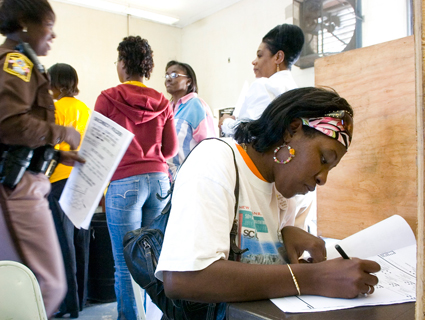

A voter receives a sticker after casting her ballot in the South Carolina Democratic Presidential Primary at the Turner Memorial A.M.E. Church in West Columbia, South Carolina, in 2008.Erik S. Lesser/Zuma

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before, maybe from Glenn Beck or on RedState: Election fraud is rampant, a vile, corrupting force that’s decimating the integrity of the American electoral system. It’s a widely propagated conservative myth, one that’s been used by Republicans around the country to justify new laws requiring voters to obtain IDs in order to cast a ballot.

Critics say that these laws have historically affected minority voters disproportionately. As Adam Serwer wrote back in September, Republican defenders of voter ID laws point to higher black turnout in Georgia during the 2006 and 2010 elections as evidence that such laws don’t suppress the minority vote. But in states without such restrictions, the increase in black turnout was much higher.

Under South Carolina’s new law, passed in August, prospective voters must present either a valid driver’s license or ID card, military ID, or passport. Absent of any of those, people may still cast absentee or provisional ballots. But, under the state’s new law, these ballot-casters must eventually produce a valid ID. And though South Carolina is offering free IDs, voters still have to present identification documents—like a birth certificate or marriage record—in order to obtain one.

Previously, South Carolina election officials reported that the law impacts white and non-white voters proportionally—meaning that no group would be worse off because of the law. But the AP analyzed fresh data provided by the South Carolina state election commission. Its findings are unsurprising:

[A]mong the state’s 2,134 precincts, there are 10 where nearly all of the law’s affect falls on nonwhite voters who don’t have a state- issued driver’s license or ID card, a total of 1,977 voters.

The same holds true for white voters in a number of precincts, but the overall effect is much more spread out and involves fewer total voters: There are 44 precincts where only white voters are affected, or 1,831 people in all.

The precinct that votes at Benedict College’s campus center has 2,790 voters, including nine white voters. In that precinct, 1,343 of the precinct’s nonwhite voters lack state identification, but only five white voters do. The former group accounts for 48 percent of the precinct’s voters…

A precinct at South Carolina State University has 2,305 active voters, including 33 white voters. There, 800 nonwhite voters and 17 white voters there lack state IDs. More than a third of the voters in the precinct lack state photo identification.

Section Five of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) requires jurisdictions that once used a “test or device” to bar people from voting (like a literacy test or poll tax), and had a turnout below 50 percent in the presidential election of 1964, to clear any changes to their election laws with the Department of Justice. Thanks to its long, storied history of voter disenfranchisement, South Carolina is one of sixteen states that must clear at least some of its election law changes with the DOJ. The DOJ is still reviewing the state’s voter ID law to see if it violates the VRA, and has asked the state to clarify how it intends to reach out to voters without valid IDs.

These past few months, Republicans around the country have been waging war against the Voting Rights Act. Republican officials in Alabama, Arizona, and Texas, for example, are locked in battle with the DOJ over redistricting changes that dilute the strength of minority voters. Granted, these suits challenge different aspects of the VRA. But taken as a whole, they suggest that the GOP is eager to test the DOJ’s enforcement of the law early and often.