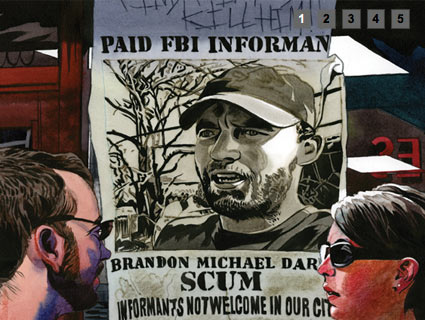

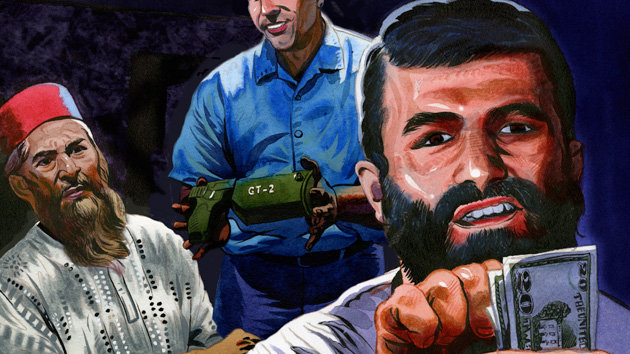

Illustration: Jeffrey Smith

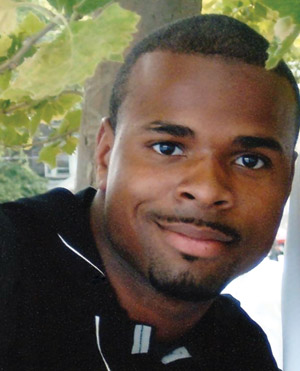

When Gulet Mohamed finally returned home on a chilly Virginia morning in January, the 19-year-old from Fairfax was wearing the same outfit he had on when he disappeared a month earlier in Kuwait. Clad in a fleece hat and a gray Real Madrid sweatshirt, the straggly-bearded, wide-eyed teenager stepped out of arrivals at Dulles Airport and into a phalanx of television cameras. He wore a bewildered smile—as if he was still unsure of what had happened to him but was just grateful it was over.

For more than a year, Mohamed had been living in Kuwait City with an uncle. On December 20, 2010, according to legal records (PDF), he went to the airport to renew his tourist visa for an additional three months. The process took longer than usual. From a waiting area, Mohamed emailed his brother to let him know he’d run into some red tape.

Soon afterward, two men in street clothes came in, blindfolded him, escorted him out of the airport, and led him into the back of a vehicle. They drove maybe 15 or 20 minutes. When the men removed his blindfold, he was in a cell with white walls.

Later, the men—members of Kuwait’s security forces, Mohamed inferred—marched him to an interrogation room, where they shouted names at him in Arabic.

“Osama bin Laden! Do you know him?” “Anwar al-Awlaki?”

When he responded “no,” his interrogators slapped him across the face. As the days passed, Mohamed claims, they beat him with sticks on the soles of his feet, asked him to choose between torture by electrocution or power drill, and threatened his family.

Sometimes, Mohamed later told his lawyer, his captors escorted him, blindfolded, to another part of the facility, where a man who spoke with an American accent posed specific questions about his life in the US. He inquired about Mohamed’s siblings by name. “Don’t you know we know everything about you?” he asked.

Mohamed is one of a growing number of American Muslims who claim they were captured overseas and questioned in secret at the behest of the United States, victims of what human rights advocates call “proxy detention“—or “rendition-lite.” The latter is a reference to the Bush- and Clinton-era CIA practice of capturing foreign nationals suspected of terrorism and “rendering” them to countries such as Egypt, Jordan, or Morocco (PDF) for interrogations that often involved torture.

Many of these episodes follow a similar script. A US citizen is detained, questioned, and sometimes abused in a Middle Eastern or African country by local security forces. Often his interrogators possess information that could only have come from US authorities; some of the detainees say American officials have been present for the questioning. When the suspect is released from detention, he often discovers he’s on the no-fly list and can’t return home unless he submits to further questioning by FBI agents. Sometimes he’s denied access to a lawyer during these sessions.

