Random House Group

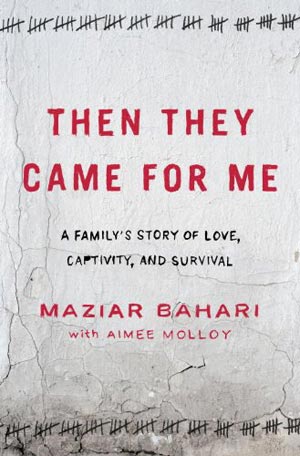

In 2009, Newsweek journalist Maziar Bahari spent more than three months in Iran’s most notorious prison, Evin. His harrowing experience is the subject of his new memoir, Then They Came for Me (Random House).

Before being arrested, Bahari worked as a Newsweek reporter in the Islamic Republic. Mindful of the dangers of being a journalist in Iran, Bahari, who’s Iranian-Canadian, produced documentaries and articles with sensitivity to the government’s strict press laws. But when Iran’s 2009 presidential election approached, pitting the unpopular incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad against the more progressive Mir Hossein Mousavi, Bahari had a difficult decision to make. Ahmadinejad’s previous term had not been a good one for the country; the economy performed poorly, unemployment was high, and frustration among the country’s populous youth was growing. A progressive who promised to open Iran up to the world, Mousavi’s chances looked good. But Bahari hesitated to cover the story. His wife, Paola, was pregnant with the couple’s first child at their home in London. He ultimately decided to go to Tehran, promising his wife that he’d come back to spend three uninterrupted months with her afterward.

Ahmadinejad of course won the election, and demonstrations erupted across the country, with an especially strong representation among the youth, who felt that the election had been stolen. Bahari paints a vivid picture of protesters waving banners reading “Where Is My Vote?” His connections and in-depth understanding of the people, culture, and politics in Iran allow him to make acute observations, such as when he marches with the protesters: “There was no chanting, no angry words—just a peaceful ribbon of green flags, bandanas, wristbands, and scarves moving from Revolution Square toward Freedom Square with an air of quiet and calm.” Soon after the protest, Bahari was arrested by the Revolutionary Guard at his mother’s house in Tehran and taken to Evin prison, where he would spend the next three months of his life.

Bahari is tormented in prison by a man he can identify only by scent: Rosewater. For months, Rosewater berates and beats Bahari for being a “spy.” Then They Came for Me takes us through the sense of abandonment, anger, and paranoia one feels in Evin, Iran’s decades-old, secretive torture chamber used by multiple Iranian regimes. In fact, Bahari’s father was tortured by the Shah of Iran in Evin. His sister spent years in the prison under the Khomeini regime as well. In 2003, Zahra Kazemi, another Iranian-Canadian journalist, was killed in Evin after she took a picture of the prison. After three months of his own personal hell, Bahari was lucky to be released on October 20, 2009.

His account is filled with intriguing and at times absurd anecdotes, like the time authorities accused Bahari of helping a spy navigate the country—the “spy” was actually Jason Jones from The Daily Show who had interviewed Bahari in Tehran for a skit about the elections. Or the time Bahari heard the voices of Americans in the prison, who turned out to be the three hikers who have been in Evin for nearly two years (one of the hikers, Sarah Shourd, was released last year).

While Bahari’s vivid descriptions make for a good read, perhaps the most compelling aspect of Then They Came for Me is Bahari’s ability to capture the frustration that many Iranians, at home and abroad, feel toward Iran’s current government. Bahari describes a nation run by “thugs” much more concerned with the implementation of religious and political tyranny over pluralism, freedom, and a stable economy. Then They Came for Me is not only a fascinating, human exploration into Bahari’s personal experience but it also provides insight into the shared experience of those affected by repressive governments everywhere.