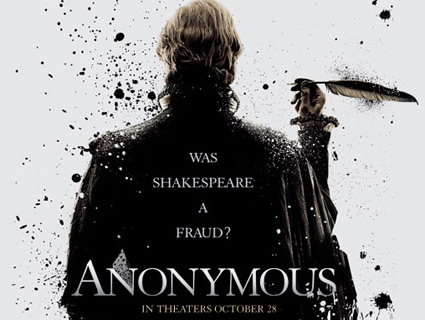

No. No, he was not.Screenshot: <a href="http://anonymous-movie.com/">anonymous-movie.com/</a>

Anonymous

COLUMBIA PICTURES

130 minutes

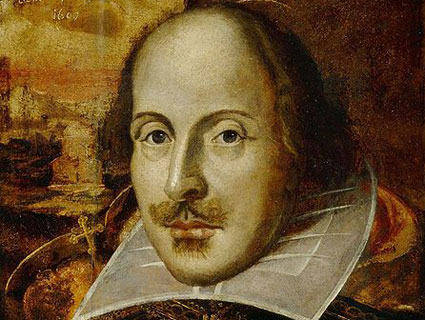

Did you know that lionized playwright William Shakespeare was a humongous pansy of a fraud? How about that he was illiterate? Or that he didn’t write even a single letter of any of the comedies, tragedies, or sonnets commonly attributed to his name? No need to sweat your ignorance. These are facts of which I was not aware, either. I also wasn’t aware of the fact that such tiresome theories could be distilled into a movie as drab, half-baked, and scandalously bad as Anonymous.

You might’ve heard about the film by now: It takes place during the sanguinary twilight of England’s Elizabethan era, in an underworld where staged drama is just another tool for protest and social upheaval. The script posits that Shakespeare was a crass, opportunistic phony; in Anonymous, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was the true author of the plays, and Shakespeare contemporary Ben Jonson was de Vere’s inept middleman. The earl uses his plays to make political statements to the low-born masses (“Words will prevail…not swords,” de Vere proclaims mightily) but, fearing reprisal, opts out of taking credit.

Needless to say, Anonymous—which managed to generate Oscar buzz that lasted for about eight seconds—has difficulty accepting widely corroborated historical facts. But let’s pretend for a moment that none of that matters and observe the film purely on its artistic merits.

Verdict: In a year that saw the theatrical release of Something Borrowed and Dream House, Anonymous still claims the mantle of sorriest cinematic act of 2011.

Anonymous combines stodgy writing, lackluster direction, lame flashbacks, muddled politics, and wooden acting into one colossal misuse of time. Tales of repression, trailblazing stagecraft, incest, and murder are weaved together so clumsily that it’s impossible to give a damn about the cosmetically juicy details.

Seventeenth-century London is recreated with adequate pomp and flash, but the emotional core and intellectual hunger required to keep such a far-fetched story afloat are altogether absent. When potentially gripping elements of political intrigue are introduced—involving armed rebellion, attempted assassination, and succession to the throne—the subplots play out as disposable, petty squabbles. When a crucial plot twist is unveiled, the shock value is dulled by lack of consequence. And when rebels are beheaded, and a rioting proletariat is mowed down in the cobblestone streets of London, the climactic events have the visceral and emotional impact of a cut scene from a bad video game.

Most egregiously, the film never attempts to explore the complex creative process behind de Vere’s alleged oeuvre, instead relying on brooding atmosphere and a provocative conspiracy theory to make up the difference. In absurd scenes depicting the birth and development of his genius (apparently de Vere wrote A Midsummer Night’s Dream at an age when he should’ve been watching Power Rangers), his craft is treated as if it were somehow a digression from the central plot. The audience is thus left with the thoroughly unsatisfying explanation that de Vere was rich, sophisticated, well educated, and tremendously gifted, and that we should just deal with it.

The acting doesn’t help, either. British actor Sebastian Armesto plays Ben Jonson with the aplomb of an NFL towel boy; judging from this effort, you’d never suspect Jonson of being one of the most celebrated dramatists of the era (the movie goes as far as to label him as having “no voice” as a writer). Numerous royal figures and noblemen are portrayed with all the gravitas found in an episode of The Real Housewives of New Jersey. The occasional talent is shamefully squandered. The wonderful Vanessa Redgrave, playing Queen Elizabeth I, is reduced to a glorified prop in most of her scenes, and in the moments when she finally gets to emote, she’s hobbled by the script’s dialogue-to-nowhere. And Rhys Ifans (who played Hugh Grant’s dim-witted roommate Spike in the 1999 rom-com Notting Hill, and Ivan, a disillusioned musician, in Noah Baumbach’s 2010 dramedy Greenberg) disappears into the role of de Vere, making a valiant effort to escape a fundamentally uninteresting role.

Now, back to the issue of historical veracity: There’s a glut of wacky “alternative” theories out there aimed at debunking well-established historical narratives. Often times, they get dusted off and granted false legitimacy by excitable Hollywood executives—take Oliver Stone’s JFK and the Hughes brothers’ From Hell, for instance. But in the case of JFK, skillful filmmaking and taut storytelling allowed viewers to gladly suspend skepticism for three-and-a-half hours, and From Hell didn’t take itself particularly seriously. Anonymous possesses none of these redeeming qualities. Instead, the film comes across as a sincere effort to change the course of an academic debate.

Anonymous practically begs the viewer to take it seriously. But fringe theories on Shakespeare authorship (and there’s a hell of a lot of them) have encountered nearly universal rejection and scorn among those who’ve dedicated their lives to studying the Bard and the folios.

“The Oxfordian theory is utter nonsense,” says Katherine Attie, a professor at American University specializing in early modern British literature and culture. “[The claims amount] to simple snobbery: The elitist notion that a middle-class provincial without a university education couldn’t possibly have written these plays. In the case of Edward de Vere, the silliness of that idea should be apparent to anyone who bothers to check the facts. But people like mysteries, and conspiracy theories are intriguing.”

The evidence is gratuitously, crushingly, fantastically, overwhelmingly clear that William Shakespeare was, in fact, William Shakespeare. When you’re aiming to take down evidence that solid, it might be smart to have someone other than Roland Emmerich at the helm. Emmerich is also responsible for historically sound masterworks like the Mel Gibson vehicle The Patriot and this tour de force:

Ultimately, what really tanks Anonymous is its inability to convince the audience to care. If you’re going to make a film that flips such an enormous middle finger to every lit major and drama teacher who has ever lived, the least you could do is make it entertaining.

Anonymous gets a wide release on Friday, October 28.