Chen Jianli/Xinhua/Zuma

Seismically speaking, it’s been a rough few months on the Pacific rim. On February 27, 2010, an 8.8-magnitude earthquake struck Chile. In September, two major quakes rocked New Zealand’s South Island, and a 6.3 followed in February in Christchurch. Just a few weeks after that, the devastating 9.0 quake struck Japan, causing a tsunami and a nuclear crisis. These quakes occurred on three of the four “corners” of the notoriously jumpy Ring of Fire. The other corner? The West Coast of the United States. So does this series of earthquakes up the US’s chances of the dreaded “Big One”?

This Newsweek story from last week suggests that the answer is yes, since the earth is “like a great brass bell, which when struck by an enormous hammer blow on one side sets to vibrating and ringing from all over.” Rogue seismologist Jim Berkland, who claims to be able to predict earthquakes based in part on tides and the moon, has also warned that a major US quake is imminent.

The seismologists I talked to all agreed that major quakes do have local ripple effects. In addition to aftershocks, which can contine for a few weeks after a quake the size of Japan’s, earthquakes can also beget more earthquakes on other parts of the same plate, or even on nearby faults. John Mutter, a professor of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, explains that when a quake occurs, stress is relieved in one area of a plate and transferred to other parts of that plate. “So, unhappily, we know that Port-au-Prince is at even greater risk than it was before the quake last year,” says Mutter. “And the recent earthquake in Christchurch was probably ‘triggered’ by the one that occurred in September the year before.”

The question, then: How far can the transferred stress travel? This diagram (PDF) made by by Ross Stein, a geophysicist United States Geological Survey, shows increased levels of stress as far as 186 miles from the epicenter of the March 11 quake in Japan. The New Zealand earthquakes all occurred within a few hundred miles; they were probably connected. Similarly, says Morgan Moschetti, another USGS geophysicist, the quake that struck the Indian Ocean and triggered a tsunami in 2004 likely triggered another series of quakes in Sumatra in 2007.

Some scientists believe the stress transfer zones can extend even further. UC-Santa Cruz seismologist Emily Brodsky recently told New Scientist that “The recent spurt of magnitude-8-plus earthquakes may be an extended aftershock sequence of the 2004 Sumatra earthquake.” But seismologists aren’t in agreement about this point, and the bottom line is that there’s not enough data to say conclusively whether they’re all related.

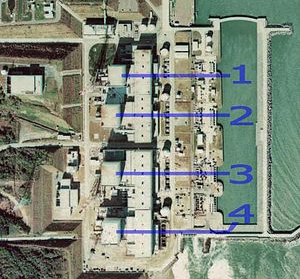

And there’s certainly no evidence that a quake can transfer stress across as great of a distance as that between Japan and the US. “That’s too far for stress to act,” says Mutter. Which is not to say that the Big One isn’t imminent, or that we shouldn’t take precautions. The West Coast straddles several fault lines, and as Julia Whitty points out here, earthquakes are nothing if not surprising. Speaking of which, the Sunlight Foundation has a really interesting map of US nuclear reactors, fault lines, and seismic activity. Worth a gander.

Got a burning eco-quandary? Submit it to econundrums@motherjones.com. Get all your green questions answered by visiting Econundrums on Facebook here.