Illustration by Céline Nadeau

As narco-violence continues throughout Mexico, the government in the Gulf Coast state of Veracruz has taken aim on a pair of unlikely provocateurs. The state is currently pursuing terrorism and sabotage charges against a middle-aged math teacher and a local journalist. Their crime? Spreading false information on Twitter.

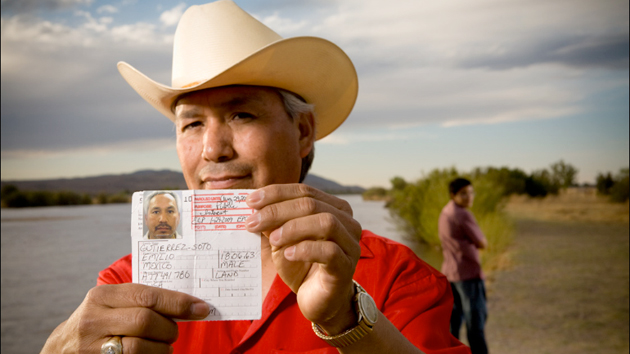

On August 25, rumors spread throughout the port city of Veracruz that there had been an attack at an elementary school in nearby Boca del Río. That’s when teacher Gilberto Martínez Vero (@gilius_22) tweeted, “They took 5 kids, armed group, total psychosis in the zone.” Using the hashtags #Verfollow and #Veracruz, Martínez and reporter María de Jesús Bravo Pagola quickly reached a wide audience of Veracruzanos. Panic ensued as parents raced to pick up their kids and others nearby tried to leave the area, resulting in traffic jams and a number of accidents.

One problem: There was no shooting or kidnapping. After getting in touch with school officials, Veracruz Gov. Javier Duarte de Ochoa attempted to diffuse the situation. By the following afternoon, both Martínez and Bravo had been arrested. Although human rights groups have pushed for their release—the local Amnesty International chapter said the arrest was “unfair and violates their right to justice and freedom of expression”—state officials could push for the maximum 30-year sentence on Martínez and Bravo. On top of that, the state is investigating 15 other people who tweeted similar information during the chaos.

This isn’t the first time that Mexican officials have seen Twitter as problematic; as Jen Quraishi wrote for MoJo last year, the federal government was considering banning the service (along with Facebook) so drug cartels couldn’t use it to communicate with each other. But the Veracruz case can be seen as the result of a different effect of the drug war: the intimidation and silencing of journalists throughout the country.

As Daniel Hernandez wrote in the Los Angeles Times:

The case also underscores what can happen when traditional media censor themselves to avoid the ire of the drug gangs, leaving a frightened public to search for vital information from other sources.

As drug-related fighting has increased in Veracruz in recent months, attorney Fidel Ordonez argued, more citizens are turning to Twitter and Facebook to update one another on violent incidents. Social networking often fills a void left by largely silenced local news media, he said.

Tim Johnson, who has written about Mexican social-media use as McClatchy’s Mexico City bureau chief, had this to say last week: “Many Mexicans there feel conventional media no longer provide quick, reliable information because gangsters have terrorized or co-opted journalists. So citizens have turned to social networks. Twitter is full of Mexicans tweeting about the security situation in their cities.”

It’s unlikely that the violence will end any time soon in a country the Committee to Protect Journalists calls one of the most dangerous in the world. Just last week, two more reporters were found murdered in the capital, bringing the number of Mexican journalists killed since President Felipe Calderón’s proclamation of war on the cartels in 2006 to at least 59. Calderón’s tactics may have made for good press five years ago, but these days, it’s hard to find anyone willing to cover the mess that has ensued.