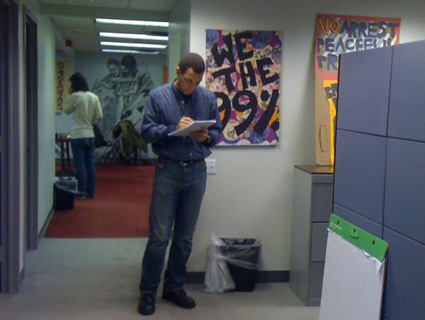

The main hallway of "the Occupied office" <a href="https://twitter.com/?photo_id=1#!/OccupyWallStNYC/status/136858484858826752/photo/1">@OccupyWallStNYC/Twitter

Near the top of an office building at a secret address on Broadway in Lower Manhattan there’s a door hung with a yellow placard, reading, “This is a good sign.” Open that door and you’ll meet a man sitting at a folding table behind a Toshiba netbook. He’s Occupy Wall Street’s doorman. If somebody is expecting you, or if you’re in his database of verified working-group members, he’ll let you inside. And then you’ll be in the closest thing the Occupy movement has to a new headquarters.

“It’s obviously kind of a hub where information flows though,” Nathan Stueve, a member of OWS’ press team, tells me. Like everyone else in the office, he wears a numbered tag that says, “The Occupied Office.” Stueve explains that there are 48 of these tags, corresponding to the space’s fire capacity—the tags are a way of making sure that the activist hive doesn’t run afoul of building management.

Details about the Occupied office are hard to come by, a reflection of the movement’s post-eviction shift from radical transparency into something more akin to stealth mode. Stueve, who has been with OWS for only three weeks, says he learned of the office’s existence a few days before last Tuesday’s Zuccotti Park eviction. He says he doesn’t know when it first opened or who’s paying the rent.

A member of the OWS Workspace Affinity Group, which oversees the space, declined to give me a tour or answer questions about it. Some organizers worry the place has already attracted too much attention. “This is a space in progress,” notes a handwritten sign just inside the door, adding that it is meant for projects that require power, internet, and telephone lines. “We are working as quickly as possible to open up the space to as many working groups as possible in a way that offers an open, productive, effective space for all.”

Among other things, the office houses OWS’ press and media teams, the Finance Working Group—which dispenses small amounts of cash to occupiers who show up with receipts—and other working groups such as Internet, Open Source, and Technology.

It’s hardly the movement’s only workspace. The Spokes Council, the movement’s quasi-governing body, held it’s latest meeting at a Times Square auditorium owned by a local chapter of the Service Employees International Union. Students at Manhattan’s New School have occupied a classroom that they are using for teach-ins. Two Manhattan churches have opened their doors to the camp’s homeless. And meetings continue at the park, in the nearby atrium of 60 Wall Street, and in other spaces owned by religious and labor groups. The Center for Constitutional Rights will soon roll out an online listing service to connect occupiers with other groups that can offer free space.

But for a movement that now lacks a single center of gravity, the Occupied Office is playing an increasingly important role. “This space definitely fills a need right now,” Stueve says. As we talk, a stream of occupiers goes in and out, passing a framed silk-screened print of an African American woman emblazoned with the “We are the 99%” slogan. On another wall is a cluttered dry-erase “Info” board asking, “Know someone with a truck?”

The office, unlike Zuccotti Park, is carefully guarded against people who might try to do the movement harm. The netbook guy, Stueve explained, checks to make sure that only authorized people get past the door, “and not thieves or provocateurs or whoever else might try to come up here.”

It’s certainly a much easier place to work than the park. Office rules require that all cellphones stay on vibrate mode, people talk in low voices, and any larger meetings take place in the hall outside.

Before I leave, a young girl in a nose ring signs in with the doorman. “Will you be staying for a while?” he asks.

“I’m going to be working all night long,” she says.