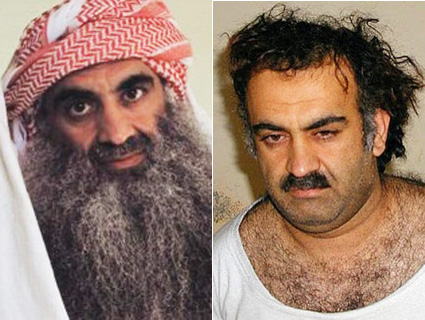

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, in a Red Cross photo taken at Guantanamo Bay (left) and a photo (right) reportedly taken by US forces shortly after they first captured Mohammed in early 2003.Red Cross photo (left)/US Government photo (right).

Last week, on the same day President Barack Obama launched his re-election campaign, his administration announced that it had officially reversed its decision to try the accused 9/11 plotters—including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-proclaimed “mastermind” of the attacks—in federal court and would instead prosecute them via the military commissions system.

But, as the military commissions gear up for what could be their first cases to end in death sentences, a shadow hangs over the lawyers representing these most unsympathetic of defendants. For well over a year, civilian and military defense lawyers representing so-called “high-value detainees” at Guantanamo Bay were caught up in a secret Justice Department investigation. (The agency won’t say whether the investigation is still ongoing.) Can Guantanamo lawyers mount full and fair defenses of the 9/11 conspirators while under the pressures of a past or present DOJ investigation—and the threat of a future probe by the Pentagon itself, as some congressional Republicans have called for? We’re about to find out.

The genesis of the DOJ probe dates back at least to the summer of 2009, when guards at Guantanamo found a series of photos in the cell of Mustafa Ahmad al Hawsawi, an accused Al Qaeda financier and one of KSM’s four co-defendants. The photos, according to multiple reports, showed CIA employees suspected of involvement in the interrogation of high-value detainees, including al Hawsawi himself.

The CIA, unsurprisingly, was deeply alarmed. John Rizzo, then the agency’s top lawyer, demanded an investigation. He later described the incident as “far more serious than Valerie Plame,” referring to the Bush-era leak of an operative’s covert status. He wasn’t alone in his concerns. “This is an agency that has reasons to be concerned as to whether or not somebody’s got their back,” another high-ranking former intelligence official told Mother Jones last year. “It’s always operating out there on the edge, not unlawfully, but generally at the farthest reaches of executive prerogative.”

The Justice Department launched an investigation, headed by Donald Vieira, a former Democratic Hill staffer. Vieira soon found that the photos had been taken for a reason. Since any successful defense of a high-value detainee would likely require proving torture—and calling the alleged torturers, if they existed, to the stand—members of the Gitmo defense bar felt they needed to identify whom, exactly, had interrogated their clients.

In any other criminal case, this would normally be a breeze—defense lawyers generally know which cops or FBI agents questioned their clients and can call them as witnesses if necessary. But when you’re dealing with the CIA, it’s a whole different story. The details of many of the high-value detainees’ interrogations are secret. Ditto the identities of the interrogators. The defense attorneys needed to identify the interrogators, and the prosecution wasn’t interested in lending a hand. Susan Crawford, the convening authority (a sort of judge-like figure) for the military commissions, was a close friend of David Addington, the man known as “Cheney’s Cheney.” She certainly wasn’t going to help.

John Sifton, a longtime human rights investigator, attorney, and firebrand, stepped into the breach. As Daniel Schulman and I reported last year, Sifton was the major force behind a highly controversial effort to identify, photograph, and, in some cases, tail CIA officials and contractors whom he and others believed had been involved in the torture of Guantanamo detainees.

Sifton’s clients included the John Adams Project, a joint program of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL). In 2008, when the first military commission charges were brought against the 9/11 suspects—and the John Adams Project launched—none of the military defense lawyers at Gitmo had ever defended a capital case through to the penalty phase. The purpose of the project was to fund top-tier capital defense attorneys to assist military lawyers in defending the 9/11 plotters and other “high-value detainees” before the military commissions. It was named after the founding father who defended British soldiers in court in the wake of the Boston massacre.

