iStockphoto

Monica Bosquez managed to “stay positive” most of the time. But in our conversation just days before she left for Ciudad Juárez, the bright and friendly program analyst for the state of Texas broke into tears. “If I don’t come back,” she said, “make sure you tell people what happened.”

For the thousands of American citizens who, like Bosquez, are married to Mexican nationals working their way through the legal immigration process, all roads go through Juárez. That’s because the United States consulate there is the only one in Mexico that handles immigrant visas—the documents that allows a foreigner to live in the US while awaiting permanent legal residency.

The sprawling compound—it’s the largest consulate facility in the world—is located in an upscale neighborhood known as zona dorada, the golden zone. It looks like Anytown, USA. Walk a block and you can choose between Starbucks, McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and Denny’s. A bit further southwest and you’re at a new mall anchored by a Sears, boasting a cineplex with an IMAX® theater and a Total Fitness gym complete with a climbing wall.

But this sense of normalcy is an illusion. The $66 million fortress of a consulate is surrounded by a moat of heavily armed men, who guard it against an almost unimaginably brutal civil war raging just outside the golden zone. Ciudad Juárez, population 1.3 million, is sometimes called the “murder capital of the Americas”—a fitting description for a city that has seen roughly 7,000 killings in less than three years, including more than 3,100 last year.

Located just across the Rio Grande from El Paso, Texas, Juárez is ground zero in a bloody clash between the Mexican government and the drug cartels that feed Americans’ craving for cocaine, heroin, and marijuana. The “narco-war” includes turf battles between rival cartels. Since late 2006, when President Felipe Calderón launched a military offensive against the cartels, officials put the national death toll at more than 30,000.

An internal Department of Homeland Security assessment notes that one of the cartels “has used terror tactics generally seen in Iraq and Afghanistan—mass video-recorded decapitations, targeting of civilians…to instill fear among rivals, law enforcement and the general public.” One Mexican human-rights worker interviewed by London’s Guardian newspaper summed up the Juárez situation as “martial law, without the law.”

The violence in northern Mexico is worse than officials from either country will publicly admit, but a recently leaked State Department cable indicates that both sides understand the stakes. At a September 2009 meeting in Mexico City, that country’s undersecretary for governance, Gerónimo Gutiérrez Fernández, warned a US delegation that Mexico was in danger of “losing” entire regions like Juárez to the cartels.

In 2009, more than 94,000 Mexicans came to Juárez to apply for permanent resident status. Many, like Monica’s husband Alvaro, were undocumented and living gainfully in the United States. In past decades, applying would have been no big deal for such people. Thanks partly to Monica Bosquez and her husband Alvaro a 1965 Great Society law that emphasized the need to keep families intact, applicants already living in the United States could petition for a change of status without having to leave.

Monica Bosquez and her husband Alvaro a 1965 Great Society law that emphasized the need to keep families intact, applicants already living in the United States could petition for a change of status without having to leave.

But over the years, foes of illegal immigration have chipped away at the policies to the point where keeping families together is no longer a key consideration. Since 2001, undocumented foreigners living here for a year or more have been instructed to return to their native countries, where they must then wait a decade before becoming eligible to apply for a change in status. (Applicants may request a waiver of the 10-year waiting period, but may do so only after leaving the country.)

Immigrant visas were once processed at all nine US consulates in Mexico, but in 1988, the task was consolidated to two consulates, in Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana. In 1992, the Tijuana unit was closed. One State Department official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told me that the consolidation was a purely administrative move, and applies to “all countries where we have more than one consulate, except where there are regional language differences.”

On immigration-related websites like the Juarez, Mexico Discussion Forum and Immigrate2US, members often speculate as to why, of all of the cities in Mexico, they are forced to go to the Murder Capital. Some see it as a deliberate move to discourage people from applying. “This process is built to break one down,” wrote a member of the Juárez forum. “And most importantly, to instill fear.”

