YouTube page:

This ocean sunfish Mola Mola was about 5 [meters?] long and probably weighed 300-500 pounds. It was discovered during a Johnson-Sea-Link dive on a beautiful Lophelia coral reef located 40 miles east of Cape Canaveral, Florida. The white patches are where its skin has been taken off by unknown means, revealing the white cartilage beneath. Sunfish appear to have at least an ephemeral association with Lophelia coral pinnacles, as they have been seen in these locations numerous times by previous researchers. Video courtesy of Sandra Brooke, Florida Coast Deep Corals 2005, HBOI, NOAA-OER.

Some interesting research with Mola mola off southern California found they make repeated bounce dives below the thermocline (to about 150 meters /500 feet) during the daylight hours, presumably in search of their favorite gelatinous zooplankton, including salps, medusae and ctenophores. From [PDF] the paper in Marine Ecology Progress Series:

However, ocean sunfish rarely remained below the thermocline for more than a few minutes, even though surface temperatures in more northern parts of their range can be colder than the temperatures experienced during these dives. [It has been] suggested that due to physiological limitations, the magnitude and rate of change in water temperature, rather than absolute temperature, may limit vertical movements in yellowfin tuna, blue marlin and striped marlin, and the same may be true for ocean sunfish. Periodic ascents to the warm mixed layer [near the surface], therefore, may be attempts by the fish to rewarm its core body temperature (i.e. behavioral thermoregulation). Rewarming of the body could be advantageous in terms of increased mobility, digestion, assimilation and growth rates. Dive ‘recovery times’ (i.e. the post-dive period) of ocean sunfish spent in the mixed layer increased significantly as a function of maximum dive depth, further supporting this hypothesis.

The researchers only once recorded a mola mola dive below the thermocline after nightfall:

Curiously, the only instance in which a fish descended below the thermocline during the nighttime period was also the greatest depth recorded for any tracked fish. Almost 1 h after sunset, Ocean Sunfish 1 rapidly dove to 392 m (corresponding to an ambient water temperature of 6.8°C). Depth data were taken on a minute-by-minute basis during this dive period, and indicated that the fish descended at a rate of 53 m min–1, 6 times faster than typical descents observed during daytime dives (8.4 ±5.6 m min–1), and ascended at a rate of 25 m min–1. Based on the incongruous time period, swift descent rate, and the fact that other deep dives were typically associated with the initial post-handling stress, this dive could possibly represent a predator avoidance response. Ocean sunfish predators include large sharks and California sea lions Zalophus californianus, both of which are commonly found in the waters off Santa Catalina Island.

[UPDATE: David Guggenheim of 1planet1ocean and The Ocean Foundation shares the wondrous story of Sylvia Earle observing a mola mola at 1,300 feet deep during a submersible dive near Tortugas, and that it was bigger than the sub (presumably a smallish sub?). Perhaps it was fleeing a predator?]

Finally, the authors suggest another even more intriguing reason for the diurnal bounce dives. In other words, why the fish don’t just stay down deep during the day:

The vertical movements of ocean sunfish may also be limited by dissolved oxygen concentration. Four of the ocean sunfish reached depths approaching 150 m during dives. During the months of August through October, average O2 concentrations at 150 m in the study area are between 2.5 and 3.0 ml l–1, a range known to induce avoidance responses in many marine fish species. While the physiology of ocean sunfish is not well studied, oxygen concentration may also play a role in defining their habitat preferences. Therefore recovery time spent in the mixed layer by pelagic fishes may be related not only to temperature, but to recovery from hypoxia, particularly for deeper-diving fishes.

Not mentioned in the paper, but jellyfishes thrive in hypoxic waters, and are some of the only creatures to do so. Perhaps they’re trying to hide in a suffocating environment, which predators like molas—great jellyfish eaters—can only endure for short periods?

Credit: Vanessa Tuttle, NOAA/NMFS/NWFSC/FRAMD/MF

Credit: Vanessa Tuttle, NOAA/NMFS/NWFSC/FRAMD/MF

At any rate, the horizontal basking at the surface typically displayed by mola mola, as in the photo above, may be a way of warming up after deep dives while gasping for O2-rich breaths.

The paper:

- Daniel P. Cartamil, Christopher G. Lowe. Diel movement patterns of ocean sunfish Mola mola off southern California. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004. DOI: 10.3354/meps266245

Reposted from my blog Deep Blue Home.