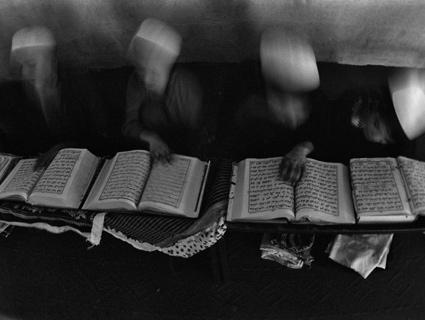

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/wiguardpics/4717768952/">Jackie Guthrie</a>/Flickr

![]() This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

Put what follows in the category of paragraphs no one noticed that should have made the nation’s hair stand on end. This particular paragraph should also have sent chills through the body politic, launched warning flares, and left the people’s representatives in Congress shouting about something other than the debt crisis.

Last weekend, two reliable New York Times reporters, Eric Schmitt and Thom Shanker, had a piece in that paper’s Sunday Review entitled “After 9/11, an Era of Tinker, Tailor, Jihadist, Spy.” Its focus was the latest counterterrorism thinking at the Pentagon: deterrence theory. (Evidently an amalgam of the old Cold War ideas of “containment” and nuclear deterrence wackily reimagined by the boys in the five-sided building for the age of the jihadi.) Schmitt and Shanker’s article was, a note informed the reader, based on research for their forthcoming book, Counterstrike: The Untold Story of America’s Secret Campaign Against Al Qaeda.

And here’s the paragraph, buried in the middle of their piece, that should have stopped readers in their tracks:

Or consider what American computer specialists are doing on the Internet, perhaps terrorist leaders’ greatest safe haven, where they recruit, raise money, and plot future attacks on a global scale. American specialists have become especially proficient at forging the onscreen cyber-trademarks used by Al Qaeda to certify its Web statements, and are posting confusing and contradictory orders, some so virulent that young Muslims dabbling in jihadist philosophy, but on the fence about it, might be driven away.

The italics are mine, and as the authors urge us to do, let’s consider for a moment this tiny, remarkably bizarre window into military reality. As a start, just where those military “computer specialists” are remains unknown. Perhaps they are in the Pentagon, perhaps somewhere in the National Counterterrorism Center, but whoever and wherever they are, here’s the question of the week, possibly of the month or the year: Just what kind of “orders” can they be posting “so virulent that young Muslims dabbling in jihadist philosophy, but on the fence about it, might be driven away”?

And even if our computer experts really were capable of turning wavering young Muslims back from the shores of jihadism—and personally I wouldn’t put my money on the Pentagon’s skills in that realm—what about young Muslims (or older ones for that matter) who weren’t on that fence and took those “orders” seriously? What exactly are they being “ordered” to do?

Talk about a potential Frankenstein situation—and all we can do is ask questions. Just what monsters, for example, might the military’s computer specialists be helping to forge? And who exactly is supervising those “specialists” and their vituperative messages? (Especially since they are unlikely to be in English, and we already know that Arabic, Pashto, Dari, and Farsi speakers at the higher levels, or even lower levels, of the Pentagon are, at best, few and far between.)  Keep in mind that we already have an example of a similarly wacky program lacking meaningful oversight that went awry, hit the headlines, and resulted in the perfectly real deaths of at least one US Border Patrol agent and undoubtedly many more Mexicans. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives launched its now infamous gun-tracking program in Arizona in late 2009, under the moniker “Operation Fast and Furious” (a reference to a series of movies about street car racers). It was meant to track cross-border gun sales to Mexico’s drug cartels by actually letting perfectly real weapons cross the border—more than 2,000 of them, as it turned out. ATF agents, according to a Washington Post report, would be “instructed not to move in and question the [gun runners] but to let the guns go and see where they eventually ended up.” And so they did for more than a year and, not exactly surprisingly, those weapons ended up “on the street” and in the ugliest of hands.

Keep in mind that we already have an example of a similarly wacky program lacking meaningful oversight that went awry, hit the headlines, and resulted in the perfectly real deaths of at least one US Border Patrol agent and undoubtedly many more Mexicans. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives launched its now infamous gun-tracking program in Arizona in late 2009, under the moniker “Operation Fast and Furious” (a reference to a series of movies about street car racers). It was meant to track cross-border gun sales to Mexico’s drug cartels by actually letting perfectly real weapons cross the border—more than 2,000 of them, as it turned out. ATF agents, according to a Washington Post report, would be “instructed not to move in and question the [gun runners] but to let the guns go and see where they eventually ended up.” And so they did for more than a year and, not exactly surprisingly, those weapons ended up “on the street” and in the ugliest of hands.

The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart asked an apt question about the program: “The ATF plan to prevent American guns from being used in Mexican gun violence is to provide Mexican gangs with American guns. If this is the plan that they went with, what plan did we reject?”

Assumedly, the same question could be asked of the military’s online anti-jihadist program, involving as it evidently does messages believed to be too extreme for wavering young Muslims with an interest in the jihadi “philosophy.” Shouldn’t someone start asking whether those Pentagon’s “orders” to jihadis might not turn out to be the online equivalent of so many loose guns?

After all, what are those specialists ordering them to do? And if actual jihadis actually tried to follow those “confusing and contradictory orders,” possibly being confused and contradictory kinds of guys, if they took them seriously and interpreted them in ways not predicted by their putative Pentagon handlers, is there a possibility that anyone could die as a result? And if such messages turn off some prospective jihadis, isn’t it possible that they might turn on others? And could they, for instance, have been ordered to commit confused and contradictory acts that might end up involving Americans?

Really, someone should blow Schmitt and Shanker’s paragraph up to giant size, tack it up somewhere in the Capitol, and call for a congressional investigation. If the ATF could do it, why not the Pentagon? And honestly, is this how Americans want to see their tax dollars spent?

Read the Schmitt and Shanker piece and you’ll get a sense of what Shakespeare might have called the “oerweening pride” rife in the Pentagon when it comes to its ability to put one (or two, or three) over on the jihadist community. So pleased with themselves were officials that they evidently couldn’t help bragging to the two reporters about their skills. The old phrase “too smart for your own good” comes to mind. It’s enough to make you worry, even based on so little information (which the new book from the two reporters may significantly amplify).

And by the way, if you want another unsettling analogy, when it comes to off-the-wall ideas for “deterring” jihadist networks, check out the major record companies and their efforts to deter communities and individuals from illegally downloading music. The Recording Industry Association of America, representing the four major record labels, decided to make a cautionary example of Jammie Thomas-Rasset, a Minnesota mom, by suing her “for illegally downloading and sharing 24 songs on the peer-to-peer file-sharing network Kazaa in 2006.” So far, the organization has dragged her through three trials, getting terrible publicity. Even if they win and leave her in hock for the rest of her life, do you think for one second that they will have made a dent in the world of illegal downloads or deterred anyone? Just ask your kid.

Don’t think deterrence here, think blowback.

Honestly, if Schmitt and Shanker’s claim is accurate, you should be shaking in your boots. And someone on Capitol Hill should be starting to ask some relevant questions, including this one: Could “computer specialists” in the employ of the Pentagon be responsible for your death in a future terrorist attack?

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of The American Way of War: How Bush’s Wars Became Obama’s as well as The End of Victory Culture, runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, The United States of Fear (Haymarket Books), will be published in November. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.