Gulet Mohamed. Jacquelyn Martin/AP PhotoIn the past, the FBI has denied that it asks foreign governments to apprehend Americans. But, a Mother Jones investigation has found, the bureau has a long-standing and until now undisclosed program for facilitating such detentions. Coordinated by elite agents who serve in terrorism hot spots around the world, the practice enables the interrogation of American suspects outside the US justice system. “Their citizenship doesn’t seem to matter to the government,” says Daphne Eviatar, a lawyer with Human Rights First. “It raises a question of whether there’s a whole class of people out there who’ve been denied the right to return home for the purpose of interrogation in foreign custody.”

Gulet Mohamed. Jacquelyn Martin/AP PhotoIn the past, the FBI has denied that it asks foreign governments to apprehend Americans. But, a Mother Jones investigation has found, the bureau has a long-standing and until now undisclosed program for facilitating such detentions. Coordinated by elite agents who serve in terrorism hot spots around the world, the practice enables the interrogation of American suspects outside the US justice system. “Their citizenship doesn’t seem to matter to the government,” says Daphne Eviatar, a lawyer with Human Rights First. “It raises a question of whether there’s a whole class of people out there who’ve been denied the right to return home for the purpose of interrogation in foreign custody.”

Although it’s difficult to say for certain whether the men in this story—which is based on interviews with law enforcement and intelligence officials, court documents, transcripts, and other records—are terrorists, tourists, or something in between, one thing is clear: Pakistanis, Saudis, and Somalis aren’t the only ones being captured and questioned on our behalf. Americans are too.

In October 2008, a few days before Halloween, a 27-year-old Somali American drove a car full of explosives into a government office in northern Somalia. The bomber’s name was Shirwa Ahmed, and he’d grown up in Minneapolis playing basketball and listening to Ice Cube. Ahmed is widely believed to be the first American suicide bomber (PDF).

What worries federal authorities is that Ahmed was one of at least 20 young men who left Minnesota between 2007 and 2009 for Somalia—intending, the FBI believes, to join the Al Qaeda-linked Islamist group al-Shabaab. Since then, several more of these men are believed to have become suicide bombers—including one just this past May.

Cases like Ahmed’s seem to be on the rise. Between 2002 and 2008, an average of 12 people per year were indicted on charges relating to “domestic radicalization and recruitment to jihadist terrorism,” according to a 2010 report by the RAND Corporation (PDF). That number rose to 42 in 2009. For counterterrorism officials, the face of Islamic terrorism was no longer a Saudi trained in the mountains of Afghanistan. It was Nidal Hasan, the Fort Hood shooter, radicalized over the internet, or Faisal Shahzad, the Pakistani American who attempted to detonate a car bomb in Times Square in May 2010 (PDF). A Senate Foreign Relations Committee report released in January 2010 warned that Al Qaeda (PDF) “seeks to recruit American citizens to carry out terrorist attacks in the United States” and singled out Yemen and Somalia as places where such recruits might travel.

Gulet Mohamed had spent time in both countries—which by itself would have raised “a lot of flags,” according to a former senior State Department official familiar with his case. He first visited Yemen in March 2009, planning to study Arabic and Islam. After a few weeks, however, he and his mother decided that the country was not safe, and he made his way to a relatively stable part of northern Somalia to stay with family. In August 2009 he moved on to Kuwait, where he remained until his arrest.

After a week of beatings and harsh interrogation, Mohamed was transferred to a Kuwaiti deportation facility. It was here, he says, that the FBI showed up. Agents interrogated him repeatedly, asking him why he had traveled to Somalia and Yemen and whether he knew Shahzad or Zachary Chesser, an American Muslim charged in July 2010 with aiding al-Shabaab. According to Mohamed, when he requested a lawyer, one of the agents told him: “You’re here; your lawyer is not.”