State Department spokeswoman Nicole Thompson dismisses this claim. “The decision was made years ago,” she told me, “before the increased drug-related violence along the border area.” But the decision still stands now that the city is a war zone. A different spokeswoman, for the Juárez consulate, insisted that the golden zone is “relatively safe.” Besides, she explained, “Visa applicants are not the targets. The war is between the cartels and gangs.”

When I run that notion by Martín Orquiz, a reporter for the Juárez newspaper El Diario, he replies that it’s generally true, but that many of the victims have been bystanders. “They were killed,” he said, “because they passed by where a shooting occurred.” He confirms that the area around the consulate is “relatively safe.”

To reach that safe zone, though, applicants must pass through sections of town that regularly see mass killings, through armed security checkpoints, and near the site of a car-bomb explosion that killed three people in July. “The quality of the neighborhood around the compound doesn’t much change the whole business of getting into and out of the city,” one visa applicant told me. “The scariest part of our trip was the ride from the airport to the consulate, then back again.” Especially, he explained, when his bus was suddenly behind a military truck filled with armed soldiers wearing black balaclavas.

The consulate’s website is vague on the safety issue. Under “Frequently Asked Questions,” it asks: “Is it safe for my family and I to travel to Ciudad Juárez given the recent reports of violence?”

The answer: “All immigrant visa cases in Mexico are currently processed at the U.S. Consulate General in Ciudad Juarez. Therefore all applicants must present themselves at the Consulate at the time and date of their appointment if they wish to proceed with their cases. It is incumbent upon you to take the necessary precautions when traveling to your visa appointment.”

The State Department, meanwhile, urges US citizens to “defer unnecessary travel” to Juárez because of the violence: “DTOs (drug-trafficking organizations) have erected unauthorized checkpoints, and killed motorists who have not stopped at them…. Ciudad Juarez is of special concern…. In confrontations with the Mexican army and police, DTOs have employed automatic weapons and grenades. In some cases, assailants have worn full or partial police or military uniforms and have used vehicles that resemble police vehicles…. Innocent bystanders have been killed in shootouts between DTOs and Mexican law enforcement or between rival DTOs…. U.S. citizens should be aware that many cases of violent crime are never resolved by Mexican law enforcement, and the U.S. government has no authority to investigate crimes committed in Mexico.” And so on.

“The websites say stay away, don’t travel there,” one woman complained to me. “But for families who are trying to do the right, legal, thing and go through the immigration process, they do not give us any other option.”

If anyone imagined that US citizenship offered impunity from the violence, that myth was laid to rest last March 13. Lesley Enriquez and her husband Arthur Redelfs, both American citizens, were leaving a children’s birthday party in Juárez with their seven-month-old daughter strapped into a car seat. (Enriquez was also four months pregnant.) Sometime after 2 p.m., a car roared up behind their white Toyota RAV4, which bore Texas plates, and gunmen opened fire on the family.

The adults were killed; their baby daughter wasn’t hit. Ten minutes later, gunmen attacked a white Honda Pilot coming from the same party, killing its driver, Jorge Salcido, and wounding his two young children in the back seat. The victims had a connection beyond the party: Lesley Enriquez and Salcido’s wife both worked at the consulate.

Three days after the murders, Monica Bosquez and her husband landed in Juárez. Alvaro’s interview was scheduled for St. Patrick’s Day, and Monica was wearing socks with green shamrocks for good luck. The couple stayed at a Holiday Inn inside the golden zone guarded by men with machine guns—even the bellboy carried a sidearm. None of it made her feel safe. In fact, Monica confessed, she was “absolutely terrified” for several days after the interview, waiting to see if Alvaro’s application would be approved.

On the afternoon of March 22, Monica posted a message to the Juárez discussion forum: “Can’t wait for this to be over.”

Later, she send me a personal message: “The fear is the hardest part.”

In emails to friends and in online postings, Bosquez had begun to refer to her family’s ordeal simply as “the nightmare.” It’s clear that this included more than just Juárez. Months would often go by, for instance, without any status updates or responses to questions from immigration officials. In addition to the endless delays, applicants regularly complain of rude treatment by consulate staff, and of being given incorrect information that results in further delays or denial of an application.

