Doran/FlickrOn Thursday evening, residents of 83 towns and cities throughout the country—places like Marietta, Georgia, and East Troy, Wisconsin, and Anchorage, Alaska—will make their way to the home of a friend or neighbor or outright stranger for a night of partying. But these aren’t holiday parties. They’re the ground-level rumblings of a growing campaign to roll back one of the most game-changing Supreme Court decisions in recent memory, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Doran/FlickrOn Thursday evening, residents of 83 towns and cities throughout the country—places like Marietta, Georgia, and East Troy, Wisconsin, and Anchorage, Alaska—will make their way to the home of a friend or neighbor or outright stranger for a night of partying. But these aren’t holiday parties. They’re the ground-level rumblings of a growing campaign to roll back one of the most game-changing Supreme Court decisions in recent memory, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

In a year packed with populist uprisings, in which Time named “the protester” its person of the year, the fight against Citizens United is gaining momentum with battle fronts in Congress, statehouses, city halls, and the homes of hundreds of Americans. The decision, handed down in January 2010 by the court’s five conservative justices, effectively gave corporations the same free speech rights as people, gutted key provisions of the 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, and green-lighted unlimited spending by corporations and labor unions in American elections. Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, a pro-reform campaign finance organization, called it “the most radical and destructive campaign finance decision in Supreme Court history.”

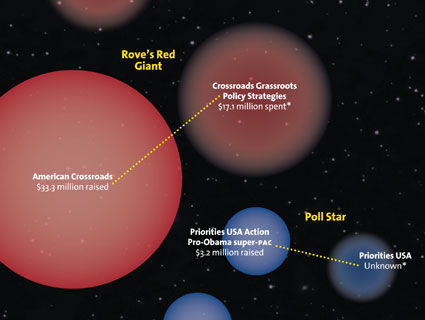

The campaign to counter Citizens United sprang to life immediately after the ruling was announced. Led by Public Citizen, the good government group founded by Ralph Nader, its goal is to pass a constitutional amendment that neutralizes the ruling’s effects. But the effort didn’t fully take off until this year—the public needed time to see what the decision had wrought. To influence the 2010 midterm elections, super-PACs and other independent spending outfits that sprung in the wake of Citizens United spent hundreds of millions of dollars.

This past March, Public Citizen launched a website called Democracy Is for People. It urges people to sign a petition supporting a constitutional amendment, offers a primer on Citizens United‘s impact, and helps people organize house parties to build support for the idea of an amendment. (More than 300 parties have been hosted to date, the group says.) Also behind the campaign are Common Cause, Move to Amend, and People for the American Way, groups that have been circulating online petitions, writing sample resolutions rebuking Citizens United, and training activists.

Amending the Constitution, of course, is no small matter: At least two-thirds of each house of the Legislature must approve the amendment, and then at least three-quarters of the state legislatures must ratify it. Many observers doubt that a Citizens United amendment stands a chance. In the 235 years of the republic, after all, there have been 11,372 attempts to amend the Constitution. Only 27 succeeded. That’s a success rate of 0.2 percent.

Elizabeth Wydra, chief counsel for the Constitutional Accountability Center, a progressive think tank, wrote in January that while an amendment is one option for progressives in overturning Citizens United, it’s important to remember that amendments are seen as a way to correct flaws in the Constitution itself.* Citizens United is not a constitutional flaw, though; it’s a flawed interpretation. Those seeking to neutralize it, she argued, should also advocate for judicial nominees who share their distaste for corporate personhood and influence-peddling.

Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, acknowledges the skeptics but insists there are few other feasible options. The closest the reformers have come to blunting the impact of Citizens United was the DISCLOSE Act, a bill intended to beef up disclosure of donors who fund campaign advertising—it died in the Senate last year in the face of united Republican opposition. “The challenge is overcoming that skepticism about the amendment,” Weissman says. “The only way to do that is to build a movement.”

And now’s the time to start, according to those involved. The drive to get special-interest money out of American politics dovetails with the ethos of Occupy protests throughout the country, says Mary Boyle, a spokeswoman for Common Cause. “Obviously, one of Occupy’s big concerns is that our political system is broken and it’s not serving people,” she says, “and we’re certainly hopeful that this will resonate with people who will feel that way.”

There are currently at least four resolutions in the House of Representatives seeking a constitutional amendment to counteract Citizens United. In the Senate, Tom Udall (D-N.M.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) have introduced their own amendments, which specifically give Congress and state legislatures more power to write new laws stanching the flow of political cash. Both say the Senate will likely take up their bills next year.

Udall told me he’s constantly talking with Republican colleagues about money in politics, and he hopes to get some GOP support for his bill, whose cosponsors now consist of 16 Democrats, plus Sanders. He points to Congress’ 11 percent approval rating and multiple surveys showing widespread support for such an amendment and for a general crackdown on corporate influence in politics. “This is a chance for Congress to redeem itself,” Udall says.

While Udall twists arms in Washington, city and governments nationwide have been weighing in. Last week, prodded by Move to Amend, Los Angeles became the first major city to pass a resolution urging Congress to amend the Constitution to revoke the corporate personhood rights the justices laid out in Citizens United. Move to Amend hopes to get an anti-Citizens United measure on the ballot in 50 towns and cities for the November 2012 elections—already, it reports, resolutions or ballot measures opposing corporate personhood have been proposed or passed by 36 local governments.

Legislators in nine states have also offered and/or passed similar statewide resolutions. Last week, Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley urged legislative leaders to speed passage of a state resolution that would “put the electoral process back in the hands of the people, not corporations.”

On a conference call Tuesday, Derek Cressman, who’s spearheading the effort for Common Cause, told fellow activists that plans were underway to introduce statewide ballot measures. The 17th Amendment, allowing for direct election of US senators, was passed, Cressman pointed out, by building local and statewide support through propositions and measures. (It’s also a strategy conservative groups have used effectively to pass state anti-abortion measures.)

Cressman stressed that while amending the Constitution is the most ambitious policy option in the book, the sheer amount of money pouring into elections combined with dwindling disclosure requirements called for drastic action. “This does feel like a rare moment in history—a constitutional moment if you will—when the American people are saying we need to focus our attention on this and get it right,” he said.

Citizens United, Udall concurs, “has made it so we need a constitutional amendment. I don’t see how we tackle this any other way.”

This paragraph has been clarified to better reflect Wydra’s views on the Citizens United constitutional amendment campaign.