Mohamed was also informed that his name had been placed on the no-fly list—effectively blocking his return to the US. “Your government is not letting you back into your country,” one Kuwaiti official told him. Another said: “Gulet, we have relationships with the Americans. This interrogation is between you and your government.”

Sanaa, the capital of Yemen, is one of the gems of the Arabian Peninsula. Even as the country teeters on the brink of chaos, tourists still visit the ancient hill city to gape at the intricate rammed-earth houses that compose its crenellated skyline.

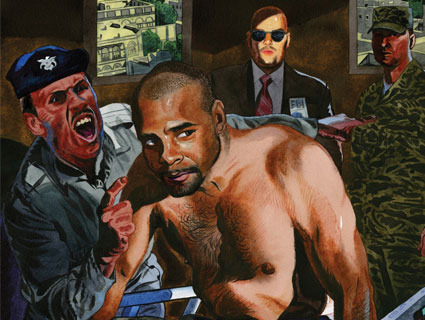

One January morning in 2010, Sharif Mobley was drinking tea outside a convenience store bedecked with a Coca-Cola sign when two white vans screeched to a halt on the dusty street. Eight armed men dressed in black jumped out. One grabbed Mobley’s jacket, but the 26-year-old—a black belt in tae kwon do—slipped away.

Sharif Mobley. Courtesy of the Mobley FamilyHe made it a couple of steps before two bullets fractured his femur. “I’m an American!” he yelled as he was dragged away. The men threw him in the van and sped off.

Sharif Mobley. Courtesy of the Mobley FamilyHe made it a couple of steps before two bullets fractured his femur. “I’m an American!” he yelled as he was dragged away. The men threw him in the van and sped off.

Mobley, who was in Sanaa with his wife and two young children, had been advised not to go to Yemen. “It is unstable,” his childhood imam had warned. But for young Muslims, Sanaa can be irresistible. Lonely Planet pitches Yemen as “a great place to learn Arabic,” and it is; the language schools are cheap, good, and plentiful. It has also become a place for young western Muslims to complete their radicalization—which is exactly what government officials say Mobley was doing.

After Mobley vanished, his family would not hear anything authoritative about him for nearly six weeks. But on March 11, 2010, news broke that an American had been involved in an action-movie-style escape attempt at al-Jumhori Hospital in Sanaa. It was Mobley.

According to Yemeni officials, Mobley had tricked his guards at the hospital into putting down their guns to join him for prayers. Then he grabbed one of the weapons, shot two guards—one fatally—and made a break for it. He didn’t get far before the entire floor was on lockdown. Yemeni counterterrorism forces—many of which are trained and funded by the US—descended on the hospital and eventually reapprehended Mobley.

After the firefight, information about Mobley’s past poured out in the press: He had once called an acquaintance who had fought in Iraq a “Muslim killer,” and he was employed as a maintenance worker at several nuclear power plants—a fact that inspired much speculation. By the end of the week, the AP reported that, according to “US officials,” Mobley had “traveled to Yemen with the goal of joining” Al Qaeda. Also incriminating was the anonymously sourced allegation that Mobley had communicated with Anwar al-Awlaki, the New Mexico-born Al Qaeda propagandist now hiding out in Yemen.

Awlaki and Mobley spoke on the phone and corresponded over email a number of times, Mobley’s defense lawyer, Cori Crider, told Mother Jones, but about religious and personal matters, not terrorism. She says the two men met in person once in 2008, more than a year before his arrest.

Initial news accounts mirrored the official version of the incident, reporting that Mobley had been captured in early March—when in reality he’d been in custody for six weeks. According to a notarized letter to Crider from two top officials at the police hospital in Sanaa, Mobley was “admitted to the hospital on the 26th of January to the 10th of February 2010 post gun shot with a femur fracture. The surgical therapy was done by one of our orthopedic surgeons on the 26th of January. After treatment the patient was discharged and handed back to the National Security of the Republic of Yemen.”