“I’m going crazy,” Monica posted as one point as she waited to learn whether, and when, she and her husband would be reunited. “Why aren’t we showing up in the…system yet?” she wrote. “I wish this nightmare would finally end.”

This part of the nightmare is the result of a tangle of laws and regulations that has grown mind-numbingly complex over the decades. Part Kafka, part Alice in Wonderland, it frustrates applicants and consulate staff alike. The problem is exacerbated by chronic understaffing. “The consular section in Ciudad Juarez is the largest in the world,” stated a 2009 report by the office of the State Department’s Inspector General, “yet its staffing is still too small for the workload.” Juárez officers are forced to process twice as many applications per day as their counterparts in other countries, “threatening to burn people out.”

The report also revealed a growing desire among consular employees to live across the border in El Paso, citing “grisly narcotics-related violence.”

Monica often comforted her peers on the Juárez forum, women trapped in their own versions of the nightmare. “I can’t imagine how terrible it seems right now,” she replied to a woman who felt she had lost the battle to be reunited with her husband of 11 years. “Don’t give up—this is another bureaucratic hurdle this stupid system is throwing at you, but you can beat it!”

Over at the Immigrate2US forum, Susan O’Brien (a pseudonym) took on a similar role, posting as Liley99. In 1998, at age 17, her husband Sabas had embarked on the treacherous journey across the Sonoran desert and entered the United States. He’d worked hard and saved his money. He married O’Brien and, by 2007, the couple had their own home, a successful carpet-cleaning business, and a baby boy.

In late 2007, Sabas left the United States so that he could apply for legal immigrant status. “He is living the all-American dream!” O’Brien wrote in a filing to the Juárez consulate. Wanting to remain closer to his wife and child, Sabas decided to look for work in Juárez rather than travel far from the border. Using money from their savings, he rented an apartment in a gated area. But O’Brien still worried. “My husband told me that in just March, 250 people have been killed in Juárez alone,” she posted to her forum.

Because the US consulate in Juárez was so short-staffed, Sabas’ application was placed on backlog, a bureaucratic limbo. “I had no idea what immigration was,” O’Brien wrote on the forum on May 17, 2008, after six months apart from her husband, “nor did I understand the obstacles in front of us now…”

Five hours later, she posted another message to the forum, this one frantic. The subject line read: “Please pray, oh god please pray.” Sabas had been kidnapped along with two other men. For hours, O’Brien called her husband’s cell phone with no response. When she finally got through, the man on the other end of the line was a police detective.

Throughout that night and into the early morning hours, as O’Brien posted what few details she managed to learn, dozens of forum members stayed up to support her.

At 2:15 a.m., she notified the forum that the Juárez police had found a car with three unidentified bodies. “God please let this NOT be him,” O’Brien wrote. “I am lost, I don’t know what to do.”

By 5:22 a.m., the identity of one of the bodies had been established; it was the owner of the apartment complex where Sabas lived. “I only hope that he is not one of the other 2,” she wrote.

At 8:05 a.m., more bad news. The victims’ last names hadn’t been released, but one had been identified by the first name Sabas. O’Brien awaited the inevitable: “I can’t sleep and still feel like I am dying slowly.”

Just after midnight, she posted a message saying that her husband’s body had been positively identified. His hands and feet were bound and he had been shot in the head and tossed into the car trunk. Supporters of Liley99 filled the forum boards with expressions of grief, sympathy, and calls for changes to the system they blamed for Sabas’ death.

“…they really need to move this consulate to a safer area or do our appointments in the US, i am so scared to send my husband off to this horrible place, i could not stand to lose him, my heart goes out to you.”

“…this could have been anyone of us. I can’t imagine to carry that pain that she must be carrying right now. This is one of my worst nightmares. I cannot wrap my head around this.”

