Illustration: Jeffrey Smith

The Gold Digger

Pattern: Target is broke and thinks he can make big money by catering to informant’s suggestions.

Case study: Derrick Shareef was 22 and desperate for cash to fix his car when an informant approached him at the video game store where he worked in the fall of 2006. The informant, a career criminal, offered Shareef a vehicle, a place to live, and free meals at his house. It was the day before Ramadan, and Shareef, who’d been on the outs with his family since converting to Islam at age 15, saw the offer as an act of God. Weeks later, he told the informant he wanted to attack a courthouse and “smoke a judge.” The informant suggested attacking a shopping mall at Christmas instead. Shareef excitedly agreed; since he was still broke, he traded an “arms dealer”—in fact an undercover FBI agent—a set of speakers for some grenades and a 9 mm handgun.

Charge: Attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction

Sentence: 35 years

The Convert

Pattern: Target is a newcomer to Islam with only a rudimentary understanding of the religion; often also broke and/or homeless.

Case study: Michael Finton converted to Islam while in prison for robbery and, while out on parole, wrote letters to John Walker Lindh, the American student who joined the Taliban. Parole officers found out about the letters while searching his car and told the FBI. The bureau sent in an informant—another prison convert who, according to an FBI affidavit, may have been dealing drugs while working for the bureau. Together with yet another undercover operative, Finton hatched a car-bomb plot targeting the federal building in Springfield, Illinois.

Charges: Attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction

Sentence: 28 years

The Oath Taker

Pattern: Target swears a fictitious Al Qaeda oath made up by informant; is charged and convicted based on that oath

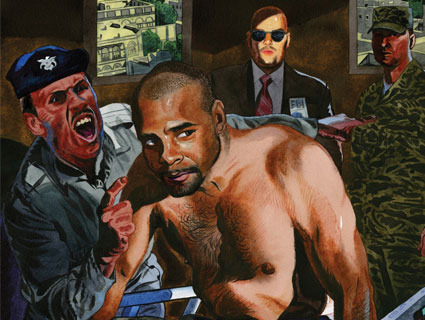

Case study: Tarik Shah, an accomplished jazz bassist (he played Bill Clinton’s inauguration) and martial-arts studio owner, met FBI informant Mohamed Alanssi through an Islamic bookstore in New York City. For two years, Alanssi kept in contact with Shah but got nothing incriminating out of him. So the FBI turned to a second informant, Theodore Shelby, an ex-convict and former Black Panther. He recorded conversations that showed Shah as a man obsessed with his martial-arts prowess and a desire to train Muslims in hand-to-hand combat. In one exchange, Shah talked about how he could use the sharp pin that his bass rested on to kill someone. Eventually, Shelby introduced him to an Arabic-speaking FBI agent who led Shah and a friend in an oath to Al Qaeda. The oath became a key piece of evidence in his conviction.

Charge: Conspiring to provide material support to terrorists

Sentence: 15 years (PDF)

The Car Bomber

Pattern: Target and informant hatch plot together; FBI supplies vehicle, “explosives,” and phone to trigger the supposed bomb.

Case study: Hosam Smadi, an 18-year-old Jordanian living outside Dallas, came to the FBI’s attention in an extremist chat room. An undercover agent befriended Smadi and introduced him to two more agents posing as members of an Al Qaeda sleeper cell. They hatched a plan to bomb Fountain Place, an iconic Dallas skyscraper. On September 24, 2009, the FBI provided Smadi with what they said was a car bomb; he drove it into the building’s parking garage and dialed the number he believed would trigger the bomb.

Charges: Attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction

Sentence: 24 years

The Trainee

Pattern: FBI agent or informant offers to train target as a jihadist, most often via weapons instruction and bodybuilding.

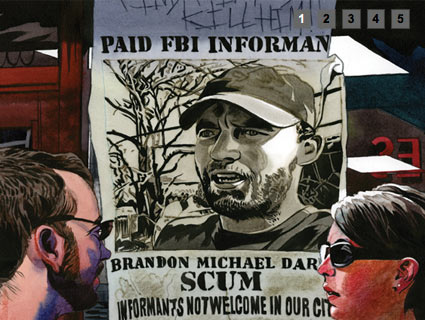

Case study: Marwan el-Hindi was a Jordanian-born naturalized citizen with a string of fraudulent businesses. He met Darren Griffin, a former US Army Special Forces member and FBI informant, at his mosque and asked him about weapons training. From then on, Griffin stayed close to el-Hindi, taking online terrorist training classes with him, working out at a gym, and doing target practice. Griffin, who is referred to in bureau documents as “the Trainer,” spent more than three years cultivating his target before the FBI arrested el-Hindi in February 2006.

Charges: Conspiring to kill, kidnap, maim, or injure another person outside of the United States; conspiring to provide material support to terrorists; distributing information on explosives

Sentence: 13 years

The Subway Bomber

Pattern: With the exception of one attempt to bomb the New York City subway, all the headline-grabbing subway “plots” you’ve heard of were FBI-led nonstarters.

Case study: Farooque Ahmed was a 34-year-old Pakistani computer engineer living in a middle-class suburb of Washington, DC, with his English-born wife and baby. He’d worked for Ericsson and a Verizon contractor, according to his LinkedIn profile. In the spring of 2010, he came to know two men he believed to be Al Qaeda representatives, and they met several times in northern Virginia hotel rooms, where Ahmed provided pictures, videos, and sketches of Washington Metro stations. He also told the men, who were FBI assets, that he had been training for an attack by studying martial arts as well as knife and gun techniques. He was arrested with great fanfare, though the government took care to point out that “at no time was the public in danger.”

Charge: Attempting to provide material support to a terrorist organization; collecting information to assist a terrorist attack

Sentence: 23 years