According to legal documents prepared by Crider, Mobley had been visited by two American agents, “Matt from FBI and Khan from [the Pentagon],” while chained to his bed in a secure wing of the hospital. Matt looked “kind of like Matt Damon,” and Khan was a “heavyset person of South Asian, possibly Pakistani, descent,” Mobley told Crider. When Mobley asked for a lawyer, the agents told him that he was not under formal arrest and would not be read his rights. Mobley claims Matt and Khan questioned him repeatedly over the next several weeks, threatening his family and telling him he would be raped in a Yemeni prison if he didn’t cooperate. Some of their questions focused on Awlaki. Eventually, according to the documents, Mobley was transferred to a Yemeni prison—but not before his catheter was removed so roughly that he started bleeding profusely from his penis.

In prison, Mobley told Crider, he was beaten and dragged down stairs before eventually blacking out on a metal slab while the blood from his penis soaked through the front of his prison garment. He was later taken to a second hospital, where, he said, Matt and Khan returned to interrogate him at least once more. Eventually, he tried to escape. “Imagine for a minute you were shot and held in secret for weeks on end, beaten up, threatened with rape, and told that your wife and two babies would face the same fate you had,” Crider says. “Most of us in that situation would go to extraordinary lengths to protect our families.”

Mobley, like Mohamed, has never been charged with any crime under US law. Yemeni officials told the AP that he hadn’t even been on their list of “wanted militants.” But as of this writing, he’s still in prison in Yemen, awaiting trial for allegedly killing a guard during his escape attempt.

Prior to the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, the FBI didn’t maintain much of a foreign presence. But in the years since, the bureau has increasingly relied on its network of legal attaches, or Legats—elite FBI agents stationed at US embassies and charged with forming counterterrorism alliances with local law enforcement and intelligence services.

Between 1993 and 2001, the FBI more than doubled the number of Legat offices from 20 to 45 (PDF), opening new bureaus in Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. Another 14 have opened since 9/11 (PDF). The FBI refers to Legats as “the foundation” of its “international program” and says they are “essential” to preventing terrorist attacks. Among their main duties, according to the congressional testimony of one former FBI official, is “coordinating requests for FBI or host-country assistance overseas.”

This could mean something as routine as setting up meetings between FBI honchos and foreign intelligence officials. But according to current and former FBI officials familiar with the process, sometimes it also entails encouraging a foreign security service to detain an American terrorism suspect and passing along questions for interrogators. According to bureau sources, top FBI, Justice Department, and sometimes even White House officials must authorize such requests before they’re passed on to the Legat in the country where the suspect is traveling.

In a statement to Mother Jones, the FBI stopped short of admitting that it has requested the detention of American terrorist suspects. The bureau acknowledged, however, that information it has “elected to share” with “foreign law enforcement services” has “at times” resulted in the “detainment of an individual.” It also said FBI agents have occasionally “been afforded the opportunity to interview or witness an interview” with detainees abroad. The bureau maintains that FBI agents have “acted in accordance with established FBI policy and guidelines” in these cases. The bureau declined to comment on specific cases.

“America since the fall of the Berlin Wall has been eager to find proxies to do our dirty work,” says Michael Scheuer, the ex-head of the CIA’s Osama bin Laden unit and the author of a recent biography of the late Al Qaeda leader. “We’ve been lucky to find Jordans and Egypts that were willing to do that—not just to help us, but also because the people we were aiming at were the people they were also aiming at.”

In theory, an FBI official says, foreign security forces are told that US citizens detained as part of this program are not to be harmed. But, the official acknowledges, foreign security forces are sometimes overzealous. Torture isn’t the point, though, the source explains—fear is. Throwing a guy from suburban Virginia into a Middle Eastern jail cell might shake loose information that wouldn’t come out in an FBI interrogation room in Washington, DC.

