On Friday, day three of Susan G. Komen’s mission/PR clusterf*ck, the group announced it was reversing its decision to defund Planned Parenthood. Well, sort of. What Komen reversed was the claim that PPFA had been blackballed because it was under investigation. The question of PPFA getting further funding is left open until the next grant cycle. Can meet road.

This non-reversal reversal was just the latest example of terrible crisis communications that compounded what was a mind-blowingly stupid decision to begin with. How did Komen come to such a terrible decision? (Hint.) Once made, why did they let Planned Parenthood frame it? Why did they wait almost two full days after the story broke—meanwhile hemorrhaging advisory board members, chapters, corporate sponsors, donors, and enduring poignant disappointment at the hands of Andrea Mitchell and Judy Blume fer Christ’s sake—before even attempting to control the damage?

These mysteries have all been much pondered, and I won’t do so here again. The question now before Komen is: Can it regain the trust of all those women and men who ran 5Ks and bought boatloads of pink stuff in the belief that this was the best way to ensure breast cancer research, screenings, and treatment?

The answer to that question, as to all the previous ones, lies with the board.

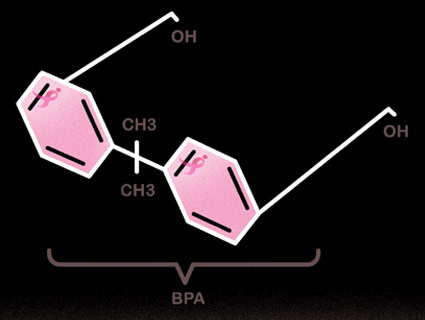

Source: Susan G. Komen 2009-2010 Annual ReportLet me stipulate: I’ve long had mixed feelings about Komen. Years ago, I edited Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Welcome to Cancerland,” so I was well versed in “pinkwashing,” i.e. corporations donating a miniscule fraction of money earned from peddling stuff adorned with Komen’s pink ribbon to cancer research, or holding a run (after which less than half of the proceeds go to “the cause,” pre-overhead) rather than, say, providing decent health care to workers or keeping toxins out of water supply. I was also aware that Komen had threatened to sue other charities for daring to use “for the cure” in their marketing. That Komen had denied the link between BPA and cancer (while taking in lots of money from BPA makers and users) and generally prioritized “treatment” and “the cure” over “prevention.” But hey, Komen did “raise awareness,” and when you’re talking about a disease that afflicts 1 out of every 8 American women, maybe you take the good with the bad, right?

Source: Susan G. Komen 2009-2010 Annual ReportLet me stipulate: I’ve long had mixed feelings about Komen. Years ago, I edited Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Welcome to Cancerland,” so I was well versed in “pinkwashing,” i.e. corporations donating a miniscule fraction of money earned from peddling stuff adorned with Komen’s pink ribbon to cancer research, or holding a run (after which less than half of the proceeds go to “the cause,” pre-overhead) rather than, say, providing decent health care to workers or keeping toxins out of water supply. I was also aware that Komen had threatened to sue other charities for daring to use “for the cure” in their marketing. That Komen had denied the link between BPA and cancer (while taking in lots of money from BPA makers and users) and generally prioritized “treatment” and “the cure” over “prevention.” But hey, Komen did “raise awareness,” and when you’re talking about a disease that afflicts 1 out of every 8 American women, maybe you take the good with the bad, right?

I knew too that the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure™ had purposefully strived for a nonpartisan image (despite the fact that founder/CEO Nancy Brinker was a major Bush funder and ambassador) and that part of that was staying on the sidelines about issues of choice. A perfectly reasonable course.

But the board abandoned neutrality when, as part of a larger attack on Planned Parenthood that began with the antics of conservative pseudo-journalist James O’Keefe, pro-life groups began targeting Komen for their Planned Parenthood grants. They were assisted from the inside by new Senior VP for Public Policy Karen Handel, who’d recently run for governor of Georgia on a pro-life and stridently anti-Planned Parenthood platform, and further guided by Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer*. [Update: Handel finally fell on her sword and resigned on Feb. 7.]

But all attention that’s been paid to the Handel/Fleischer deus ex machina, however, misses the greater culprit: a sucky board.

What do I mean?