When news of the Vieira investigation first broke, Anthony Romero, the ACLU’s executive director, insisted no laws or regulations had been broken. “The real scandal,” he said in a statement, “isn’t that we’re investigating the torture of our clients, but that the government isn’t.” By mid-March 2010, it had become clear that Vieira wasn’t convinced any of the Guantanamo lawyers had broken the law. Elements within the CIA weren’t happy. On March 15, the Washington Times‘ Bill Gertz—a journalist with good sources in the CIA and the Bush administration—published an extensive article outlining the agency’s gripes with Vieira.

Under serious pressure from inside and outside the government, Attorney General Eric Holder appointed Patrick Fitzgerald, the US attorney who handled the Plame matter and the Rod Blagojevich case, to take over the investigation into the Gitmo lawyers. Holder was sending a message, to the Gitmo bar and the Right: He took the matter very seriously.

The investigation is highly secretive, and Fitzgerald runs a famously leak-free ship. A Justice Department spokesman would only say that “Patrick Fitzgerald, the US Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, has been assigned responsibility for this matter,” a statement that suggests the investigation may be ongoing. Randy Samborn, Fitzgerald’s spokesman, said Fitzgerald’s office had no comment on whether an investigation is still underway.

There are some signs of activity. In the year since Fitzgerald took over, people and organizations connected to the case began to change their behavior. Sifton sharply reduced his role in the private investigation firm he founded, One World Research, to take an investigative job with a white-shoe law firm. For some time during 2010, Mother Jones has learned, Sifton was being represented by a top Washington lawyer with deep connections in the Justice Department.

Today, friends and associates say, the once-fiercely defiant Sifton is oddly quiet, and no longer speaks about the identities of the people whom he once believed to be involved in the interrogation program. The ACLU and the John Adams project have also clammed up. After first aggressively defending their actions in the press, the groups moved to a strict no-comment strategy after Fitzgerald took over the investigation. But privately, Romero has continued to complain that Guantanamo defense lawyers associated with the ACLU were under enormous legal pressure from the DOJ.

Given the circumstances, “Any sort of reasonable person would pause and think about what might happen to them in the zealous protection of their client,” says Andrea Prasow, a senior counsel at Human Rights Watch. If defense lawyers at Guantanamo believed that they needed photos of CIA interrogators in order to meet their ethical obligations to mount a vigorous defense of their clients, “It’s hard to think they’d be confident given what happened to their colleagues,” Prasow said.

Stephen Saltzburg, a law professor at George Washington University who testified before Congress about the military commissions last week, says he’s “sure” that the military lawyers currently assigned to the 9/11 defendents would argue that they were not intimidated by the DOJ investigation. But if he were a defendant, Saltzburg says, he would “want to know whether my lawyer had been under investigation, because I wouldn’t be so sure how it was going to effect how the lawyer was handling my case.”

The DOJ probe isn’t even the only option on the table for investigating the Gitmo defense bar. Last year, Republicans in Congress pushed hard for a provision that would have essentially instituted a permanent Defense Department investigation of the activities of all Guantanamo defense lawyers.

The measure failed, but it proved an important point: Even a Fitzgerald-led, CIA-instigated, months-long DOJ investigation of Guantanamo defense lawyers isn’t aggressive enough for some folks. In 2007, Charles Stimson, then the top Pentagon official in charge of Guantanamo detainees, resigned after he attacked top law firms for allowing their lawyers to represent terrorism suspects. “Corporate CEOs seeing [their law firms representing detainees] should ask firms to choose between lucrative retainers and representing terrorists,” Stimson said. The fact is, there are some who believe it’s not just the 9/11 defendants who are the enemy—their lawyers are, too.