Whether the information is accurate is another matter. Weeks after being interviewed by FBI agents in the United Arab Emirates in 2008, Naji Hamdan, a naturalized US citizen who had run an auto-parts business in California, was abruptly arrested by the country’s security forces. Over a period of three weeks, he was repeatedly beaten and questioned (PDF). “If you don’t confess, I swear to God I’m going to bring your wife to this room, and you’ll see what we do to her,” the lead interrogator vowed at one point. During one interrogation, Hamdan says, an American was present. “I’ve lived enough in the US to recognize the accent of the person when he talks,” he says. “I had no doubt that the person who was talking to me was a Caucasian American.” Hamdan’s interrogators kicked him in the side until he passed out. When he came to, the “American” spoke: “You better do what these people want, or they’ll fuck you up.”

Hamdan eventually confessed to being a member of a variety of terrorist groups, including Al Qaeda, and spent another 11 months in prison before the UAE deported him to Lebanon. He later said his confession was fiction—after weeks of torture, he’d told his interrogators whatever they wanted to hear. The FBI, for its part, extensively investigated Hamdan’s activities in the US. He was never charged with a crime.

“From some of the other proxy detentions, it’s clear that the government has got it flat wrong about which individuals pose a threat,” says the ACLU’s Michael Kaufman, who’s on Hamdan’s legal team. “It wouldn’t be surprising if Naji was one of those horrible, horrible mistakes.”

Along with the cases of Hamdan, Mobley, and Mohamed, there are others that show indications of US involvement. Yusuf Wehelie, another 19-year-old Virginian, claims he was detained and beaten by Egyptian security forces in May 2010 after the FBI questioned him and his older brother Yahya at a hotel in Cairo. The Egyptians who beat and interrogated Wehelie “stated over and over that they worked for the United States government, and that they were questioning me at the request of the United States government,” he later said. The Egyptian interrogators asked Wehelie “the same questions that the American FBI agents had been asking.” Some focused on Mobley. After Wehelie was allowed to return home, his brother was forced to remain in Cairo for two more months. Yusuf later told a reporter he was interviewed by the FBI 10 times and submitted to a polygraph test before he was permitted to return home. (The Wehelies, through their lawyer, declined to comment.)

In 2007, Kenyan authorities arrested Amir Meshal, of New Jersey, and New Hampshire-raised Daniel Maldonado after they sought refuge in Kenya when Ethiopia invaded Somalia and displaced its Islamist government. (Both men claim they went to Somalia, which was comparatively stable before the Ethiopian invasion, only for the experience of living in an Islamic country.) Maldonado has since taken a plea deal and is serving a 10-year sentence for receiving training from Al Qaeda. But Meshal has not been charged with a crime. Backed by the ACLU, he is suing the government (PDF), claiming that FBI agents violated his rights by interrogating him in a series of African prisons without access to a lawyer.

Human rights advocates believe many more Americans may have been subjected to proxy detention but have not come forward for fear of retaliation or prosecution; some may still be secretly imprisoned. As Gulet Mohamed declared when he arrived back in the US: “There are still probably other people out there that are being tortured like I was. My voice has been heard, but their voices are not being heard.”

During his detention in Kuwait, one of Mohamed’s fellow prisoners had given him access to a smuggled cell phone. He called his family, who contacted a lawyer; eventually Mohamed used the phone to describe his plight to the New York Times‘ Mark Mazzetti. The story made headlines, embarrassing the Obama administration and raising questions about its track record on civil liberties and human rights. An irate US Embassy official later visited Mohamed’s cell with a highlighted copy of the Times story. “You didn’t cooperate with the FBI,” he said, according to Mohamed. “That is why you didn’t leave. You went public. We need to calm this down.”

At a press conference when Mohamed finally did return home, his lawyer, Gadeir Abbas, addressed the scrum of reporters. “What’s great about being an American citizen traveling abroad is that you have the full power and privilege of the most powerful country in the world at your back,” he said. “But in this situation, it doesn’t look like Gulet had those powers and privileges that are routinely granted to other American citizens.”