“This is what US citizens and their spouses get for trying to do things the legal way?! This is the reward for trying to go through the system?!”

Moving the visa-processing center to a safer consulate may seem like a solution, but the State Department insists it’s not practical. “They’re all dug in,” explains Houston immigration attorney Laurel Scott, referring to the new state-of-the-art facility. Even if officials were willing to move the unit, she adds, where would they put it? “The situation in Mexico is destabilizing very quickly and severely,” Scott says, “and not just in Juárez.” By the time you could build a new facility anywhere in northern Mexico, that area could be as dangerous as the current location.

Take Monterrey, Mexico’s third largest city, located 130 miles south of the border. It was named the safest city in all of Latin America just five years ago, according to an international business journal. But drug violence recently swept in, prompting a mass exodus of business leaders. Last April, a score of armed men stormed a Holiday Inn and kidnapped several guests. Murders in broad daylight are now commonplace. In August, employees at the Monterrey consulate were ordered to evacuate their children after an attempted kidnapping left two bodyguards dead outside the elite college-prep American school. If even Monterrey is no longer safe, experts say, moving visa processing is a non-starter.

Short of a government victory over the drug cartels, something nobody expects anytime soon, people living “the nightmare” would like to see the US go back to its old policy of allowing people to apply from inside the United States.

But the trend appears to be headed in the opposite direction. The Senate recently killed the DREAM act, the legislation President Obama touted in his State of the Union address, which would open the door to citizenship for undocumented foreigners who arrived here as children—so long as they meet certain conditions, like attending a four-year college or serving in the US military.

One of the bill’s original sponsors, Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, explained his continued support for the bill at a town hall meeting last July. “A lot of these kids are brought in as infants,” he told the crowd. “They don’t even know that they’re not citizens until they graduate from high school. If they’ve lived good lives and they’ve done good things, why would we penalize them and not let them at least go to school?”

But in December, when the bill came to a vote on the Senate floor, Hatch wasn’t there. The senator, who faces a primary challenge in 2012, now says that even if he had been present, he would have voted against the act he helped write.

Meanwhile, the House committee that handles major immigration issues, has a new chair. He is Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Tex.), champion of a 1996 legislative crackdown on illegal immigration that created the arduous visa process now in place. Since then, Smith has cosponsored a bill that would deny citizenship to babies born to undocumented parents on US soil. Opponents call it draconian and unconstitutional. Smith simply says it’s necessary.

In the meantime, the thousands of families intent on doing things “the right way” struggle to stay positive. Things sometimes do work out. The State Department granted O’Brien permission to have her husband’s body returned to her. “And he did come back to the states,” she posted to her forum, “not as planned but he was able to return to the world that he knew and loved.”

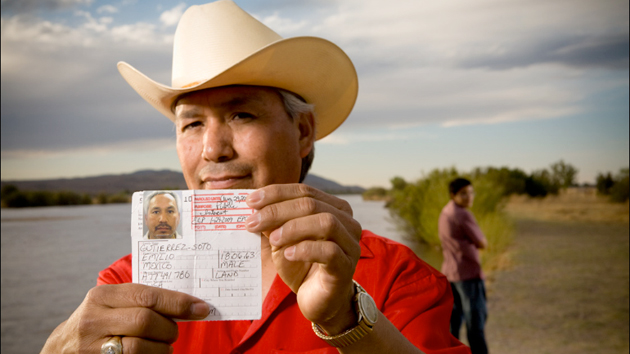

For Monica Bosquez and her family, it was a happy ending. On December 7, she sent me a picture of Alvaro from her cell phone. He looks exhausted and red-eyed, but manages a weary smile. He’s holding open his Mexican passport so that the contents are visible. The picture is grainy and blurred but you can still make out the word “VISA.” To the left is a smaller version of Alvaro’s smiling face, to the right an engraving that is just recognizable: the dome of the US Capitol and beside it, the Liberty Bell.

Along with the photo comes a short message: “We made it. :)”

This reporting was supported in part by contributions from the Spot.Us community.