The board of directors (not to be confused with Komen’s multitudinous advisory boards) currently has nine members. There’s Nancy Brinker, who founded Susan G. Komen in the name of her sister, who died of breast cancer. Brinker is a major mover and shaker in Dallas GOP circles, and a former major bundler, a.k.a. “Pioneer,” for George W. Bush. Also on the board is Brinker’s son Eric. Then there’s Dallas socialite/philanthropist/GOP donor/oil baroness/Junior Leaguer Linda Custard, who chairs the board of the elite Hockaday prep school (once attended by G.W. Bush’s daughters), and serves as a trustee for Southern Methodist University (eventual home to the G.W. Bush Library). Connie O’Neill has a similar portfolio; she notably serves on the school district finance committee of the uber tony Highland Park (the most enthusiastically conservative zip code in the country), as well as the Crystal Charity ball, which is ne plus ultra in the world of rich Texas Republicans (and where O’Neill was coincidentally named one of Dallas’ ten best dressed women). Also in the rich Republicans camp is corporate real estate law firm founder (and Silicon Valley VC) Linda Law, who’s a Republican National Committee Regent, meaning a $250,000+ donor.

But wait, there are a few Democrats, including former Nine West executive Brenda Lauderback, who made some modest donations to Obama but is also notable for the number of boards she serves on (Bloomberg Businessweek links her to 51 board members in five different organizations across six different industries). Fellow Obama donor, oncologist Dr. LaSalle D. Leffall Jr., is co-chair of the board, and the only medical professional on it. A bigger Dem donor is lobbyist John D. Raffaelli, whose firm Capital Counsel LLC helps both GOP and Dem causes; he was also the counsel for tax and international trade to former Sen. Lloyd Bentsen (D-Tex.). Finally there’s the only board member without any track record of political donation: breast cancer survivor, longtime Komen foot soldier, and VP at a hospital consulting service, Elyse Gellerman, whose job is to represent the Komen affiliates.

But my point isn’t about who’s a Republican and who’s a Democrat. The point is that Komen is a giant grant-making operation (nearly $2 billion since 1982) that purports to represent all of womanhood and it’s being run as if it were still a small family foundation. Brinker and son, Custard, and O’Neill all run in the same circles, sit on the same boards, send their kids to the same elite schools. Komen’s board makes a nod to race (both Lauderback and Leffal are African-American), a nod to medicine, and a nod to someone with pull in DNC circles, but the core is a group of rich, Texan, conservative friends.

There should be more racial and economic and regional diversity, to be sure. But Komen should, and must now if it wants to regain trust, bring on board members who will challenge the way Komen has done business. Like downplaying environmental factors that would be problematic for corporate sponsors. Like being less than honest with runners and ribbon-buyers about how little of the money raised in those events actually goes to research or treatment.

Board members don’t run the day-to-day operations, but they should be (and were) consulted on controversial decisions and they do step in when an organization is in crisis. It’s not likely, but the board’s best move would be to reform itself. Enlist people like Ehrenreich, tech-goddess Xeni Jardin (who’s been chronicling her fight with breast cancer), and Dr. Susan Love, a leading researcher who’s been critical of Komen’s lack of effort toward prevention. Andrea Mitchell wouldn’t hurt either. If you can’t or won’t put them on the board, make sure you somehow capture their POVs.

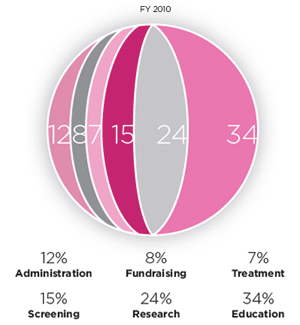

New energy might, for example, persuade the board that it’s time to change the balance between money spent on treatment (7%), screening (15%), research (24%), and “education” (34%). Two decades ago, it was of utmost importance to get women to get over the fear and the shame and into the doctor’s office, to go public with scars and wigs and hot flashes. But mission accomplished, Komen. Now it’s time to put more weight into stopping the disease before it starts. Dig deep enough into Komen’s financial statements, and you’ll find that of the 24 percent they spend on research, only 15 percent goes to explore how to prevent the disease. Pharmaceutical companies probably do a pretty good job of finding new and better chemo drugs; a nonprofit should put more of its clout into research without a near-term financial payoff.

New insight might also help the board to grok that if they want to maintain a fig leaf of impartiality in the abortion debate and they bring on Jane Abraham—head of the Susan B. Anthony List; the most powerful pro-life funding group around—to their “advocacy alliance” board, they’d better enlist someone like Stephanie Schriock of pro-choice group Emily’s List as a countermeasure. And a board more savvy to opinions outside of Highland Park might persuade Brinker she should sit back on her Neiman Marcus/Chili’s fortune and not pay herself $417,000 a year plus board-approved first-class travel from the donations of jogging bald ladies and their family members.

And for god’s sake, get a better crisis communications team. Or at least a head of communications that has more than 154 followers on Twitter.

*This article has been corrected to reflect the fact that Fleischer advised on hiring of other Komen VPs, not Handel.